EUROCONTROL

EAPPRI V3.0 – Released Issue

European Action Plan for the

Prevention of Runway Incursions

EUROCONTROL

Edition Number: 1.0

Edition Validity Date: 20/11/2017

2

3

Statement of commitment .................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................... 04

Introduction and background

......................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................... 07

What's changed

...................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................... 08

Important and urgent action

............................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................ 10

European Action Plan for the Prevention of Runway Incursions

Recommendations ............................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................. 13

1.1 General principles

................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................... 14

1.2 Aerodrome operator issues

....................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................... 16

1.3 Communications

...................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................... 20

1.4 Aircraft operator issues

..................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................... 21

1.5 Air navigation service provider issues

......................................................................................................................................................................................................................................... 23

1.6 Data collection and lesson sharing

................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................. 27

1.7 Regulatory issues

..................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................... 28

1.8 Aeronautical information management

.................................................................................................................................................................................................................................. 30

1.9 Technology

....................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................... 31

1.10 Civil military

.................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................... 32

2.0 Future work

...................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................... 34

Appendices

................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................... 36

A Communications guidance

........................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................ 37

B Guidelines for aerodrome local runway safety teams

............................................................................................................................................................................................ 48

C Airside vehicle driver training

................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................. 58

D Aircraft operator / Flight crew best practices

.................................................................................................................................................................................................................... 70

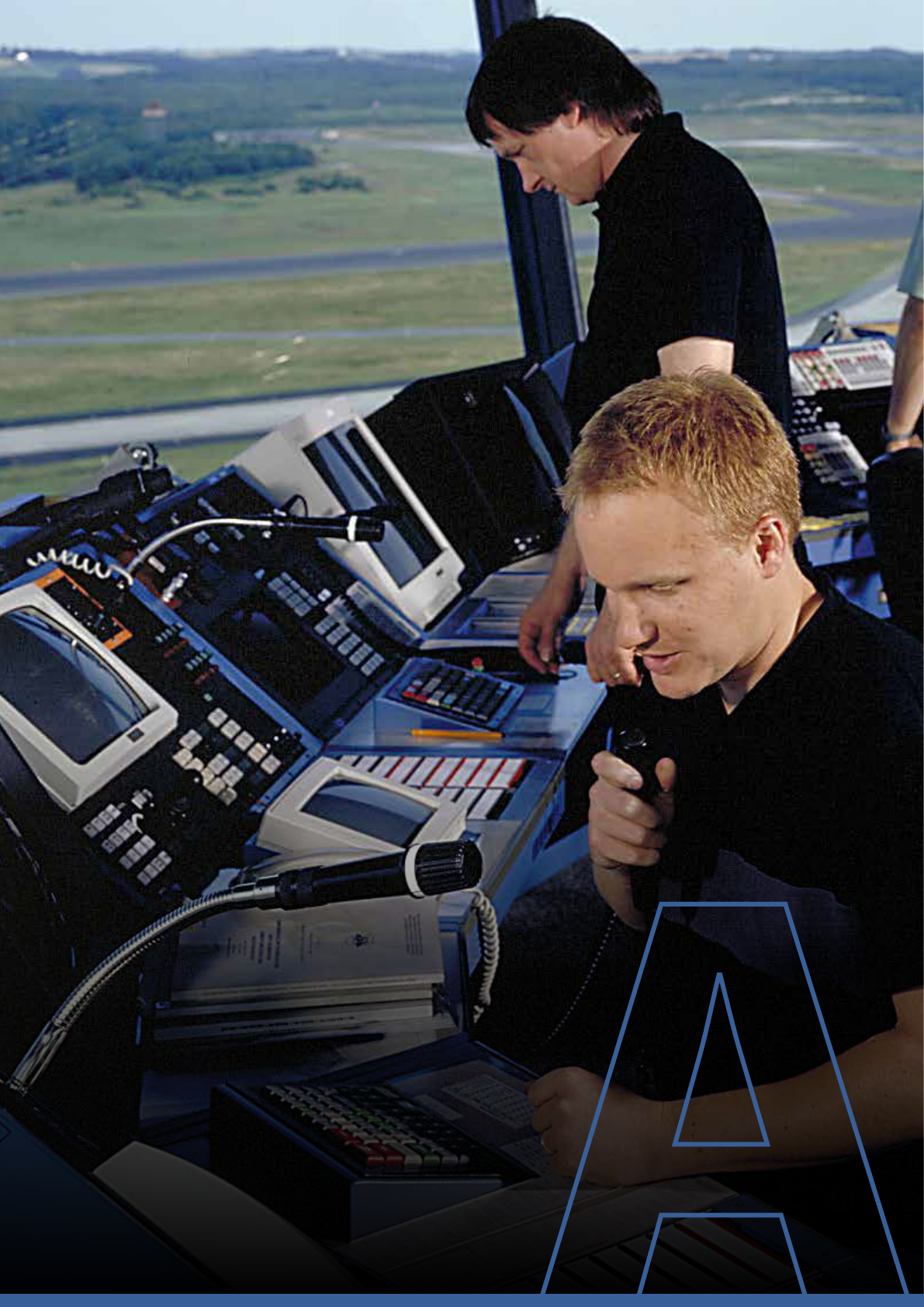

E Air navigation service providers / Air traffic controller best practices

............................................................................................................................................. 80

F Oversight activities for regulators

..................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................... 92

G Safety management systems

.................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................. 96

H Aeronautical information management guidance

.................................................................................................................................................................................................100

I Guidance for joint use aerodromes Civil-Military

.................................................................................................................................................................................................108

J Use of aeronautical ground lighting that protects the runway

.............................................................................................................................................................114

K Aerodromes design guidance for the prevention of runway incursion

......................................................................................................................................120

L Maintenance, inspections, works in progress/temporary modifications of the aerodrome

..........................................................................126

M Technology

.................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................... 132

N Interpreting events – Runway incursion?

............................................................................................................................................................................................................................138

O Bibliography

................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................146

CONTENTS

4

The rate and numbers of runway incursion reports remain steady.

From the reports and data that are received, it is shown that

there continue to be a minimum of two runway incursions every

day in the European region. Accidents continue to take place

on runways. Findings from those incident and accident reports

have been used to determine the new recommendations and

associated guidance materials contained in this update to the

European Action Plan for the Prevention of Runway Incursions

(EAPPRI).

The increasing availability of runway incursion incident reports

is a positive indication of the commitment of organisations

and operational staff to prevent runway incursions and runway

accidents by learning from the past accidents and incidents and

sharing this information across Europe.

The establishment of aerodrome local Runway Safety Teams

(RST), which should comprise, as a minimum, representatives

from Aircraft Operators, Air Navigation Service Providers and

the Aerodrome Operator, is helping to facilitate effective local

implementation of the recommendations. At the same time,

aerodrome local Runway Safety Teams address runway safety

specific issues relating to their own aerodrome.

Core to the new (and existing) recommendations contained

in this document is the uniform and consistent application of

ICAO and, increasingly, EU provisions. It is for the Regulator/

National Aviation Authority to decide upon the strategy for

implementation at applicable aerodromes within its own State.

The recommendations are mainly generic and it will be for the

responsible organisations to decide specific details, after taking

local conditions into account e.g. aerodromes where joint civilian

and military operations take place.

The new recommendations are the result of the combined

and sustained efforts of organisations representing all areas of

aerodrome operations. The organisations that contributed to

this action plan are totally committed to enhancing the safety

of runway operations by advocating the implementation of the

recommendations that it contains. These organisations include,

but are not limited to, Aerodrome Operators, Air Navigation

Service Providers, Aircraft Operators, and Regulators/National

Aviation Authorities.

STATEMENT OF COMMITMENT

5

The following organisations and persons have actively contributed to the review of EAPPRI Edition 2.0 and the production

of this EAPPRI Version 3.0.

ORGANISATIONS AND LIST OF ACTIVE

PARTICIPANTS INVOLVED IN THE PRODUCTION

OF EAPPRI VERSION 3.0

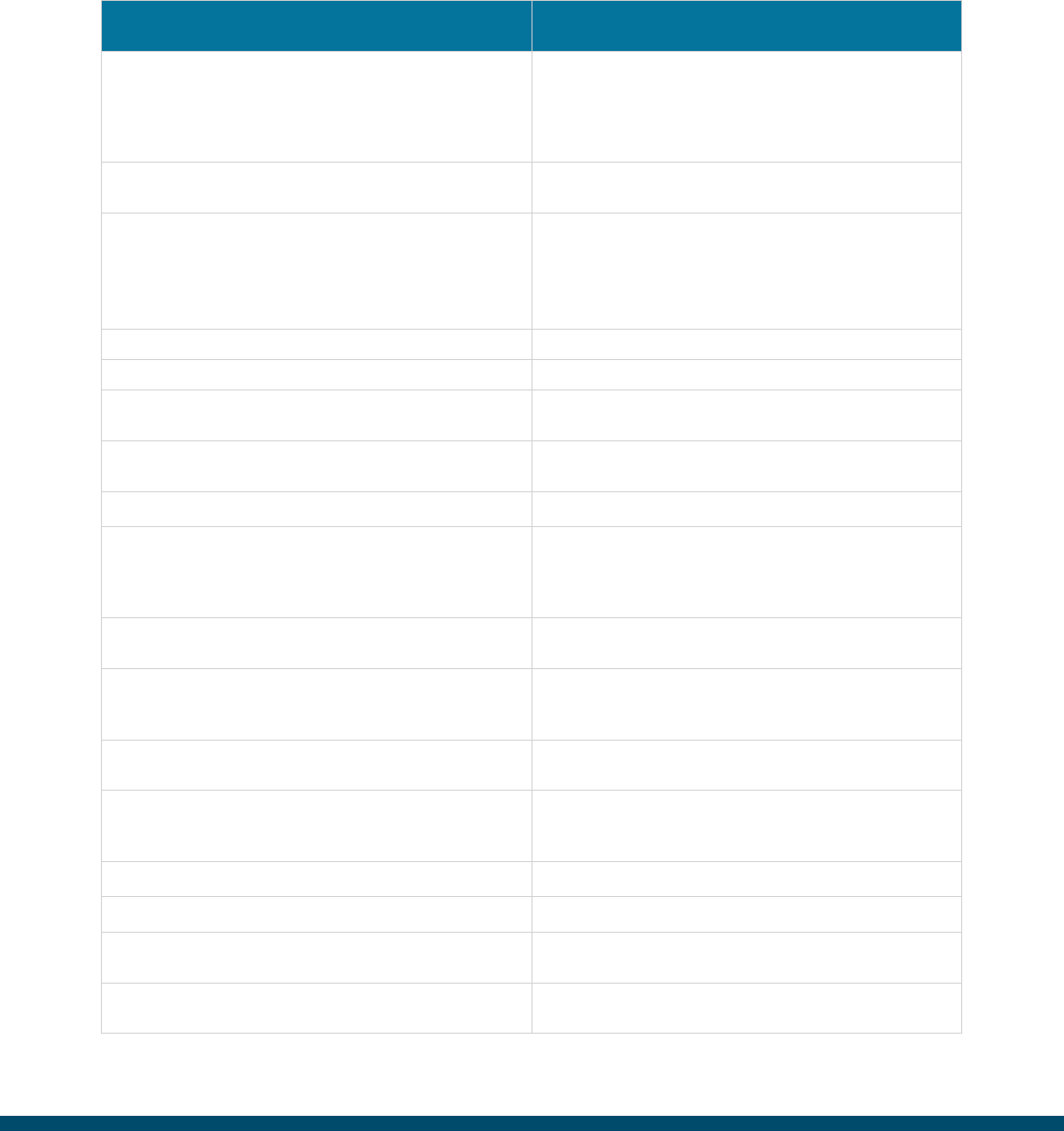

ORGANISATION CONTRIBUTOR

EUROCONTROL NETWORK MANAGER • Richard “Sid” Lawrence: EAPPRI v3.0 Development Lead

• Tzvetomir Blajev

• Asa Standar

• Goran Redzepovic

• Francisco Hoyas

AIRPORTS COUNCIL INTERNATIONAL ACI EUROPE • Ian Witter (London Heathrow Airport)

• Dirk Geukens (Brussels Airport)

EUROPEAN COCKPIT ASSOCIATION ECA • Loic Michel

• Captain Johan Glantz

• Captain Peter Drichel (Vereinigung Cockpit (VC))

• Captain Peter Rix (Vereinigung Cockpit (VC))

• Captain Moritz Burger (Vereinigung Cockpit (VC))

EUROPEAN REGIONAL AIRLINES ASSOCIATION ERAA • Captain Pascal Kremer (Luxair)

INTERNATIONAL CIVIL AVIATION ORGANISATION ICAO • Brian de Couto

INTERNATIONAL AIR TRANSPORT ASSOCIATION IATA • Anthony van der Veldt

• Stefano Prola

RYANAIR • Captain Andrew Elbert

• Captain Juan de la Roca

EASYJET • Captain Peter Malady

BELGOCONTROL • Xavier Belles

• Marc Evens

• Luigi Locoge

• Patrick Persoons

ENAIRe • Alfonso Barba

• Alberto Rodriguez de la Flor

ENAV S.P.A. • Maria Grazia Bechere

• Felice De Lucia

• Stefano Romano

DEUTSCHE FLUGSICHERUNG DFS • Martin Peters

• Martin Rulffs

DIRECTION DES SERVICES DE LA NAVIGATION AÉRIENNE

DSNA

• Pierre-Francois Dinelli

• Sebastien Raphoz

• Yan Le Fablec

FerroNATS • Raquel Martinez Arnaiz

FINAVIA • Paavo Puranen

KONTROLA ZRANCNEGA PROMETA SLOVENIJE

SLOVENIA CONTROL

• Robert Segula

LFV AIR NAVIGATION SERVICES OF SWEDEN • Erik Wildenstam

• Maria Lundahl

6

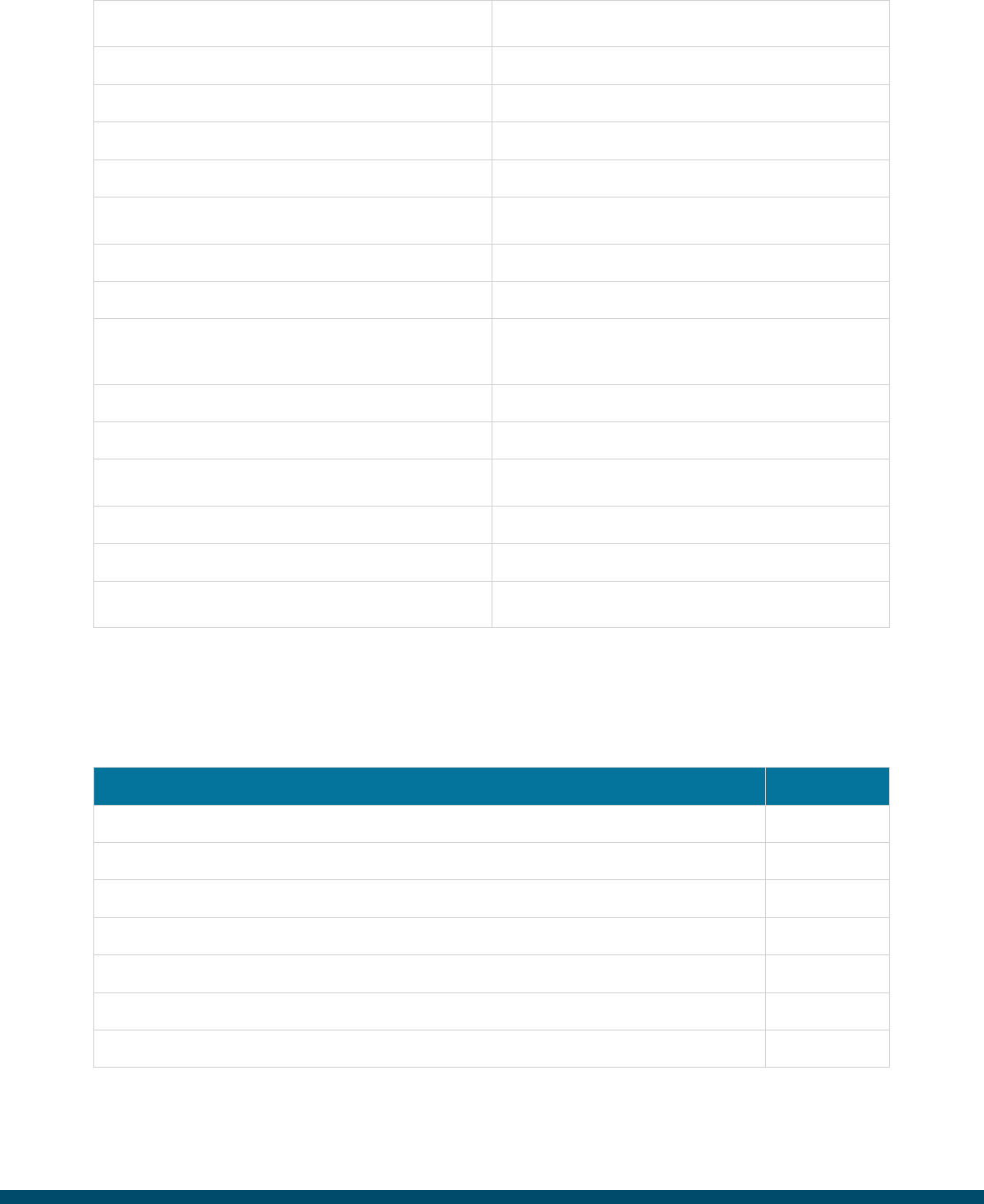

It is further acknowledged that the following organisations were involved in the production of EAPPRI Edition 2.0 which

forms the basis for this EAPPRIv3.0. .

NATIONAL AIR TRAFFIC SERVICES NATS UK • Karen Bolton

• Matt Ross

STOBART ATC SOUTHEND AIRPORT • Damon Knight (previously NATS)

GATWICK ATC AIR NAVIGATION SOLUTIONS • Graham Wadeson

ANA AEROPORTOS DE PORTUGAL • Pedro Reis

AVINOR AERODROMES • Mette Krokstrand

BRUSSELS AIRPORT COMPANY • Dirk Geukens

• Davy van Hyfte

COPENHAGEN AIRPORT • Robert Strauss

GENEVA AIRPORT • Patricia Fellay

GROUPE ADP CDG • Noemie Vellou

• Arnaud Guihard

• Jeremy Baton

AGENCIA ESTATAL DE SEGURIDAD AÉREA AESA • Jorge Reyes Fiz

UK CAA • Andrew Badham

DIRECTION DE LA SÉCURITÉ DE L'AVIATION CIVILE DSAC • Geoffroy Chevalier

• Fabrice Alger

UK FLIGHT SAFETY COMMITTEE • Dai Whittingham (Chairperson)

WSP USA • Gael Le Bris (formerly Groupe APD)

INDEPENDENT • Mike Edwards (Homefield ATM Safety contracted

to EUROCONTROL)

ORGANISATION

EUROPEAN AVIATION SAFETY AGENCY EASA

BRITISH AIRPORTS AUTHORITY NOW HEATHROW AIRPORT HOLDINGS LIMITED BAA

EUROPEAN COMMERCIAL AVIATION SAFETY TEAM NOW SUSPENDED ECAST

INSPECTIE VERKEER EN WATERSTAAT, MINISTERIE VANINFRASTRUCTURE EN MILIEU THE NETHER

LANDS

INTERNATIONAL FEDERATION OF AIR TRAFFIC CONTROL ASSOCIATIONS IFATCA

INTERNATIONAL COUNCIL OF AIRCRAFT OWNERS AND PILOT ASSOCIATIONS IAOPA

INTERNATIONAL FEDERATION OF AIRLINE PILOTS ASSOCIATION IFALPA

7

This version of European Action Plan for the Prevention of

Runway Incursions (EAPPRI) recognises the emergence of

EU provisions intended to improve runway safety in Europe.

However, like its predecessors, this third version of EAPPRI

continues to recognise the International Civil Aviation

Organisation (ICAO) Standards and Recommended

Practices (SARPS); it is therefore suitable for universal

application. The ICAO runway incursion definition (also

adopted by the EU) is “any occurrence at an aerodrome

involving the incorrect presence of an aircraft, vehicle or

person on the protected area of a surface designated for

the landing and take-off of aircraft.”

Since the first release of the EAPPRI, aerodrome local

Runway Safety Teams have been established at hundreds

of airports across Europe. The implementation of the

recommendations contained in the first and second

versions of the Action Plan has been extensive, thanks

to these teams and the organisations that support them.

In 2008, the European Aviation Safety Agency (EASA)

embedded this concept as an essential requirement

to the European Union “EASA Basic Regulation”, a

key element in helping to raise the safety of runway

operations at European airports. More recently, the

Commission Regulation No 139/2014 (or “Aerodrome

Regulation” as it is sometimes known), and its associated

Acceptable Means of Compliance (AMC) and Guidance

Material (GM), further elaborate the importance of these

runway safety arrangements. Other EU legal instruments

covering standardised European rules of the air (SERA);

air operations; the reporting, analysis and follow-up of

occurrences in civil aviation; common requirements for

the provision of air navigation services; and technical

requirements and administrative procedures relating to

air traffic controllers' licences and certificates also impact

runway safety to one degree or another.

Many operational staff have experienced a runway

incursion and have contributed to the future prevention

of runway incursions through incident reports. These

reports have taught us that the majority of contributory

and causal factors are concerned with communication

breakdown, ground navigation errors and inadequate

information in the cockpit.

The runway incursion problem remains a significant safety

issue. One of the important challenges is that pilots and

drivers on a runway without a valid ATC clearance believe

they have permission to be there

INTRODUCTION AND BACKGROUND

8

The aspiration to present aerodrome NOTAM information

in a digitised, interoperable exchange format (i.e. graphical

display) should be continued.

Emerging technologies such as those associated with

Remote Tower Operations (RTO) present opportunities

and threats as far as maintaining the safety on and

around runways is concerned. Similarly, authorised

remotely piloted aircraft systems (RPAS) or ‘drones’ need

to be accommodated on and around aerodromes whilst

ensuring the continuation of safe operations.

Other technologies on the ground (in ATC and/or on

the aerodrome) as well as those on board aircraft are

becoming increasingly available. Given that EAPPRI’s

status is wholly advisory, it is not appropriate to make

direct recommendations to implement these various

technologies. However it is right to acknowledge their

presence and provide brief information and guidance so

that operational practitioners can make further enquiries

to decide for themselves the merits, or otherwise, of

certain technological advances as applicable in their local

operation.

Examples of aerodrome local Runway Safety Team

achievements are contained in the guidance materials

shown in the appendices to this document and some are

also highlighted below.

ICAO

ICAO has introduced Annex 19, Safety Management

to bolster the industry wide implementation of Safety

Management Systems (SMS). In addition, it has published

Doc. 9981, PANS Aerodromes (PANS ADR) to provide more

information about aerodrome operations including the

prevention of runway incursions; a new edition is planned

to be published in 2019 and to become applicable in

2020. The ICAO Aerodrome Design and Operations Panel

also continues to develop SARPs for runway safety in

Annex 14 – Aerodromes, Volume 1 - Aerodrome Design

and Operations, as well as PANS Aerodromes. ICAO is

also developing a new high-level runway safety strategy

document to support the future ICAO Global Aviation

Safety Plan (GASP).

At a more grassroots level, ICAO published the second

edition of the Runway Safety Team (RST) Handbook

in 2015; this document provides practical guidance

about how to set up and manage aerodrome local

RSTs. ICAO also established the concept of RST

Go-Teams to assist States and airports in establishing RSTs.

The implementation of Safety Management Systems

(SMS) and the establishment of aerodrome local Runway

Safety Teams (RST) have undoubtedly enabled aircraft

operators, air navigation service providers and aerodrome

operators to improve operational runway safety. In

the spirit of continuous improvement, however, new

recommendations in this document challenge industry

partners and regulators to re-assess the effectiveness

of these working arrangements and practices to ensure

that they continue to be optimised to deliver safe runway

operations, including the prevention of runway incursions.

Practical use of the ICAO runway incursion definition is

intended to allow runway incursion data to be compared,

common causes and contributory factors to be identified

and lessons to be shared. However, experience has shown

that these ideals are threatened because the interpretation

of the definition still varies across the industry. Further

work may be necessary, but as an intermediate step a

new appendix provides additional guidance aimed at

improving the overall consistency of runway incursion

data and a better understanding of runway collision risk.

Aerodrome vehicle driving operations are an ongoing

hazard for safe runway operations. A number of new

recommendations and associated guidance would

further strengthen the existing comprehensive barriers, if

implemented. The use of synthetic trainers (simulators) to

train airside drivers is bringing economic and operational

benefits to some airports. Control and management of

aerodrome works in progress/contractors are given more

prominence in this document; additional aerodrome

design considerations are also promoted.

Operational safety studies continue to show that the

H24 use of stop bars can be a powerful runway incursion

prevention barrier. Previous editions of EAPPRI included

H24 stop bar use in Guidance Material but in this version

the practice is elevated to Recommendation status for

aerodrome operators and air navigation service providers

to consider.

Regulators and national aviation authorities have an

important role to play in setting the national tone as far as

runway safety and runway safety promotion is concerned.

New Recommendations ask national authorities to

strengthen this activity and their oversight of operators’

SMS.

This document recognises the proliferation of aeronautical

information (e.g. NOTAMs) that pilots, in particular, are

expected to assimilate. New Recommendations call for

improvements of Aeronautical Information Management

(AIM) and the simplification of the way it is presented.

WHAT’S CHANGED

9

EU and EASA

New EU Regulations have been introduced in recent

years. These regulations, covering aerodrome operations,

occurrence reporting and design, are aimed at establishing

safe operations of aerodromes and ensuring that every

effort is made to reduce the number of accidents and

incidents (including those affecting runway operations).

Moreover, EASA is placing more focus on Safety Promotion

activities and incorporates runway safety actions in the

European Plan for Aviation Safety (EPAS).

SESAR

The Single European Sky ATM Research (SESAR) project has

developed, and is developing, a number of technological

solutions to improve airport operations; many of these

have direct or indirect safety benefits. A SESAR deployment

plan is in place to manage the implementation of these

new and emerging technologies; some of those that can

potentially help prevent runway incursions are described,

in brief, in Appendix M.

EUROCONTROL – Network Manager

Since 2011, the EUROCONTROL Network Manager has

introduced the concept of ‘Top 5’ Safety priorities. Some of

these priorities are related to runway incursion prevention.

Associated ‘Top 5’ Operational Safety Studies covering

‘landing without ATC clearance’, ‘detection of occupied

runway’ and ‘sudden high energy runway conflicts’ have

been commissioned. The resulting reports serve as a cross

domain reference and source of information and advice

in case stakeholders undertake operational safety and

improvement to address each priority area.

Airport Council International (ACI)

ACI has introduced its Airport Excellence (APEX) in Safety

Programme which is designed to help airports identify

and mitigate aviation safety vulnerabilities through peer

review missions, education, mentoring and best practice

guidance. This activity is complementary to the ICAO RST

Go-Teams concept/model (and vice versa).

IFALPA/ECA/ACI

IFALPA, in conjunction with ACI, is developing a method

for naming taxiways, runways and their intersections and

holding positions, to remove ambiguity. This method is

being considered by ICAO and new guidance to industry

is expected to be published in the future.

Civil Air Navigation Services Organisation (CANSO)

To support the management of runway safety risk, CANSO

has introduced a Runway Safety Maturity Checklist which

is designed to help organisations identify and prioritise

areas for runway safety improvement from different

perspectives.

10

• Implement the change.

• Monitor the effectiveness of the change.

Changes to aerodrome operations may involve the

introduction of new aerodrome infrastructure including

visual aids, additional technologies or new ways to use the

existing platform. Prior to making local changes that differ

from EU/ICAO provisions, consideration should be given

to the potential global effect on air traffic management. A

considered approach to local change would be to create

an operational evaluation period prior to permanent

introduction of the desired operation. If you are satisfied

with the outcome of the operational evaluation, consult

your regulator to determine the overall effect on the

air traffic management system prior to permanent

introduction to operations.

For further information on the content of

this Action Plan, please contact:

Runway Safety Office, Safety Unit,

Network Management,

EUROCONTROL, Rue de la fusée 96,

B-1130 Brussels, Belgium

Phone: + 32 (0)2 729 3965

runway.safety@eurocontrol.int

http://www.eurocontrol.int/articles/runway-safety

Runway incursions are still considered one of the most

serious safety threats amongst operational personnel.

The publication of this 3

rd

edition of the European Action

Plan for the Prevention of Runway Incursions (EAPPRI)

provides an opportunity for aviation industry stakeholders

and organisations to re-focus and re-energise their runway

incursion prevention activities.

As a starting point, it is suggested that organisations

review and re-assess their implementation of the

recommendations from the previous version before

embarking on the implementation of the new

recommendations in this document. Special attention

should be given to ensuring that SMSs provide the

necessary support (processes, procedures, practices) to

facilitate effective runway incursion prevention activities.

In addition, aerodrome local Runway Safety Teams should

re-assess all aspects of their work to ensure that they are

delivering effective runway safety outcomes.

Aerodromes which have not yet established a local Runway

Safety Team are encouraged to do so - proportionate to

their size and complexity - as soon as possible.

As in the previous edition, this version of EAPPRI

continues to emphasise the need for a mutual exchange

of information and data between organisations in order to

facilitate lesson learning and assisting in the enhancement

of runway safety.

To assist your organisation to plan this activity, the

following generic approach is suggested:

• Confirm your organisation’s usage of the relevant

EU regulations and ICAO provisions - note any

discrepancies.

• Identify any changes required in your operations.

• Identify any changes required from your operating

partners.

• Document the change requirements.

• Invite your internal and where appropriate external

partners to a joint meeting, using the aerodrome

local Runway Safety Team to discuss the change

requirement and possibly identify solutions.

• Conduct an appropriate safety assessment of the

proposed change.

IMPORTANT AND URGENT ACTIONS

11

“Shall”

is used in this document to signify that, while a

recommendation does not have the force of a mandatory

provision, its content has to be appropriately transposed

at local level to ensure its application. (This is the case

of an ANSP transposing into its Operations Manual the

content of applicable recommendations in order to have

controllers complying with them.)

“Should”

is used in this document to signify that the application of

the recommendations would be beneficial to safety either

as a ‘best practice’ or as a potential mandatory provision,

after a local assessment.

“Assess”

is used in this document to indicate that you assess the

current position/situation and decide if and how changes

should be made to increase their effectiveness.

“Do Not”

as used in some Recommendations this document, is an

imperative statement to signify that any recommendation

and associated action must not be contradicted unless a

local feasibility/safety assessment has been undertaken.

“Regulator”

is used in this document to refer not only to the

organisation responsible for designing and making

the regulatory framework progress, but also to the

organisation that ensures that this regulatory framework

is applied among the aviation undertakings it oversees.

In some recommendations of this document, the term

“regulator” refers also to the entity in charge of promoting

safety among the aviation undertakings under its

responsibility.

Aerodrome Flight Information Service

Officers (AFISOs)

The Recommendations and Guidance Materials in this

document that are applicable to air navigation service

providers/air traffic controllers may also be relevant to

AFISOs according to the local aerodrome context and

the rules, regulations and practices and procedures that

govern the provision of AFIS.

“H24”

means either full H24 operations (where aerodromes

are open all day/night, or during published aerodrome

operating hours when ATC is being provided (and not just

in reduced visibility conditions and/or at night).

‘Active’ Runway

EASA GM1 ADR – DSN.M.745 states that “Active runway is

to consider any runway or runways currently being used

for take-off or landing. When multiple runways are used,

they are all considered active runways.”

Note:

Many of the EU Regulations listed in this document

are supported by, and as necessary, should be read in

conjunction with, EASA Certification Specifications (CS),

Acceptable Means of Compliance (AMC) and Guidance

Material (GM) which are intended to assist in the

implementation of the relevant EU regulation.

These so-called “soft laws” can be accessed via:

https://www.easa.europa.eu/document-library/agency-

rules-overview.

MEANING OF TERMS AND ACTION VERBS IN

RECOMMENDATIONS AND GUIDANCE MATERIALS

12

13

RECOMMENDATIONS

1.1 General principles

1.2 Aerodrome operator issues

1.3 Communications

1.4 Aircraft operator issues

1.5 Air navigation service provider issues

1.6 Data collection and lesson sharing

1.7 Regulators issues

1.8 Aeronautical information management

1.9 Technology

1.10 Civil military

2.0 Future work

EUROPEAN ACTION PLAN FOR THE PREVENTION

OF RUNWAY INCURSIONS

14

1.1 GENERAL PRINCIPLES

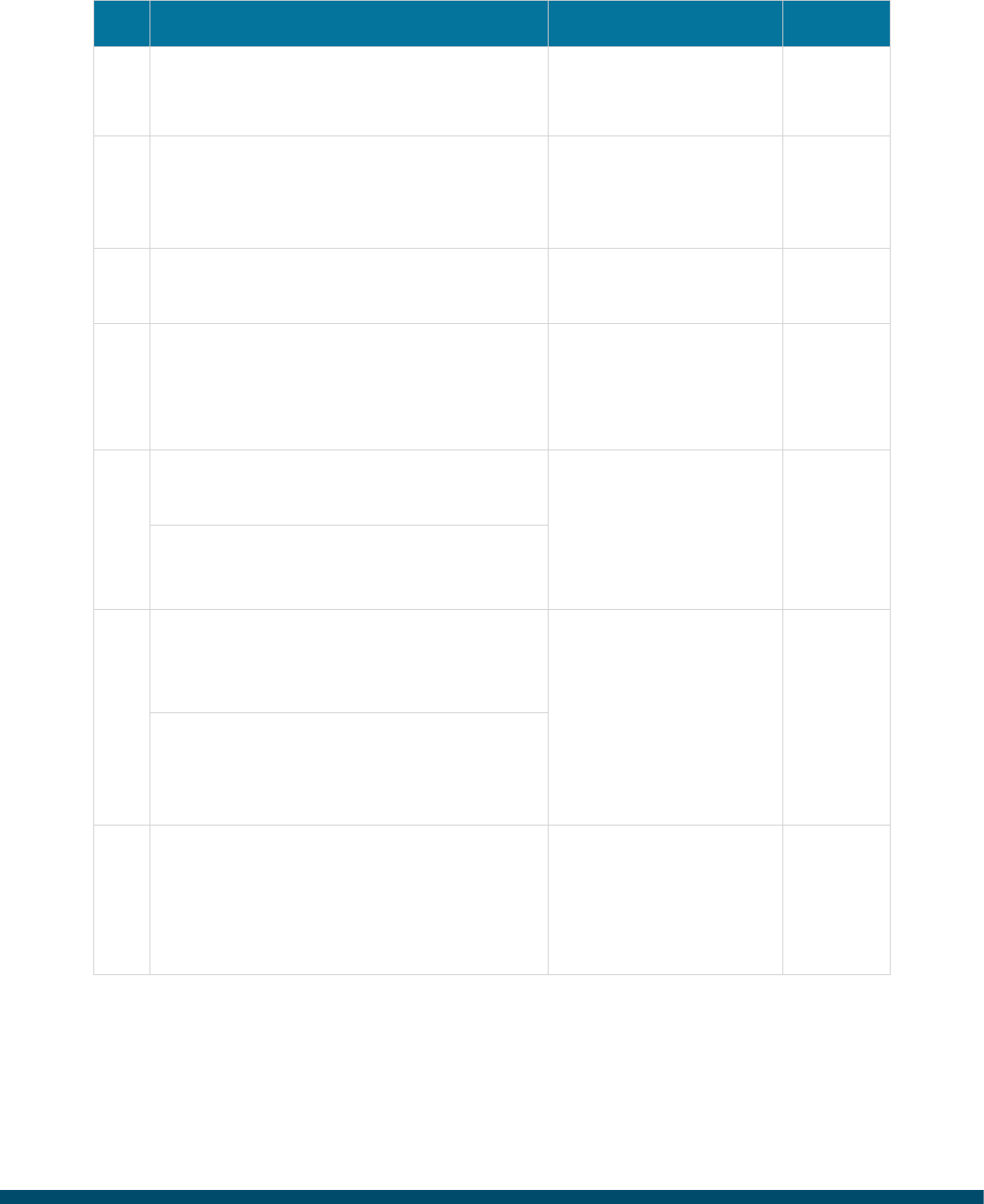

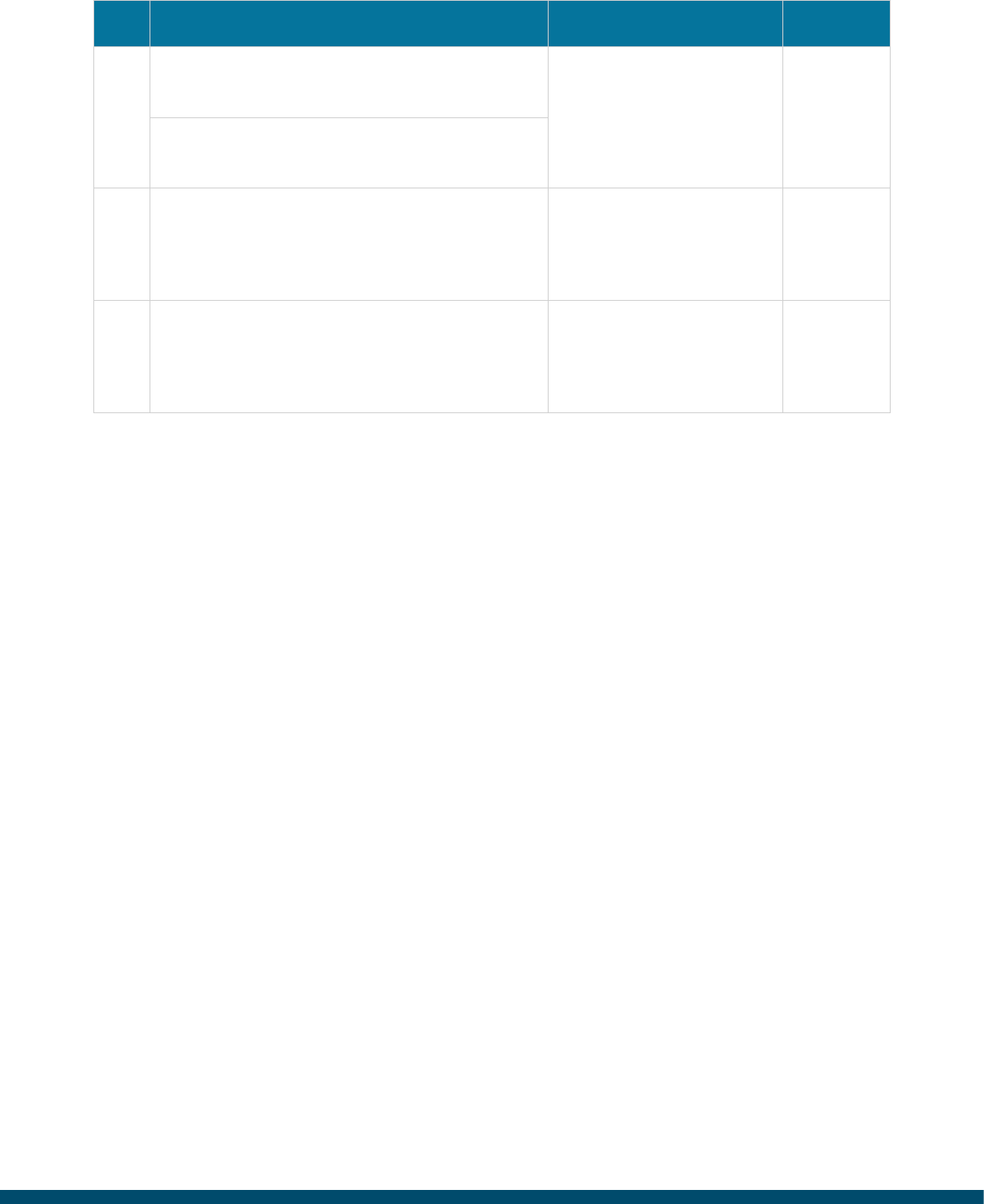

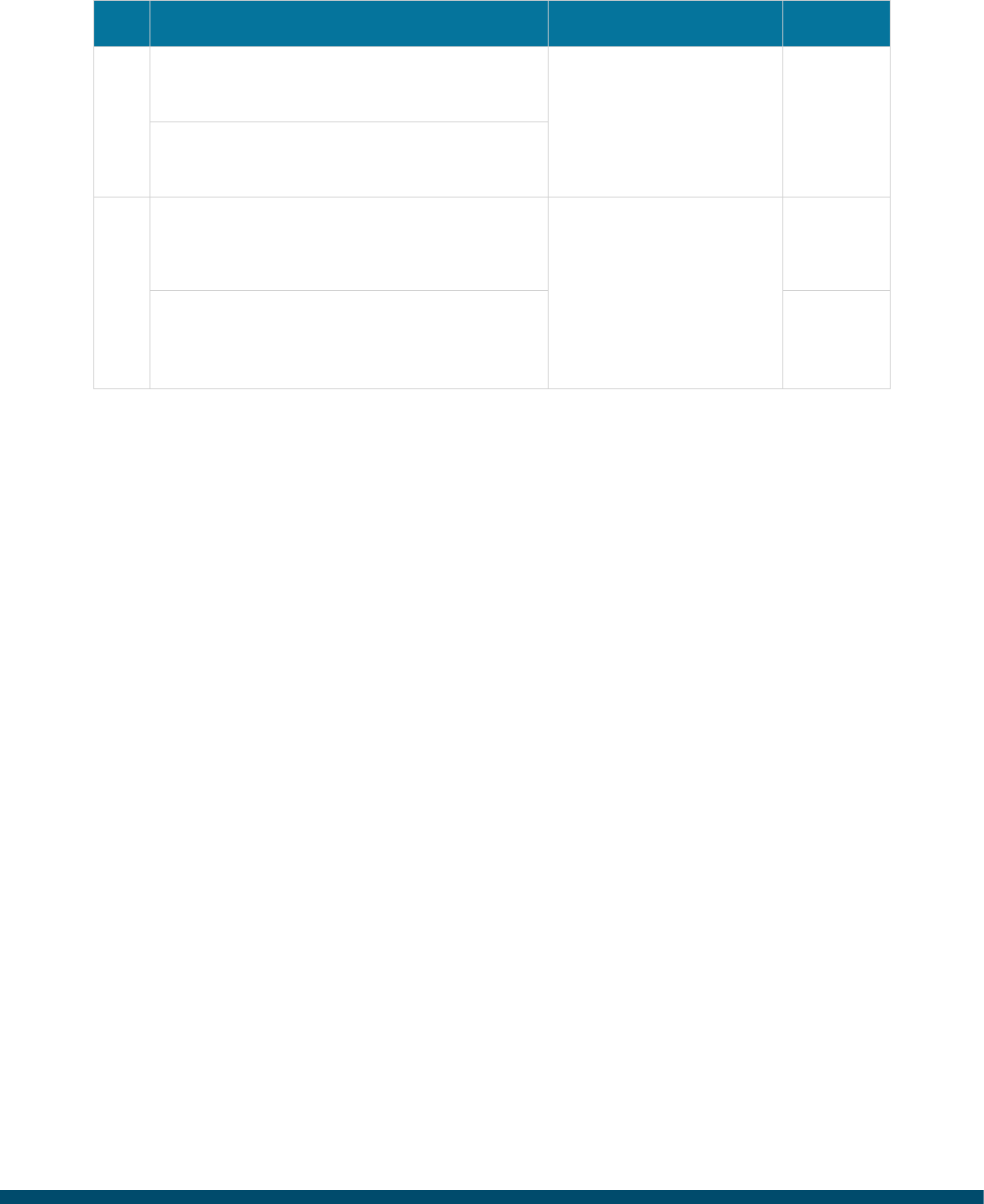

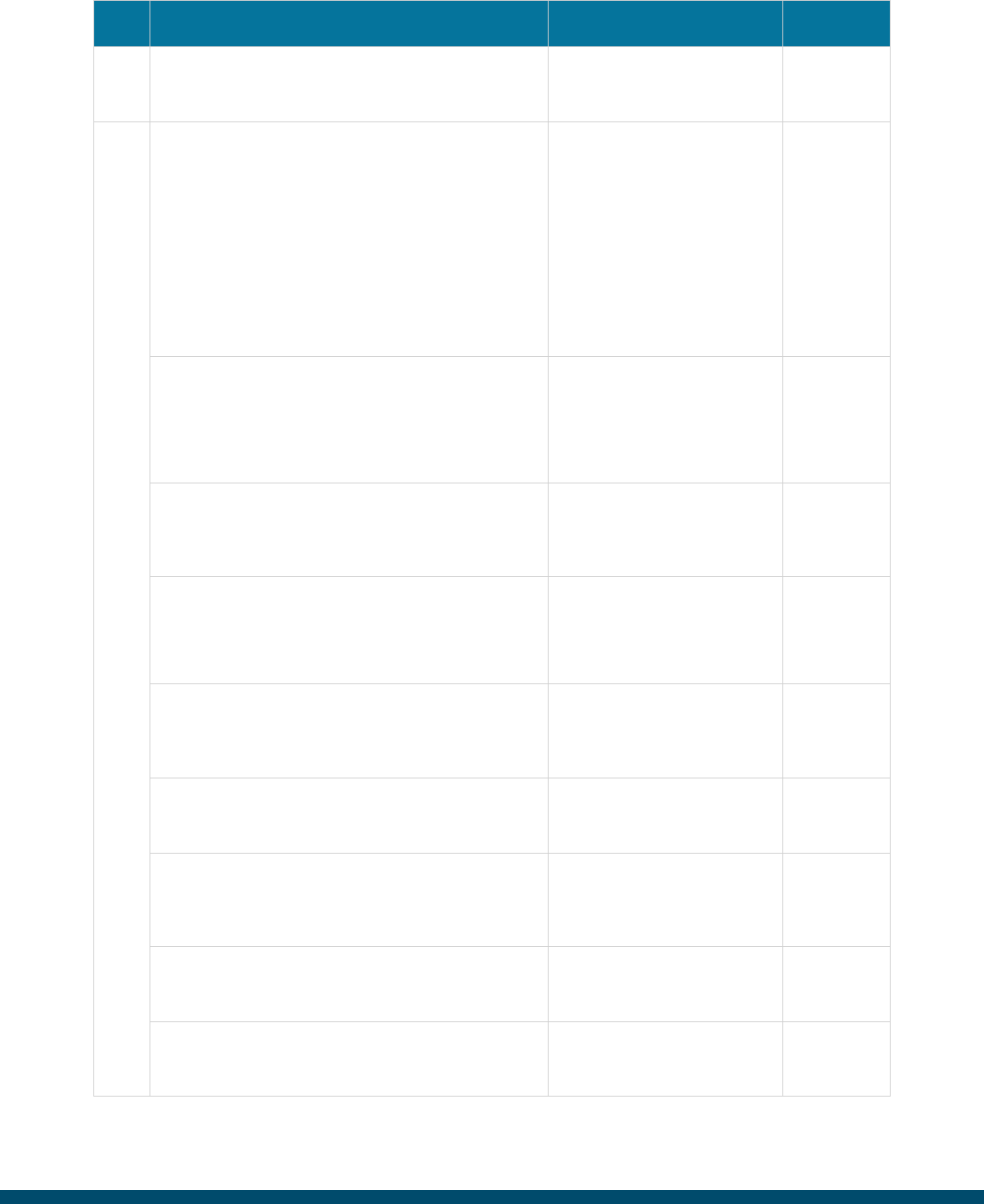

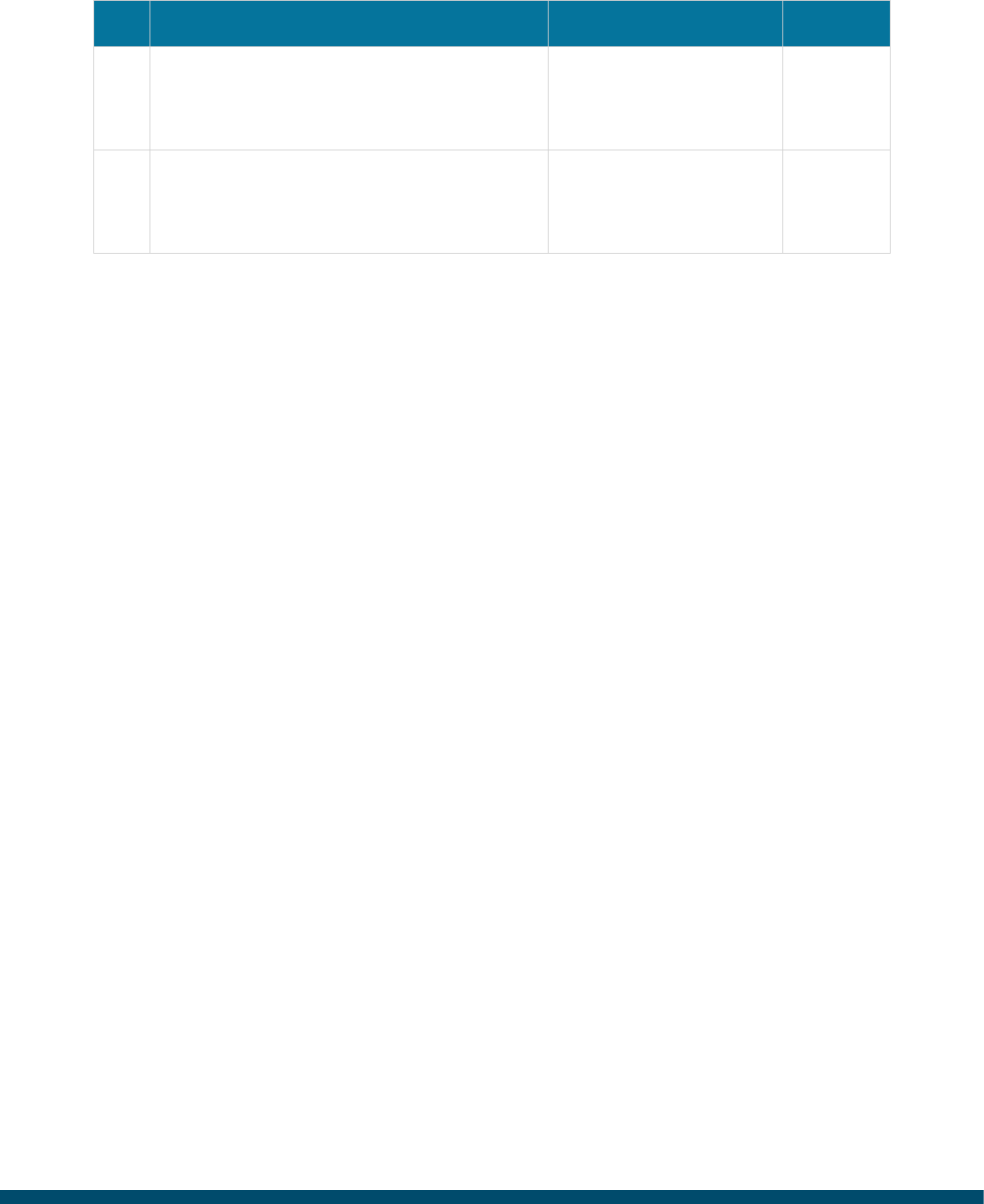

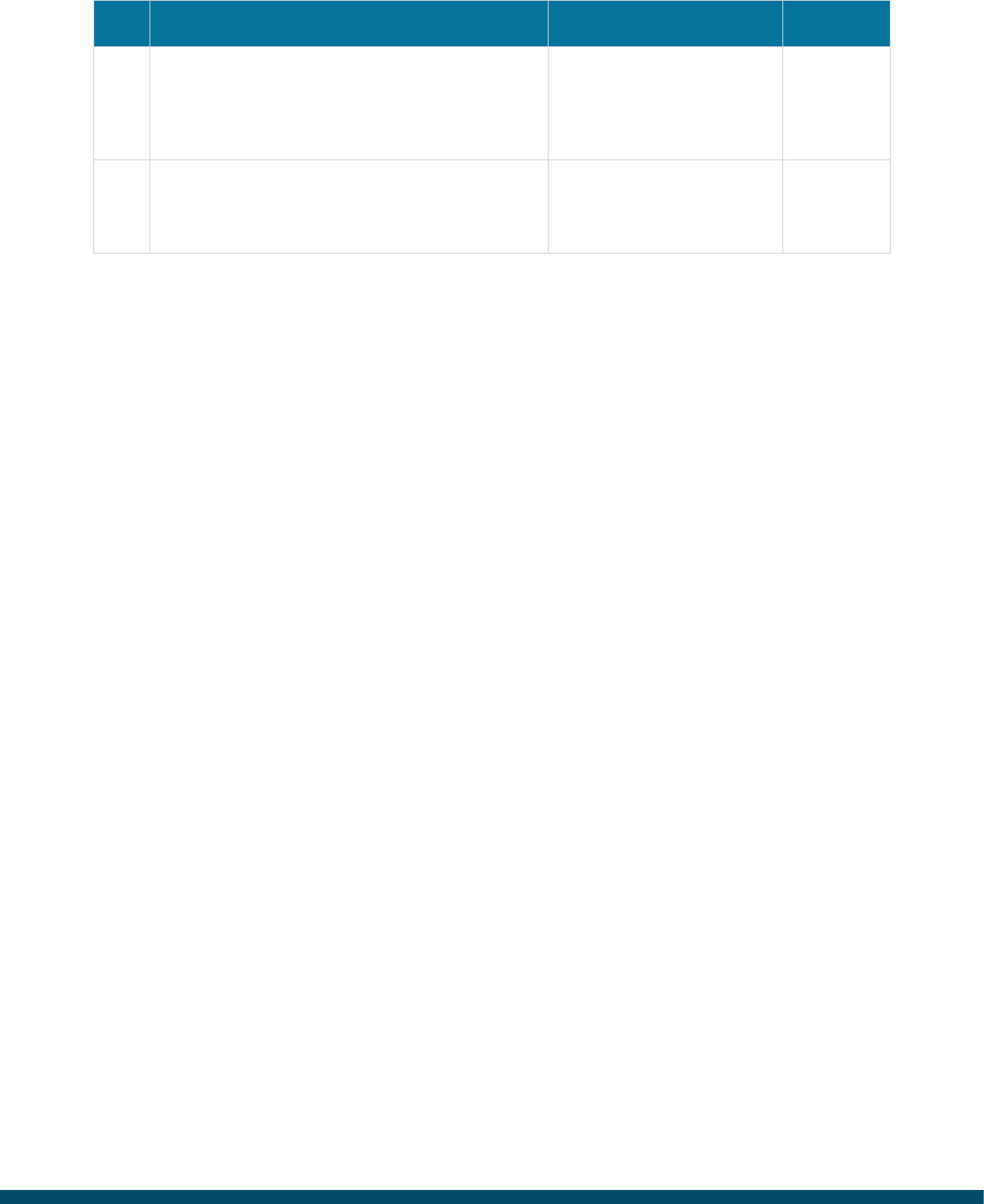

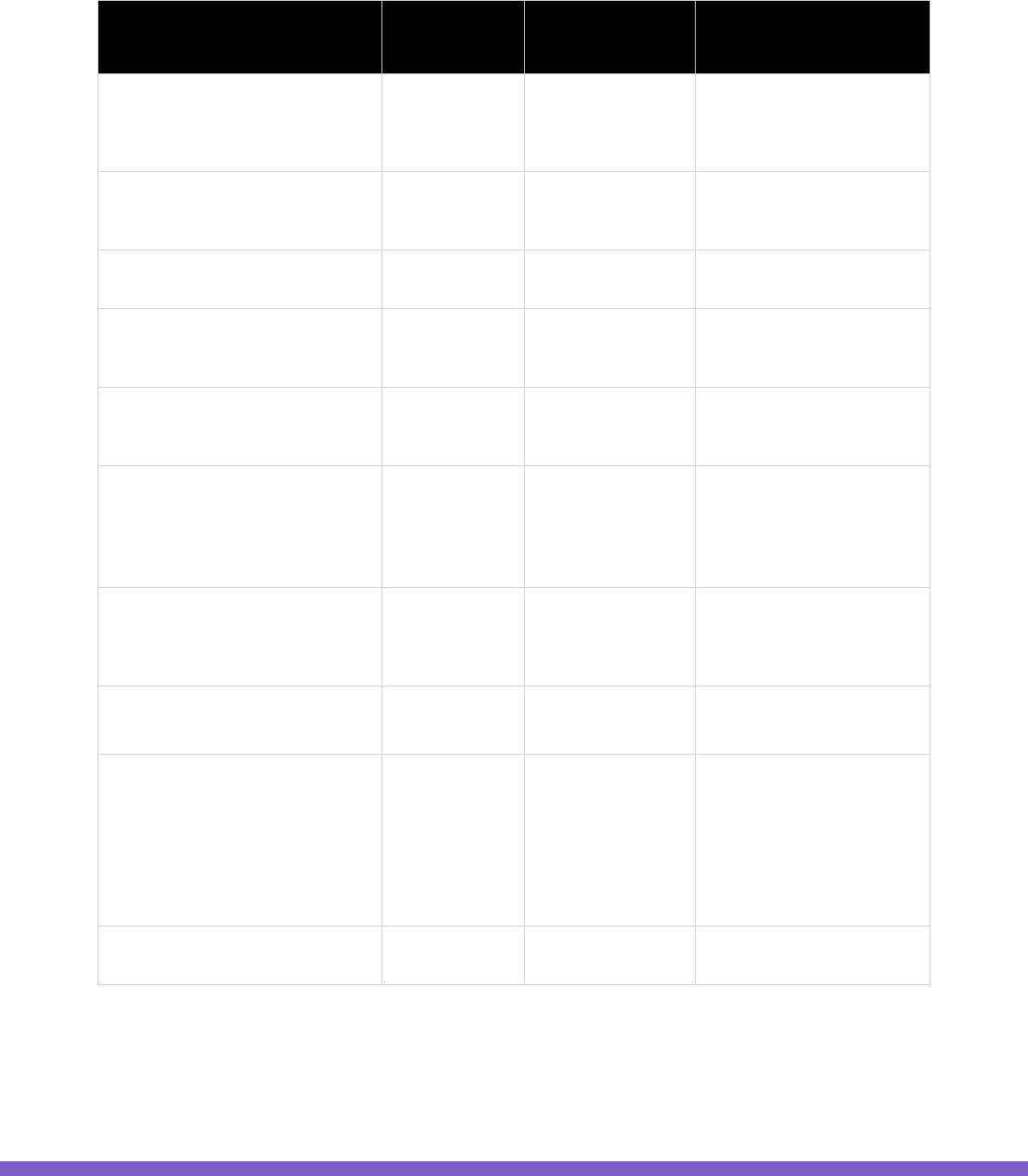

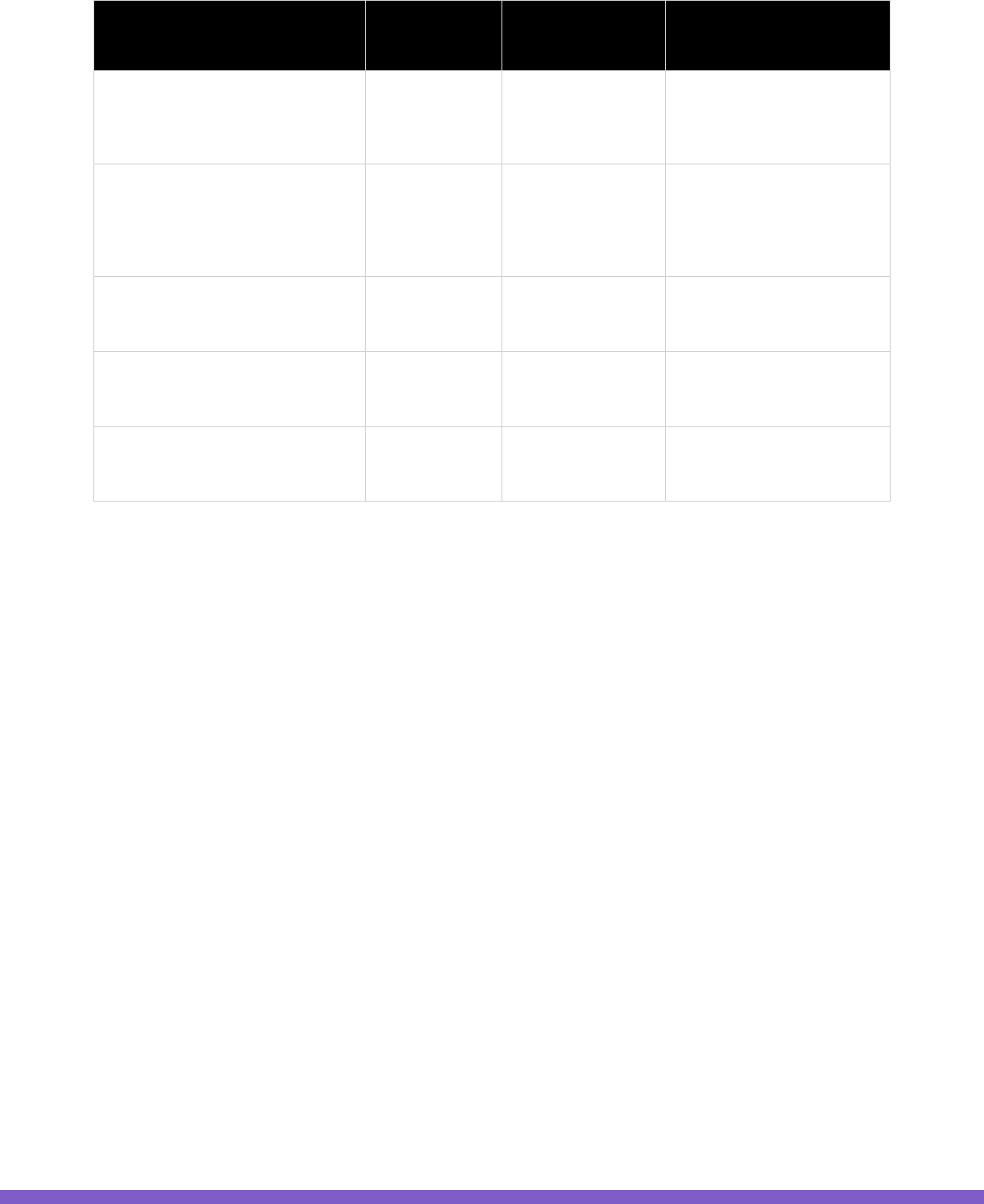

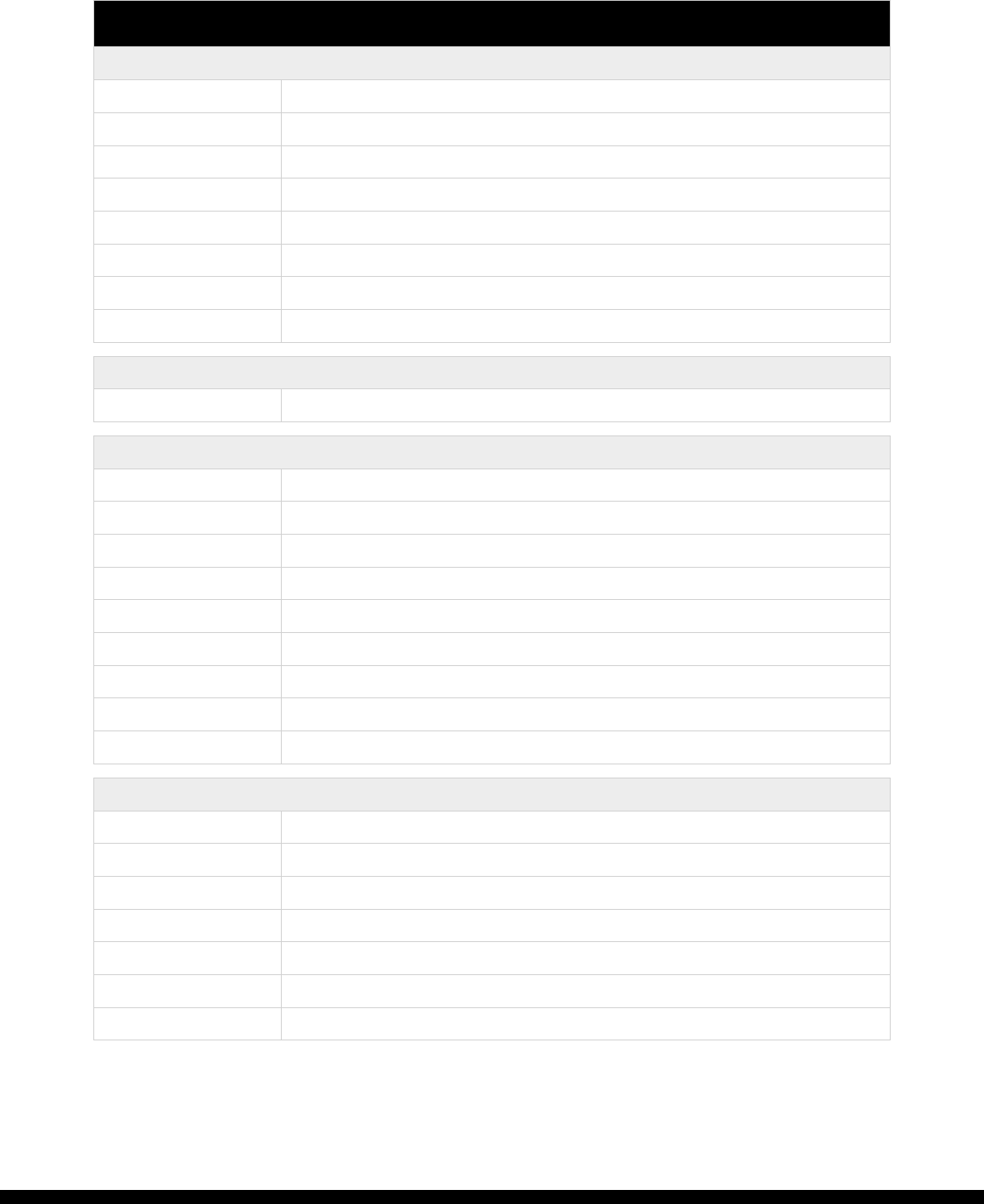

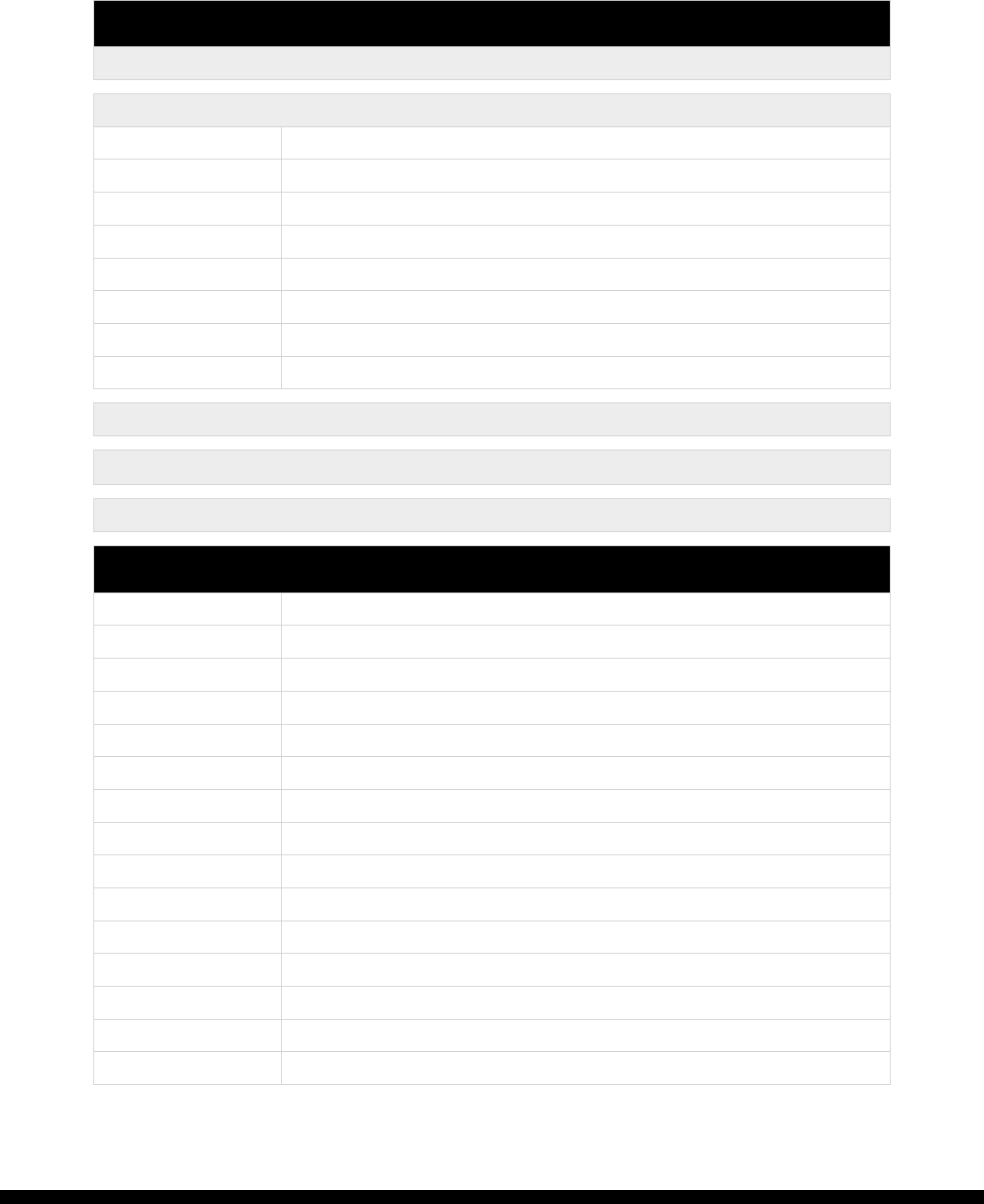

# Recommendation Action Guidance

1.1.1 Assess the implementation and operation of aerodrome local

Runway Safety Teams (RST) and consider if and how changes

could be made to increase their effectiveness in developing

runway safety actions.

Aerodrome Operators,

Air Navigation Service Provider,

Aircraft Operators, Regulator.

Appendix B

1.1.2 Implement local runway safety awareness campaign plans

and assess their effectiveness at each aerodrome for Air Traf-

fic Controllers, Pilots and Vehicle Drivers and other personnel

who operate on or near the runway. Consider format, method

of delivery, frequency and feedback.

Aerodrome local Runway

Safety Team.

Appendix B

1.1.3 Ensure that all infrastructure, practices and procedures relat-

ing to runway operations are in compliance with ICAO and,

where applicable, EU provisions.

Aerodrome Operator (lead),

Air Navigation Service Provider.

Appendix J

Appendix K

Appendix L

1.1.4 Promote and make available specific joint training and famil-

iarisation in the prevention of runway incursions to Pilots, Air

Traffic Controllers and Manoeuvring Area Vehicle Drivers.

Aerodrome local Runway Safety

Team,

Air Navigation Service Provider,

Aircraft Operator,

Regulator,

Aerodrome Operator.

Appendix B

1.1.5 a.

Assess how the subject of Runway Safety is included within

initial and refresher/recurrent training for operational staff:

Aircraft Operator,

Air Navigation Service Provider,

Aerodrome Operator,

Regulator,

Training establishments.

b.

Consider what more can be done to include the viewpoint

and procedures of other stakeholders operating on the

aerodrome.

1.1.6 a.

Ensure that adequate information is collected on all runway

incursion incidents so that causal and contributory factors

can be identified, lessons can be learned and actions taken.

Aircraft Operator,

Air Navigation Service Provider,

Aerodrome Operator,

Aerodrome local Runway Safety

Team,

EUROCONTROL.

b.

In addition, the salient points from investigation reports

should be disseminated for Units, Organisations, and Na-

tional and European stakeholders as information that may

influence future safety improvement actions.

1.1.7 Assess the arrangements currently in place that coordinate

changes to manoeuvring area procedures, including works

in progress.

Guidance Note:

This assessment should include the role of the aerodrome

local Runway Safety Team in change management.

Air Navigation Service Provider,

Aerodrome Operator,

Regulator.

Appendix F

Appendix L

15

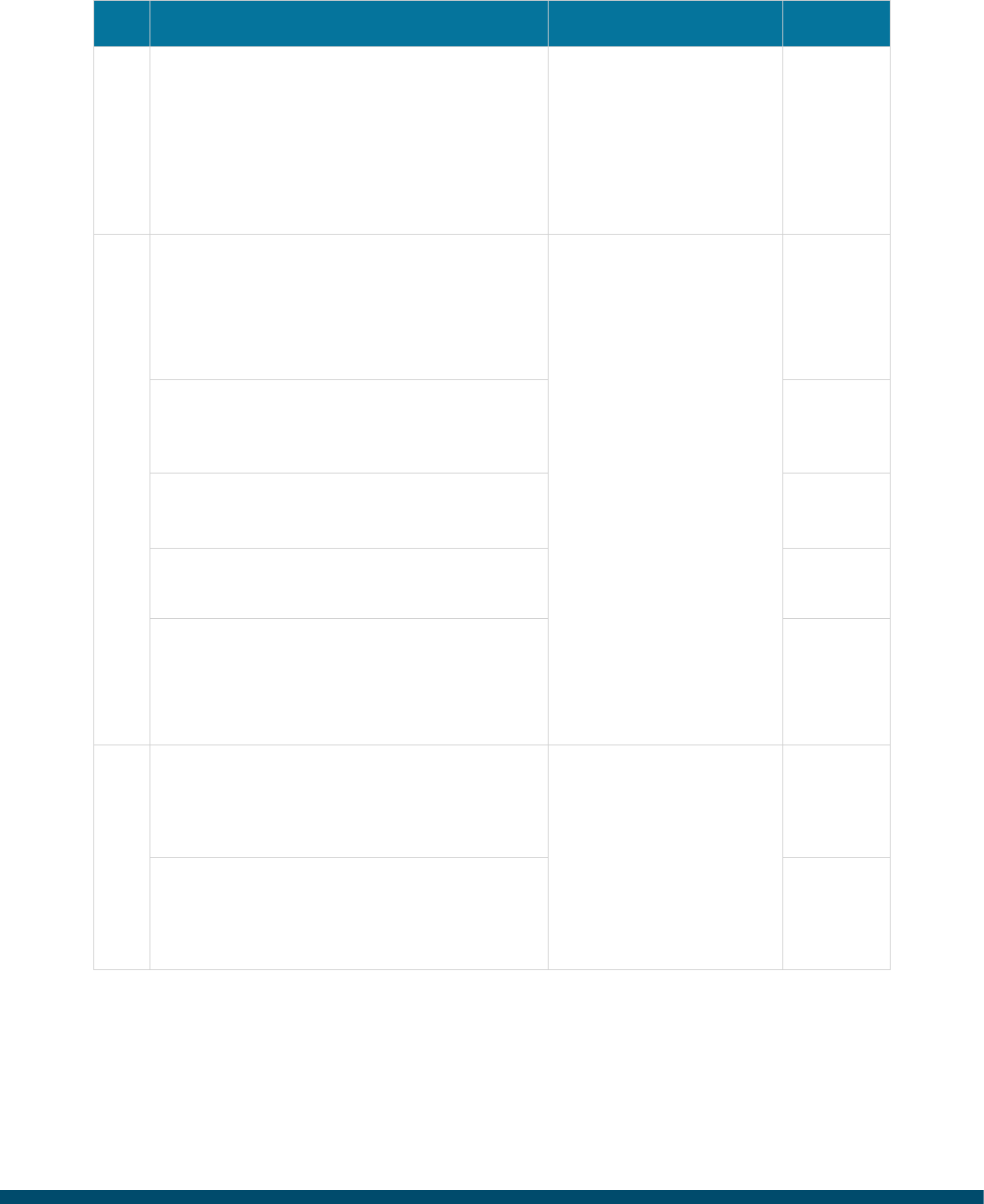

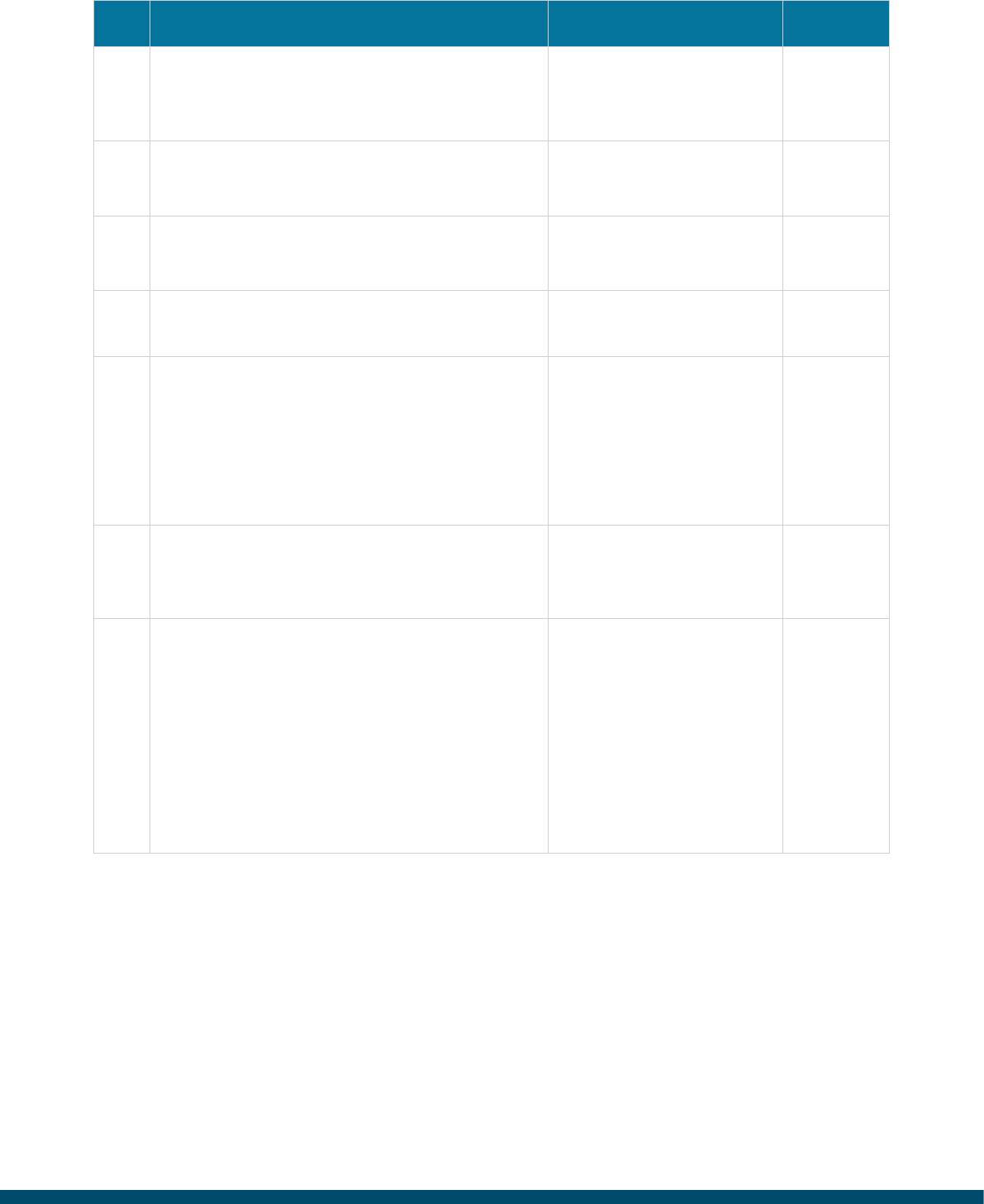

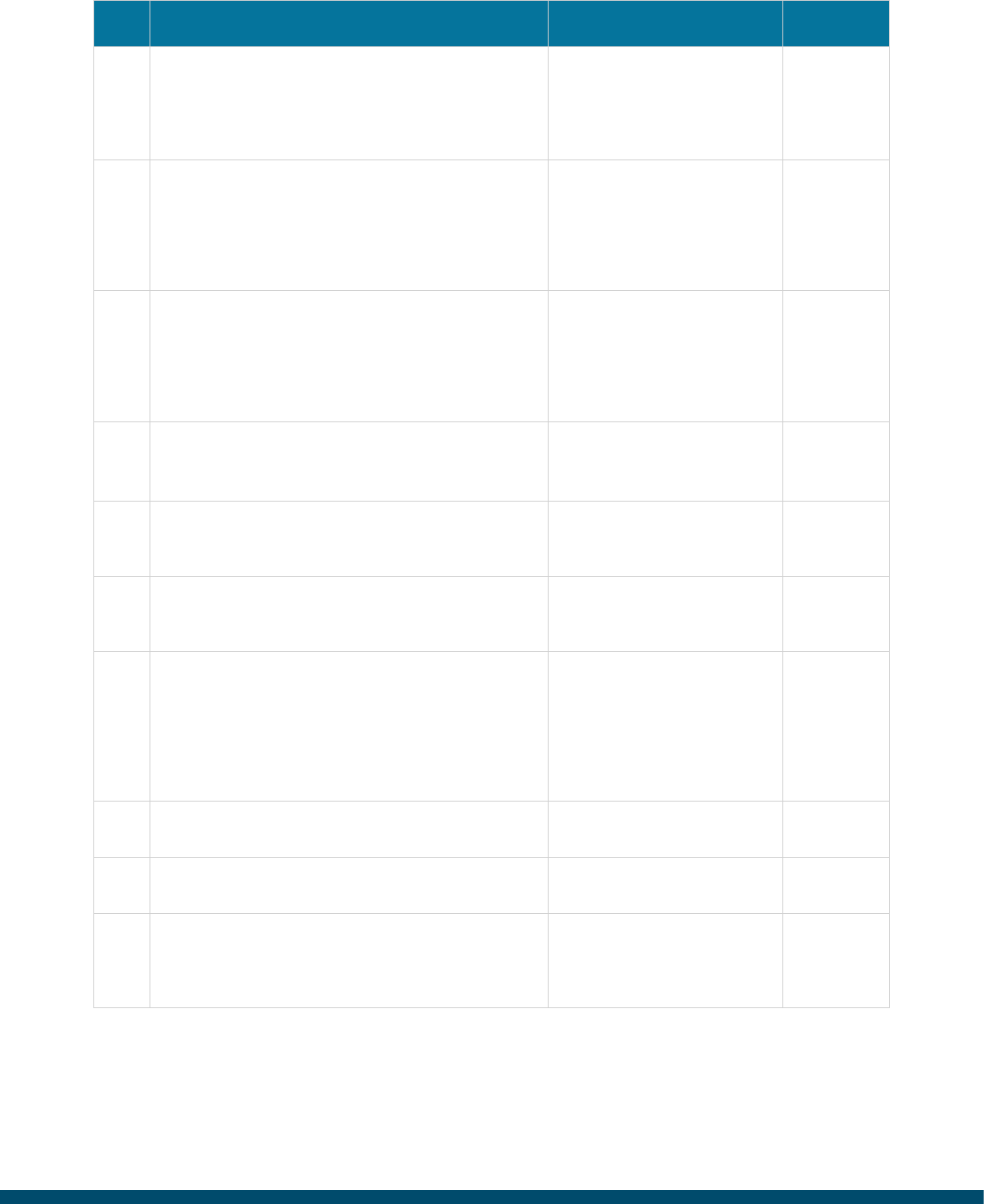

# Recommendation Action Guidance

1.1.8 a.

Assess the implementation and effectiveness of Safety

Management Systems related to runway safety activities.

Air Navigation Service Provider,

Aerodrome Operator,

Aircraft Operator,

Regulator.

Appendix G

b.

Ensure a continued focus on runway safety in internal audit

activities.

1.1.9 Continue to develop components of SMS as detailed by

ICAO, EU or EUROCONTROL (ESARR3) provisions that move

towards a data driven, performance-based safety system

approach with an emphasis on safety assurance and

identifying and sharing best practice and signs of excellence.

Air Navigation Service Provider,

Aerodrome Operator,

Aircraft Operator,

Regulator.

Appendix G

1.1.10 European stakeholders should work together to study the

interpretation of the ICAO runway incursion definition with

the aim of improving the consistency and credibility of

runway incursion reporting via appropriate regulatory

channels.

EUROCONTROL. Appendix N

16

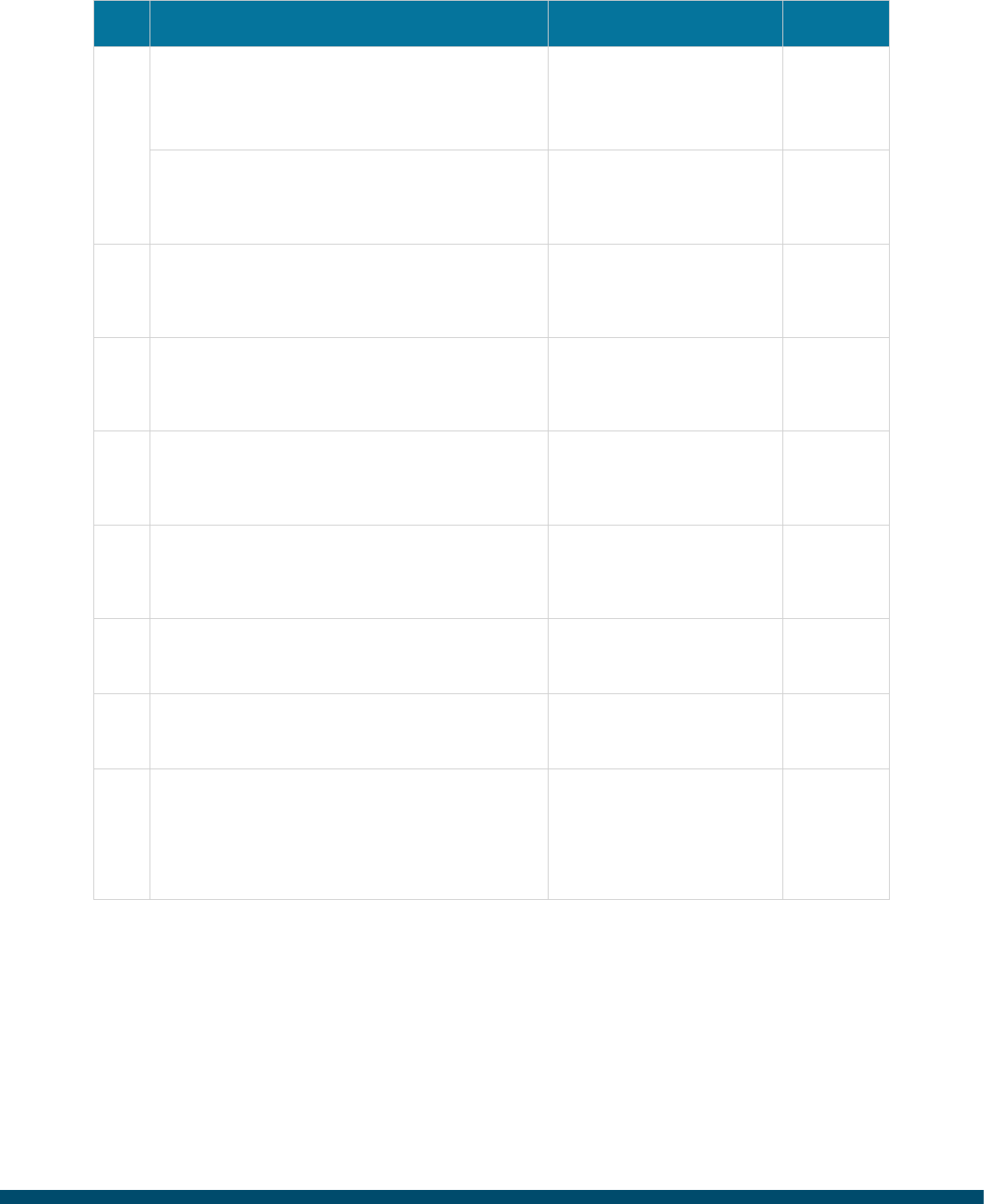

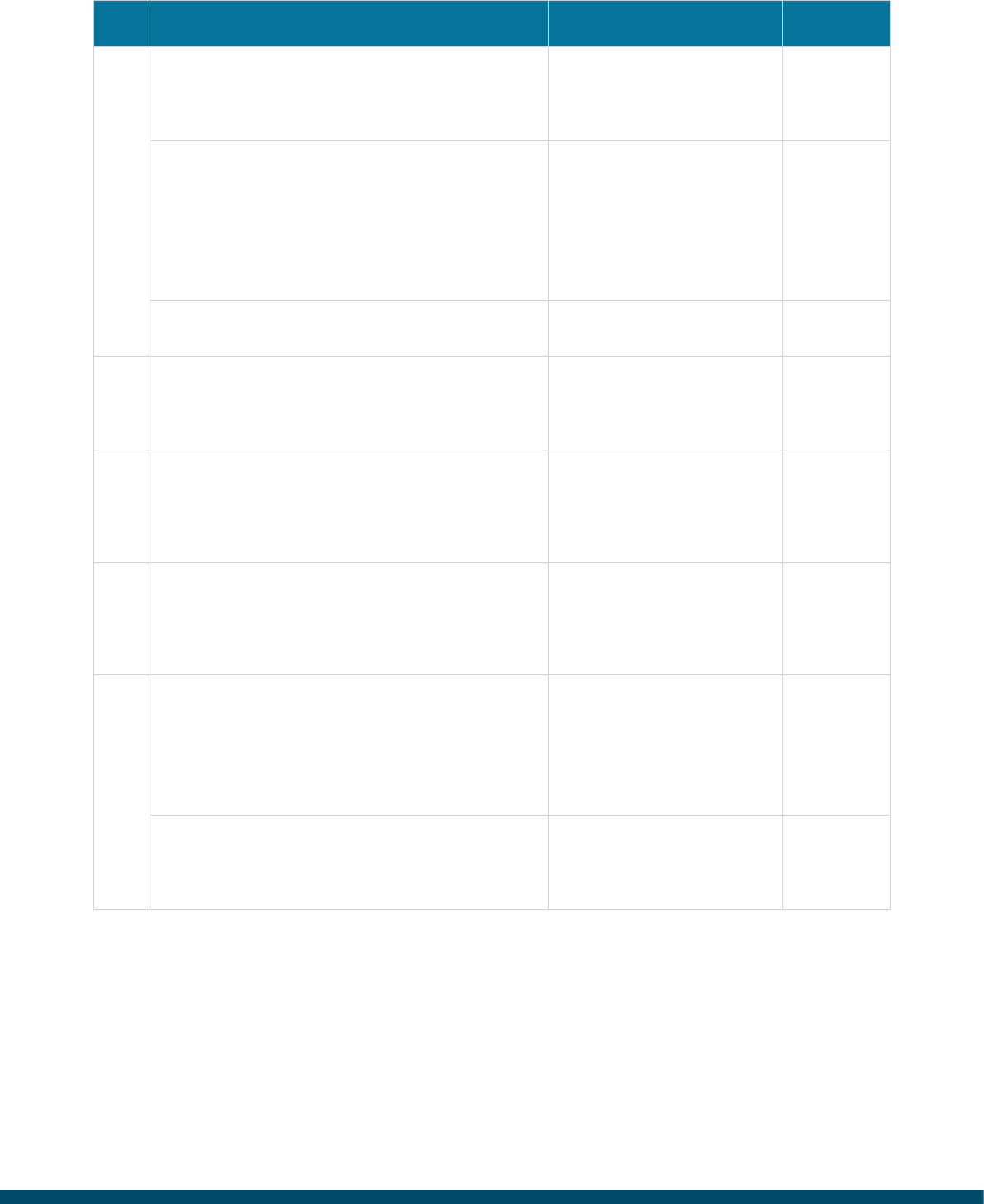

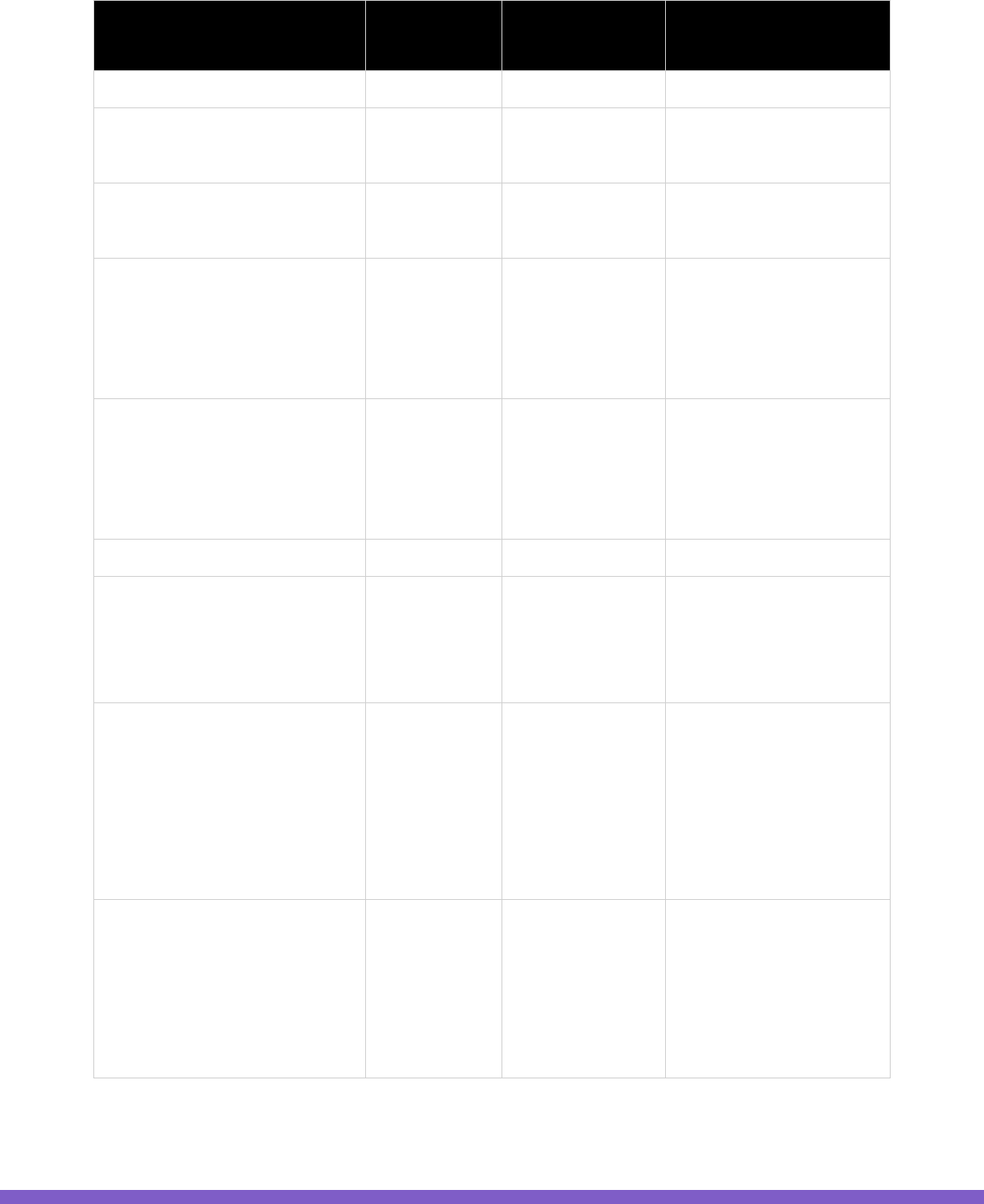

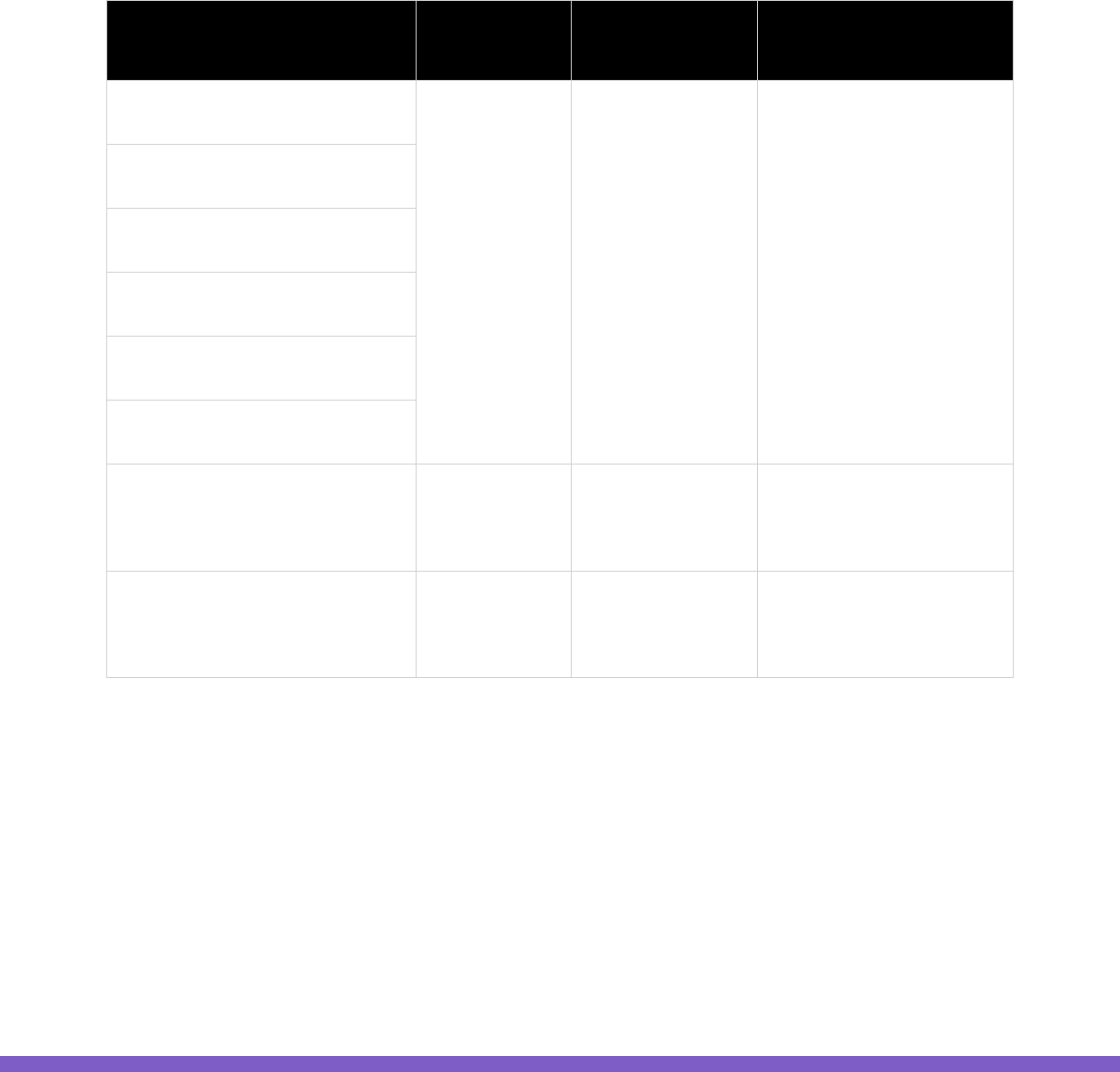

1.2 AERODROME OPERATOR

# Recommendation Action Guidance

1.2.1 Assess the implementation of maintenance programmes

relating to runway operations e.g. markings, lighting, signage

in accordance with Commission Regulation (EU) No 139/2014

and ICAO Annex 14, Aerodromes, Volume 1 - Aerodrome

Design and Operations when applicable.

a.

Ensure that signs, markings and lights are clearly visible,

adequate and unambiguous in all appropriate conditions.

Aerodrome Operator.

Appendix B

Appendix J

1.2.2 Assess all arrangements associated with aerodrome construc-

tion works/works in progress (WiP):

a.

Ensure that up to date information about temporary work

areas and consequential operational impact is adequately

presented and disseminated.

Aerodrome Operator,

Air Navigation Service Provider,

AIM Provider,

Aircraft Operators.

Appendix H

Appendix L

b.

Ensure that sufficient coordination between ANSPs and

Aerodrome Operator is in place prior to notification to the

Regulator.

Appendix H

Appendix L

c.

Ensure that existing signs are covered and markings are

removed when appropriate.

Appendix L

d.

Ensure that temporary signs and markings are clearly visible,

adequate and unambiguous in all appropriate conditions.

Appendix L

e.

Aerodrome construction contractors and other person-

nel working airside should be appropriately briefed (about

runway safety/runway incursion prevention) prior to starting

work and be properly supervised whilst they are on the

aerodrome.

1.2.3 a.

Assess formal Driver training and refresher programmes

(including practical training and proficiency checks) against

driver training guidelines e.g. the training programme frame-

work at Appendix C.

Aerodrome Operator (lead),

Air Navigation Service Provider

(support).

Appendix C

b.

Carry out regular audits of airside driving permits (e.g. check

‘recency’ of use) in particular those allowing access to the

runways, which should be as few as possible.

Appendix C

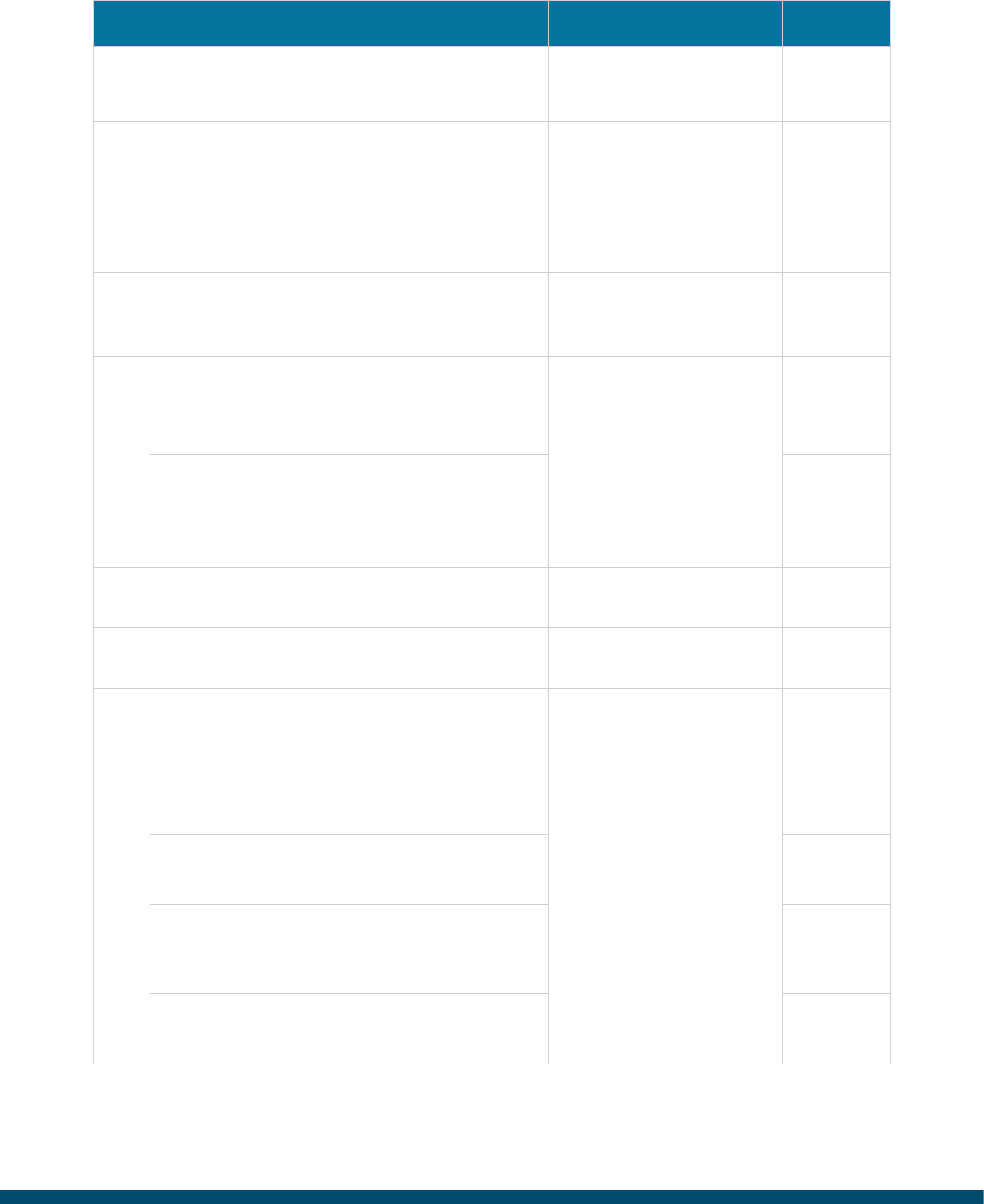

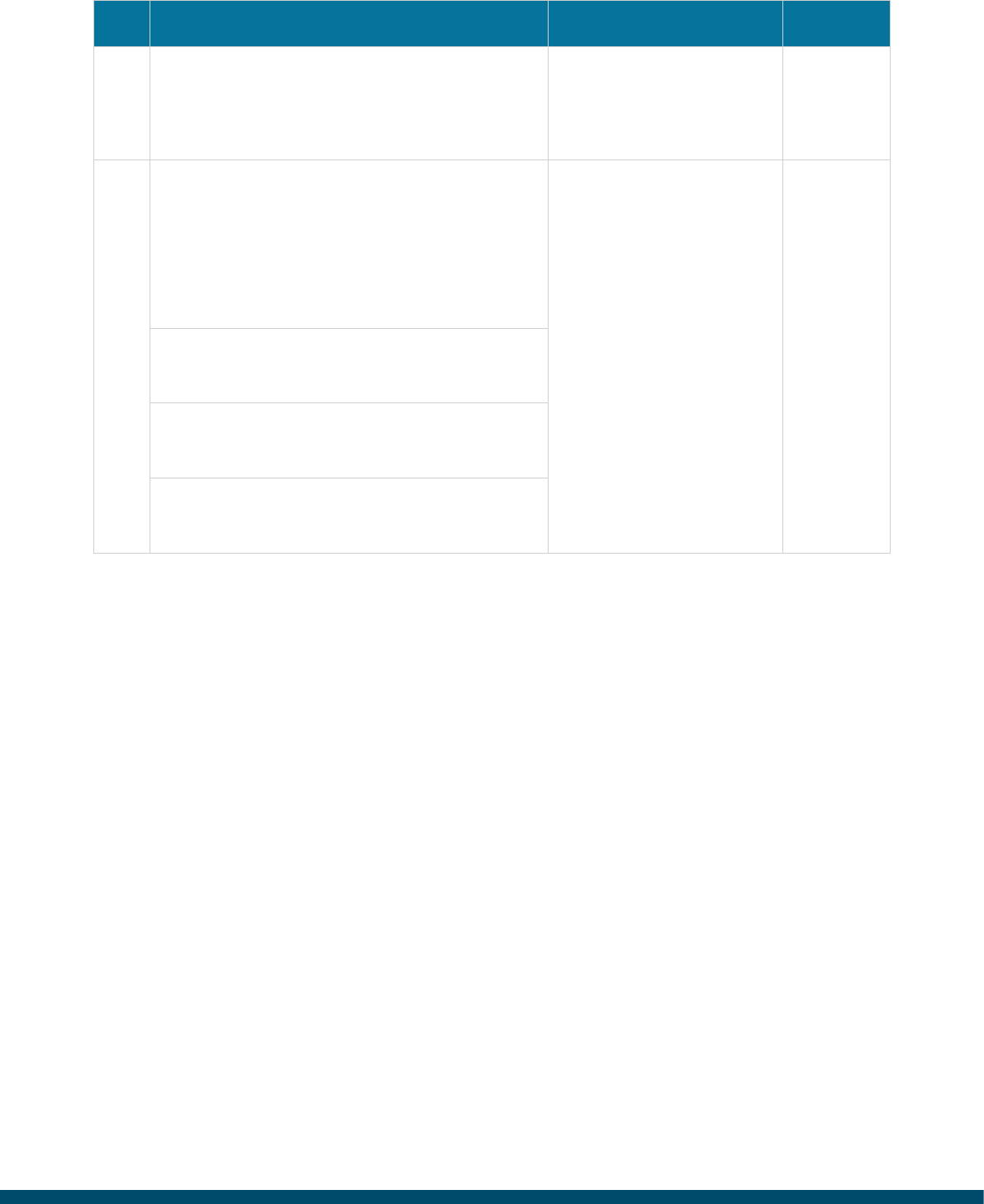

17

# Recommendation Action Guidance

1.2.4 Assess formal RTF communications training and assessment

for drivers and other personnel who operate on or near the

runway.

Aerodrome Operator (lead),

Air Navigation Service Provider

(support).

Appendix C

Appendix L

1.2.5 Assess the procedure for those occasions where manoeu-

vring area drivers become uncertain of their position on the

manoeuvring area.

Aerodrome Operator(lead),

Air Navigation Service Provider

(support).

Appendix C

1.2.6 Promote the adoption of ‘sterile cab’ procedures to improve

communications when on the manoeuvring area.

Aerodrome Operator(lead),

Air Navigation Service Provider

(support).

Appendix C

1.2.7 Assess the implementation of the ICAO standard naming

convention for the manoeuvring area to eliminate ground

navigation error and communication confusion.

Aerodrome Operator (lead),

Air Navigation Service Provider

(support).

Appendix K

1.2.8 a.

Ensure all vehicles on the manoeuvring area are in radio

contact with the appropriate Air Traffic Control service, i.e.

ground and/or the tower either directly or through an escort

Regulator,

Aerodrome Operator (lead),

Air Navigation Service Provider

(support).

Appendix A

Appendix C

b.

Assess the numbering policy for aerodrome vehicles and

consider assignment of unique numbers or airside identifica-

tion call signs for each airside vehicle (to reduce the risk of

vehicle related call sign confusion).

Appendix A

Appendix C

1.2.9 Ensure all manoeuvring area vehicle drivers are briefed at the

start of a shift.

Aerodrome Operator. Appendix C

Appendix L

1.2.10 Enable the tracking of vehicle movements on the manoeu-

vring area when possible.

Aerodrome Operator,

Air Navigation Service Provider.

Appendix M

1.2.11 Aerodrome Operators, in conjunction with ANSPs, should

review procedures for runway inspections.

This should include:

a.

Carrying out runway inspections in the opposite direction to

runway movements.

Aerodrome Operator,

Air Navigation Service Provider,

Regulator.

Appendix L

b.

Measures to ensure that uni-directional lighting is inspected

effectively.

Appendix C

c.

Introducing procedures to increase situational awareness (of

ATC and drivers) when vehicles occupy a runway (e.g. Vehicle

‘Operations Normal’ calls to ATC).

Appendix E

d.

Temporarily suspending operations to allow a full runway

inspection to be carried out without interruption.

Appendix L

18

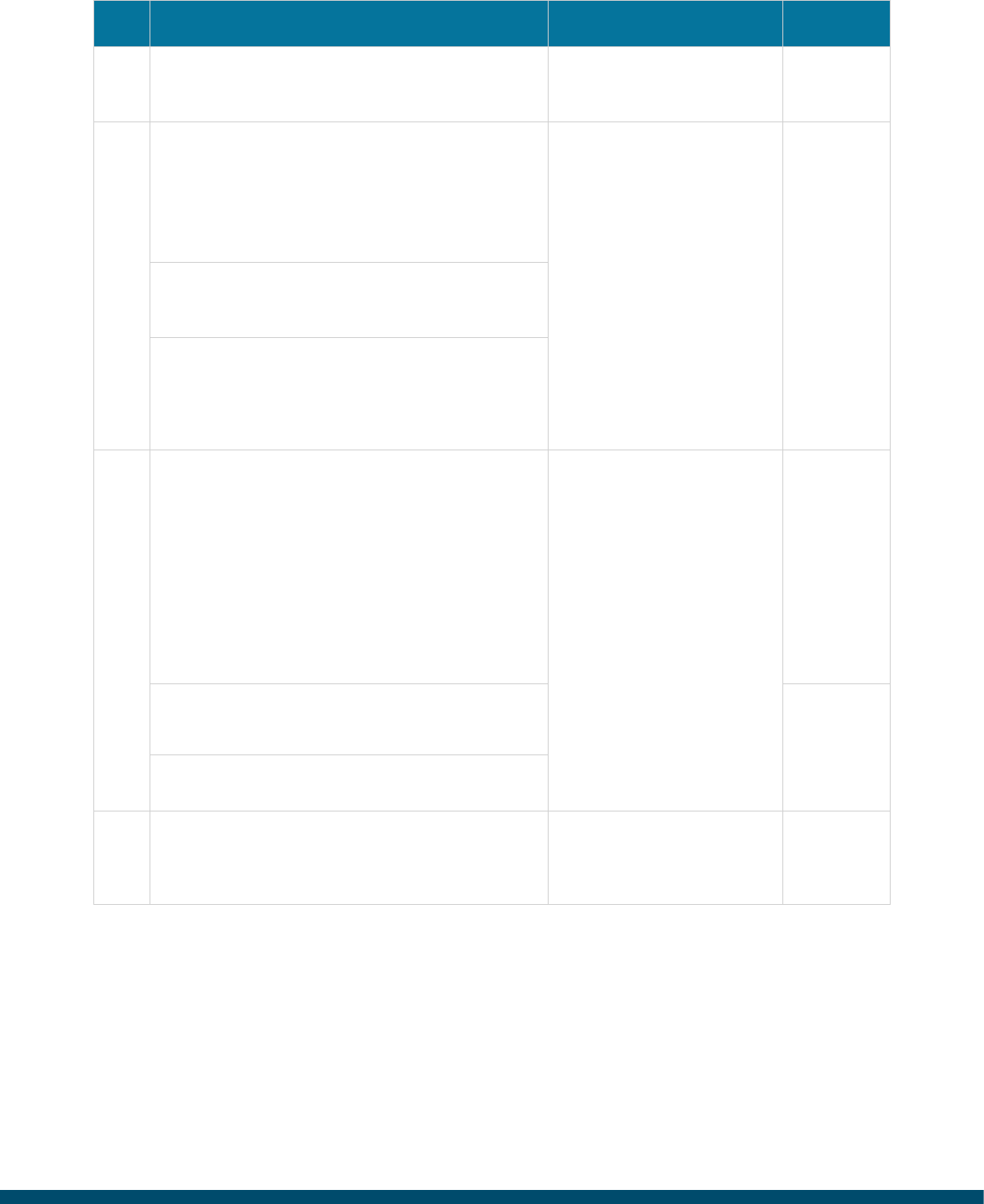

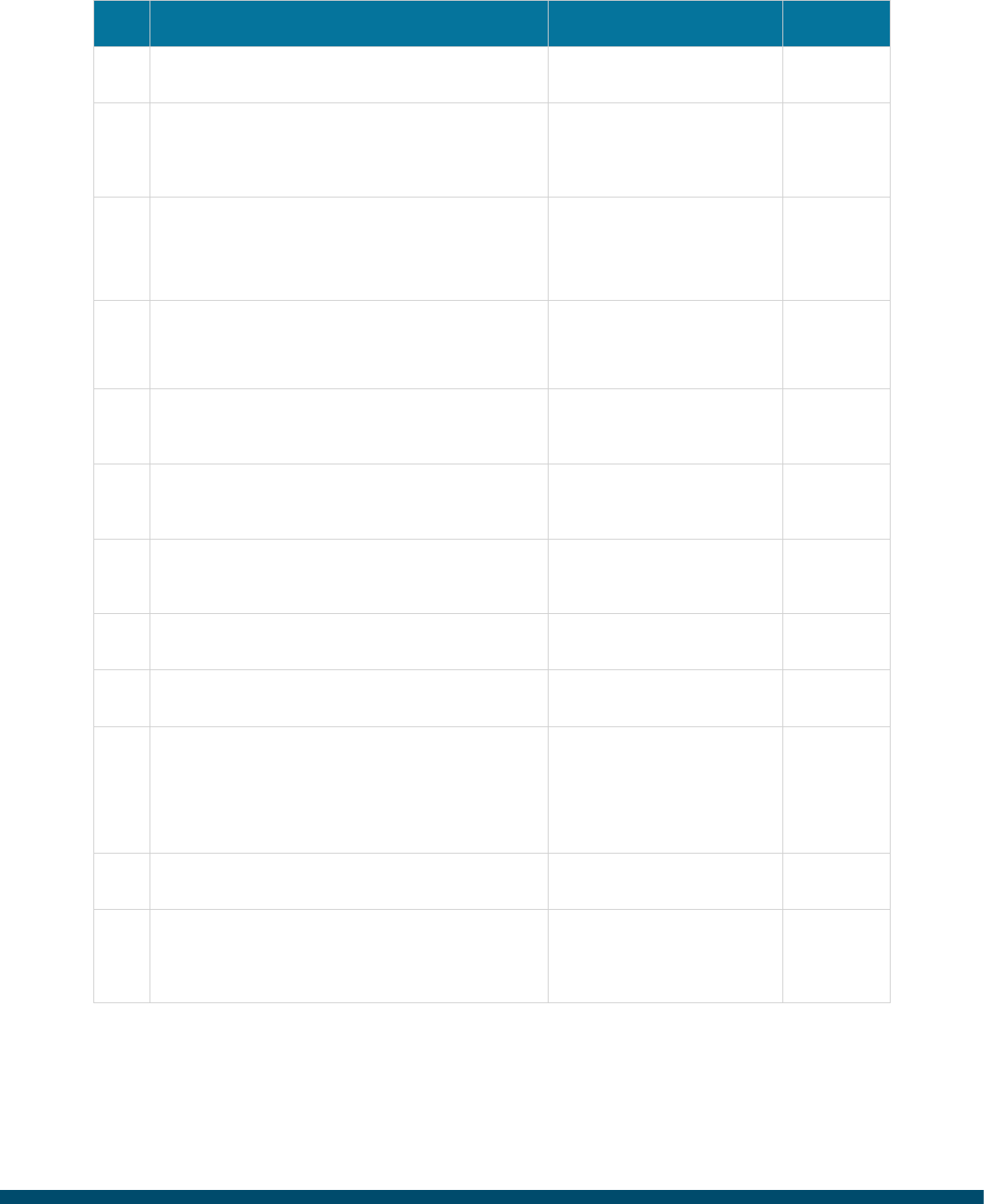

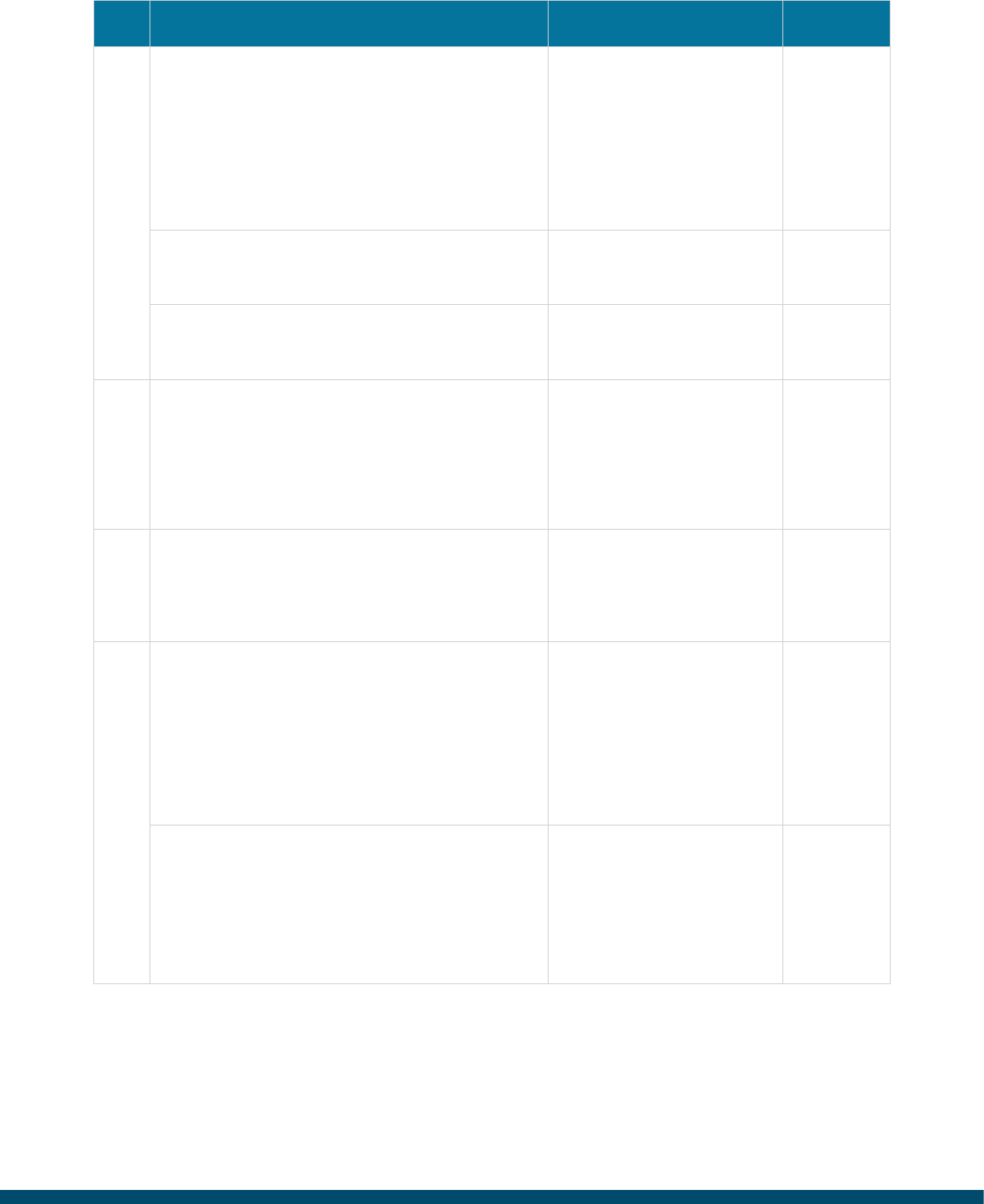

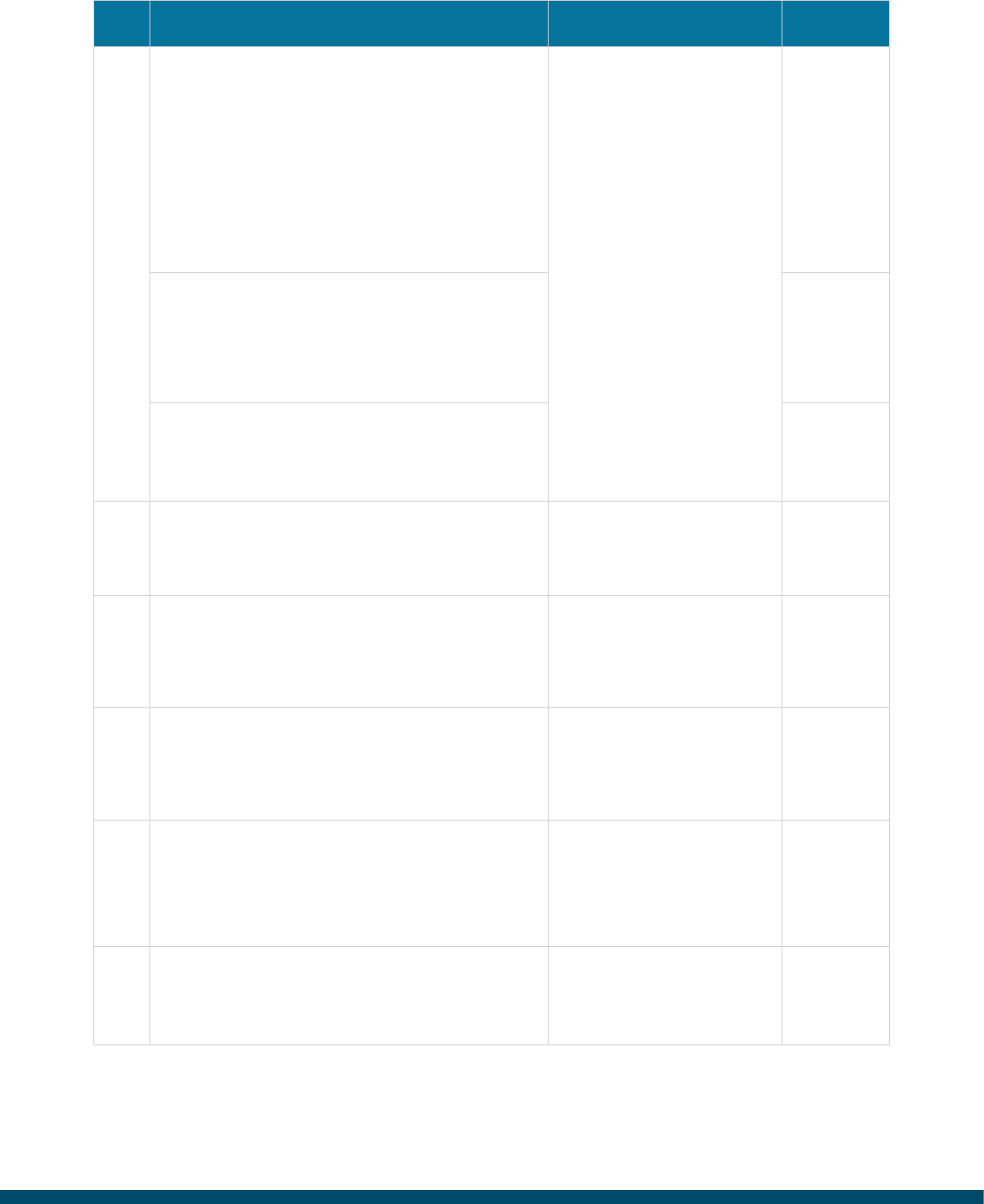

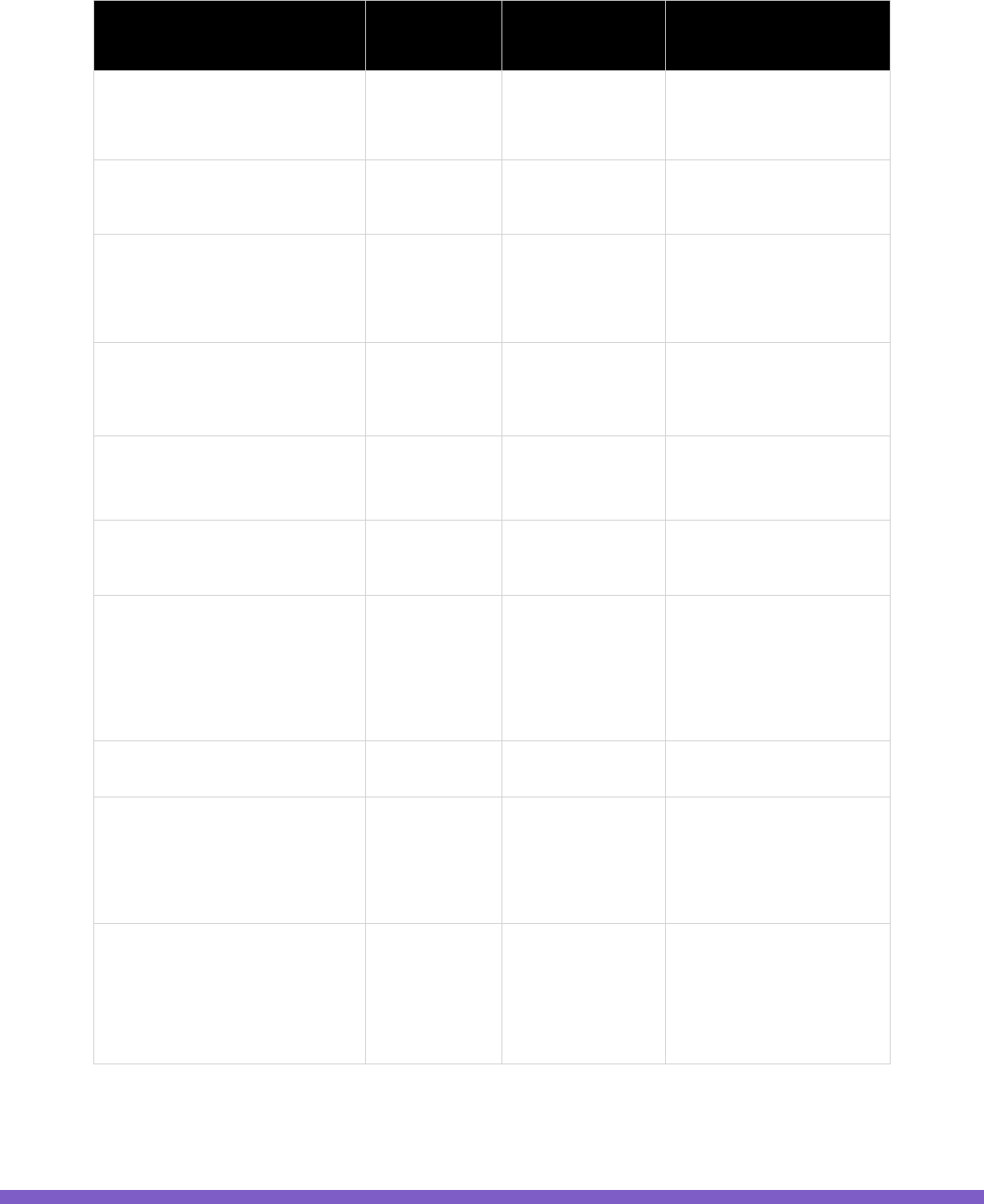

# Recommendation Action Guidance

1.2.12 New aerodrome infrastructure and changes to existing infra-

structure should be designed to reduce the likelihood

of runway incursions.

Aerodrome Operator. Appendix C

Appendix E

Appendix L

1.2.13 Working with ANSPs, avoid infringing lines of sight from the

air traffic control tower:

a.

Assess visibility restrictions from the tower, which have a

potential impact on the ability to see the manoeuvring area

especially critical areas such as runway entry points.

Aerodrome Operator,

Air Navigation Service Provider

Appendix E

Appendix H

b.

Consider short term safety actions such as dissemination of

this information as appropriate.

c.

Identify longer term improvement where possible and

develop appropriate mitigation, procedures, technology or

re-positioning of the facility to ensure the best solution pos-

sible within the limitations of the airport layout.

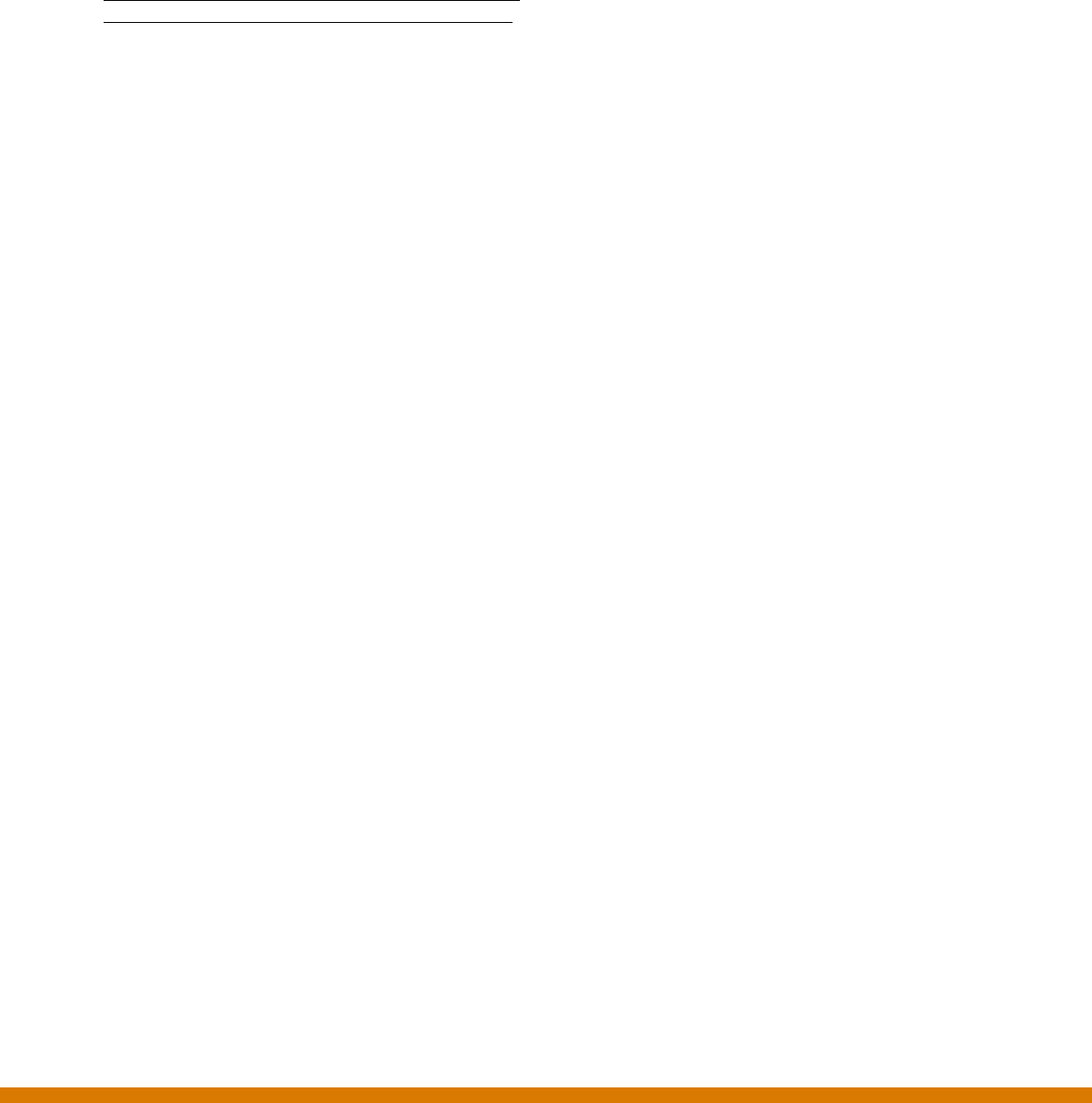

1.2.14 Regularly assess the operational use of aerodrome ground

lighting e.g. stop bars, to ensure a robust policy to protect

the runway from the incorrect presence of traffic:

a.

Safety studies have demonstrated that the use of H24 stop

bars can be an effective RI prevention barrier.

Therefore, Aerodrome Operator should, with ANSPs, consider

the implementation of H24 stop bars at all runway holding

points or other lighting systems providing an equivalent

level of safety (e.g. Autonomous Runway Incursion Warning

Systems (ARIWS)) at all runway holding positions.

Aerodrome Operator,

Air Navigation Service Provider,

Regulator.

Appendix E

Appendix J

b.

Assess the need for elevated stop bars to improve stop bar

conspicuity

Appendix E

c.

Consider use of LED technology to improve stop bar clarity.

1.2.15 Aerodrome Operators, in cooperation with ANSPs, should

implement procedures in line with Standardised European

Rules of the Air (SERA) in case of stop bar unserviceability.

Aerodrome Operator,

Air Navigation Service Provider.

Appendix E

Appendix J

19

# Recommendation Action Guidance

1.2.16 a.

The design of closely spaced multiple parallel runway hold-

ing positons on the same taxiway should be avoided.

Aerodrome Operator

Appendix K

b.

Where a. above cannot be followed, the holding positions

should be clearly segregated.

1.2.17 a.

Aerodrome Operators, in cooperation with ANSPs, should

identify the Protected Area for each runway and produce an

Aerodrome Protected Area chart/map.

Aerodrome Operator,

Air Navigation Service Provider,

Regulator.

Appendix C

Appendix M

b.

Ensure that the Protected Area map is used in manoeuvring

area driver training and is present in all vehicles that are driv-

ing on the manoeuvring area.

Appendix C

Appendix L

Appendix M

20

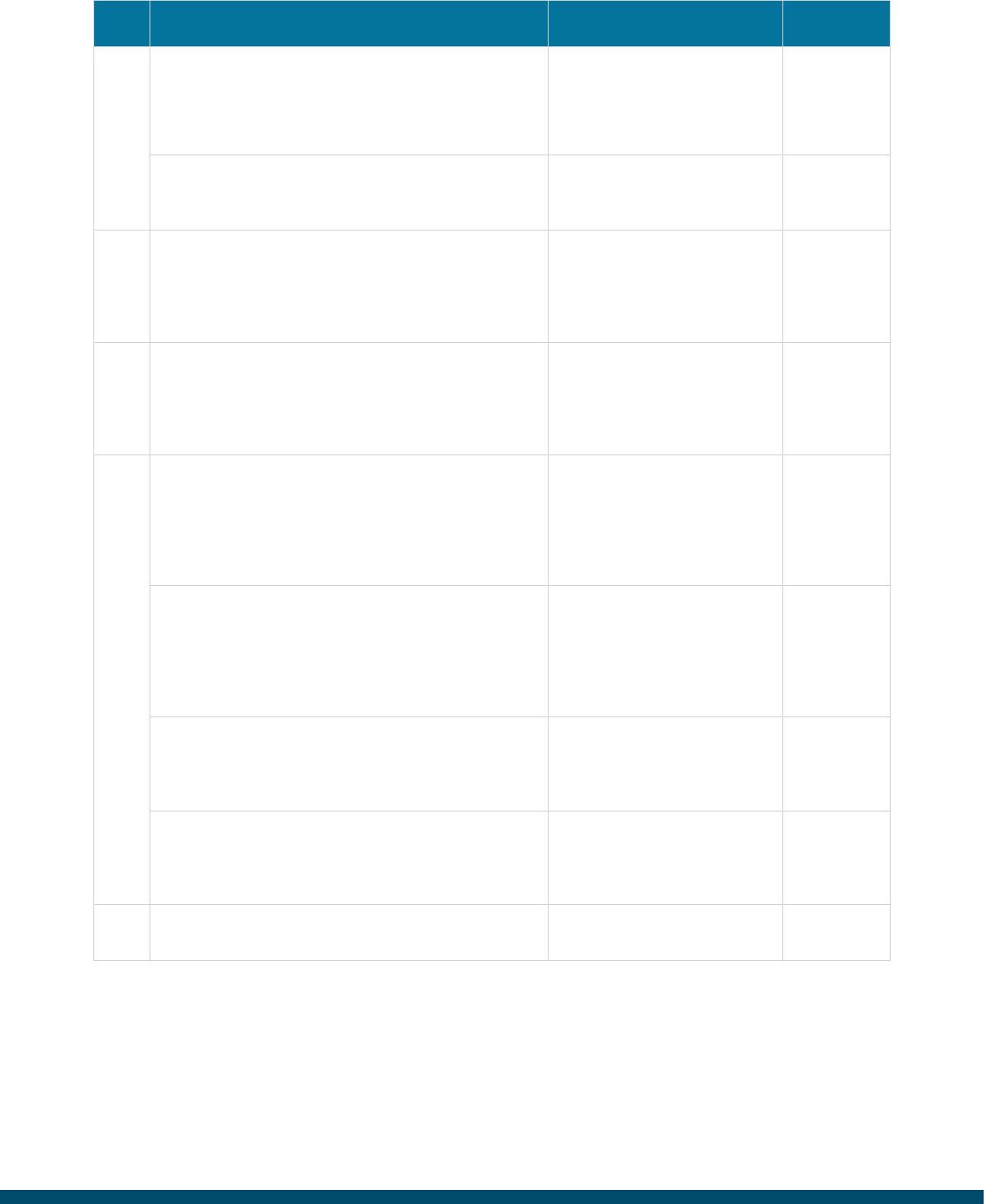

1.3 COMMUNICATIONS

# Recommendation Action Guidance

1.3.1 a.

To avoid the possibility of call sign confusion, implement the

use of full aircraft or vehicle call signs for all communications

concerning runway operations

Air Navigation Service Provider

(lead),

Aircraft Operator (lead),

Aerodrome Operator (lead).

Appendix A

Appendix E

b.

To avoid call sign confusion at aerodromes, implement the

introduction of discrete RTF call signs to manoeuvring area

vehicles.

Aerodrome Operator (lead),

Air Navigation Service Provider

(support).

Appendix E

1.3.2 Implement, monitor and ensure the use of standard phrase-

ologies as applicable:

EU: SERA Part C AMC

ICAO: Doc. 4444, PANS-ATM

Air Navigation Service Provider

(lead),

Aircraft Operator (lead),

Aerodrome Operator (lead).

Appendix A

Appendix B

Appendix E

Appendix L

1.3.3 Implement, monitor and ensure the use of the readback

procedure (also applicable to manoeuvring area drivers and

other personnel who operate on the manoeuvring area).

Air Navigation Service Provider

(lead),

Aircraft Operator (lead),

Aerodrome Operator (lead).

Appendix A

Appendix C

Appendix D

Appendix E

1.3.4 Where practicable, improve situational awareness by con-

ducting all communications associated with runway opera-

tions using aviation English.

Air Navigation Service Provider

(lead),

Aircraft Operator (lead),

Aerodrome Operator (lead).

Appendix A

Appendix C

Appendix D

Appendix E

1.3.5 When practicable, improve situational awareness, by imple-

menting procedures whereby all communications associated

with runway operations are on a common or cross-coupled

frequency.

Air Navigation Service Provider

(lead).

Appendix A

Appendix C

Appendix E

1.3.6 Consider regular evaluation of radio telephony practices,

assessing elements such as frequency loading and use of

EU/ICAO compliant phraseology.

Air Navigation Service Provider,

Aircraft Operator,

Aerodrome Operator.

Appendix A

Appendix B

Appendix E

1.3.7 If conditional clearances are used in accordance with ICAO

provisions, ensure a policy and robust procedures are

developed and implemented.

Air Navigation Service Provider. Appendix A

Appendix E

1.3.8 ANSPs and Aerodrome Operators should implement

procedures that ensure significant aerodrome information

which may affect operations on or near the runway, in

addition to that found in NOTAMS and on the ATIS, should be

provided to manoeuvring area drivers and pilots ‘real-time’

using radio communication.

Air Navigation Service Provider,

Aircraft Operator,

Aerodrome Operator.

Appendix C

Appendix E

Appendix H

21

1.4 AIRCRAFT OPERATOR

# Recommendation Action Guidance

1.4.1 Provide training and assessment for pilots regarding

Aerodrome signage, markings and lighting.

Aircraft Operator (lead). Appendix D

1.4.2 Pilots shall not cross illuminated red stop bars when lining-up

or crossing a runway (or on a taxiway where placed), unless

contingency procedures are in force, e.g. to cover cases

where the stop bars or controls are unserviceable.

Aircraft Operator. Appendix A

Appendix D

Appendix J

1.4.3 Ensure that flight deck procedures contain a requirement for

explicit clearances to cross any runway.

Guidance Note:

Includes non-active runways.

Aircraft Operator. Appendix A

1.4.4 Flight Crew should not enter a runway for departure if not

ready to take-off. Flight Crew must advise Air Traffic Control

on first contact with the Tower if additional time on the

runway is required for operational reasons.

Aircraft Operator,

Air Navigation Service Provider.

Appendix D

1.4.5 If received significantly early, flight crew should confirm with

ATC the line-up/take-off or crossing clearance when ap-

proaching the runway holding position.

Aircraft Operator,

Air Navigation Service Provider.

Appendix D

1.4.6 Flight crew should consider confirming landing clearance on

short final, if ATC issued it more than 5 nautical miles from

touch down.

Aircraft Operator,

Air Navigation Service Provider

Appendix D

1.4.7 Promote best practices in flight deck procedures while taxi-

ing and during final approach - to include the “Sterile flight

deck” concept.

IATA (lead),

ECA/IFALPA (support).

Appendix D

1.4.8 Promote best practices for pilots’ planning of ground

operations.

IATA (lead),

ECA/IFALPA (support).

Appendix D

1.4.9 Ensure a means to indicate receipt of landing / line-up / take

off / crossing clearances in the cockpit.

Airframe Manufacturer,

Aircraft Operator.

Appendix D

1.4.10 Pilots are advised to switch on forward facing lights when in

receipt of a take-off clearance and show forward facing lights

on the approach.

Guidance Note:

Global IFALPA policy

Aircraft Operator. Appendix D

1.4.11 Pilots must be made aware of current safety significant

airport information.

Aircraft Operator. Appendix H

1.4.12 During taxi for departure or during approach, pilots should

not accept a runway change proposal if time to

re-programme the FMS / re-brief is not sufficient.

This includes a change of departure intersection.

Aircraft Operator,

Air Navigation Service Provider.

Appendix D

22

# Recommendation Action Guidance

1.4.13 If Pilots have any doubt as to their exact position on the

surface of an aerodrome, they should contact Air Traffic

Control and follow the associated ICAO procedure (ICAO Doc.

4444, PANS-ATM).

Aircraft Operator. Appendix D

1.4.14 A pilot should avoid being “head-down” to ensure a

continuous external watch is maintained whilst taxiing.

Aircraft Operator. Appendix D

1.4.15 If there is any doubt when receiving a clearance or

instruction, clarification should be requested immediately

from Air Traffic Control.

Aircraft Operator. Appendix A

Appendix D

1.4.16 Aerodrome charts or an equivalent electronic device should

be displayed on the flight deck during taxi. This includes

when operating at the home aerodrome.

Aircraft Operator. Appendix D

1.4.17 Avoid accepting rapid exit taxiways or angled taxiways for

line-up that limits the ability of the Flight crew to see the

runway threshold or the final approach area.

Aircraft Operator. Appendix D

1.4.18 Ensure that crews are aware of the significance of red lights

(e.g. stop bars and other red lights) used in line with alerting

systems to prevent incorrect entry onto a runway and to

enhance situational awareness.

Aircraft Operator. Appendix J

1.4.19 A pilot shall only apply Engine-Out–Taxi (EOT) procedure

after careful consideration of local and operational

circumstances so as to avoid a conflict with sterile cockpit

procedures.

Aircraft Operator. Appendix D

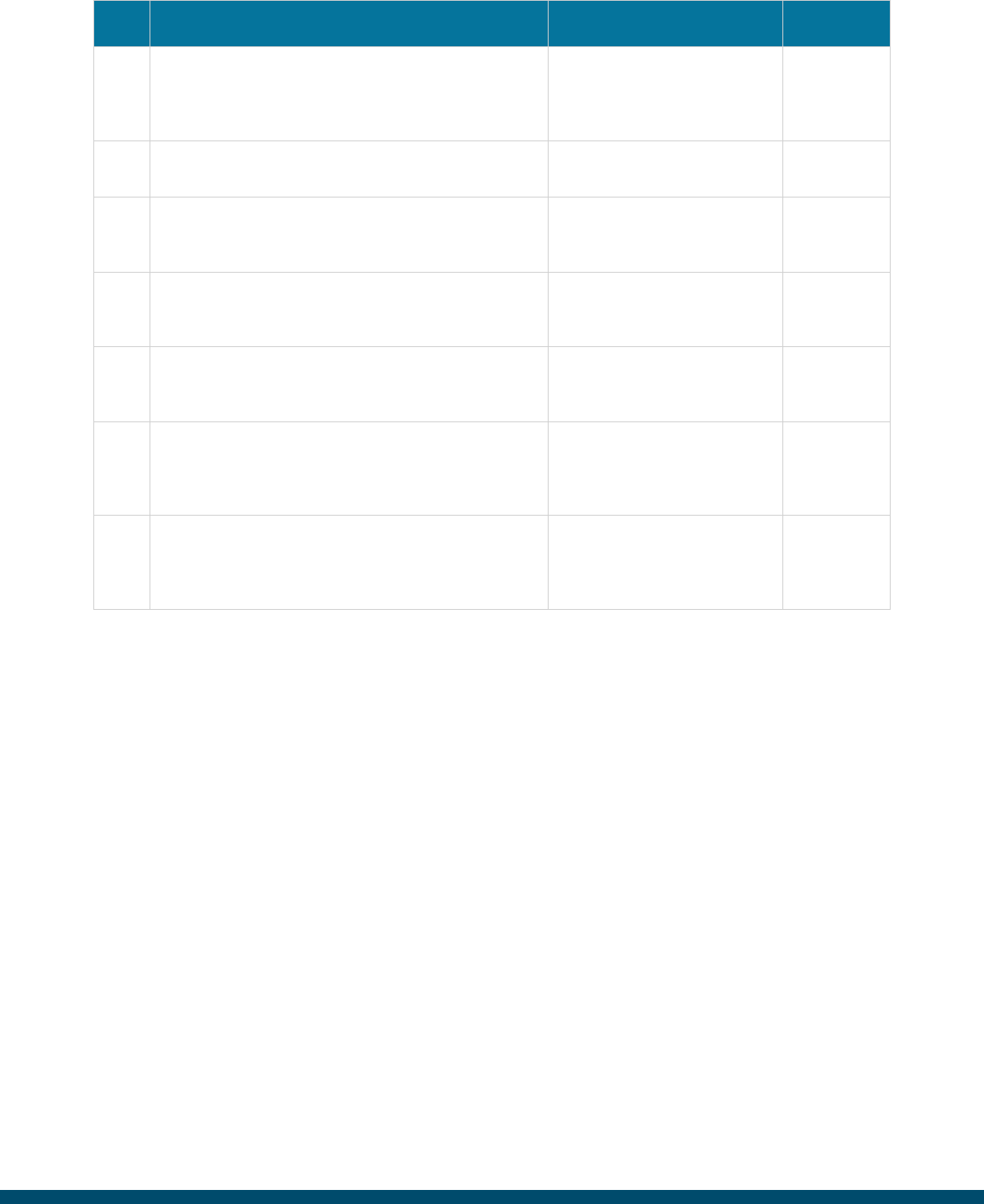

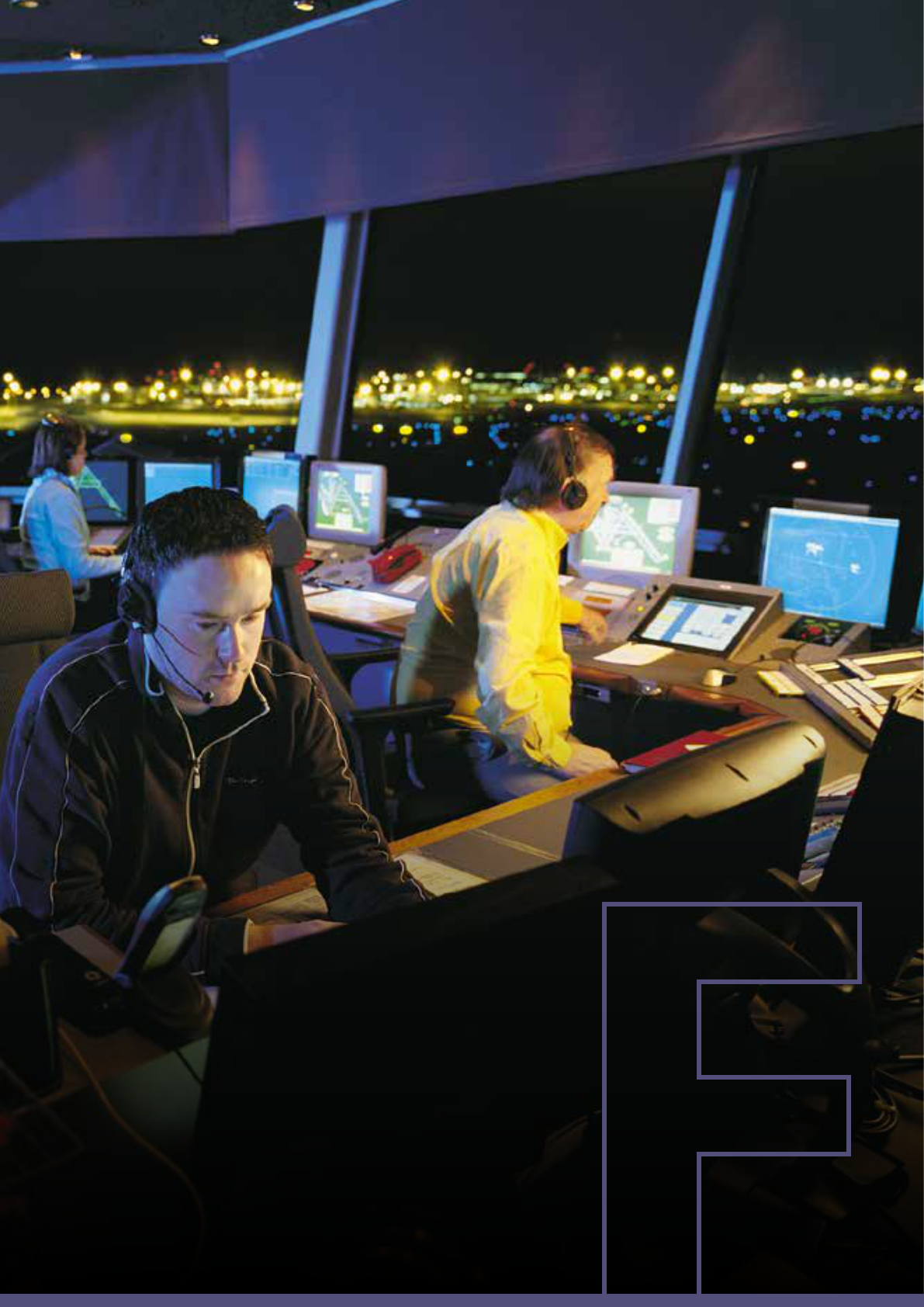

1.5 AIR NAVIGATION SERVICE PROVIDER

# Recommendation Action Guidance

1.5.1 ANSPs shall ensure that runway safety issues are included

in initial and refresher training and briefings for Air Traffic

Control staff.

Air Navigation Service Provider. Appendix E

1.5.2 ANSPs shall implement, update or highlight existing pro-

cedures that assist air traffic controllers, pilots and vehicle

drivers to maintain good situational awareness. Procedures

should also support pilots to maintain a sterile cockpit envi-

ronment and maintain situational awareness whilst taxying

or during critical stages of operation.`

Actions include:

a.

Ensuring that Air Traffic Control communication messages

are not overly long or complex.

Air Navigation Service Provider. Appendix E

b.

Indicating the ultimate clearance limit (e.g. the runway

holding position or intermediate holding position) and, in

case of complex /overlong taxi route, use progressive taxi

instructions to reduce pilot/vehicle driver workload and the

potential for confusion.

Air Navigation Service Provider. Appendix E

c.

It is strongly advised to develop and utilize standard taxi

routes and clear standard route designators to minimise the

potential for confusion, on or near the runway.

Air Navigation Service Provider. Appendix E

d.

Whenever possible, pass en-route clearances prior to taxi

and, in order to avoid distractions during taxi, consider the

passing of revisions to en-route clearances whilst an aircraft

is stopped.

Air Navigation Service Provider. Appendix E

e.

When an aircraft is at a holding position or on the runway,

ATC should always use the phrase: “HOLD POSITION” before

passing a revised clearance.

Air Navigation Service Provider. Appendix E

f.

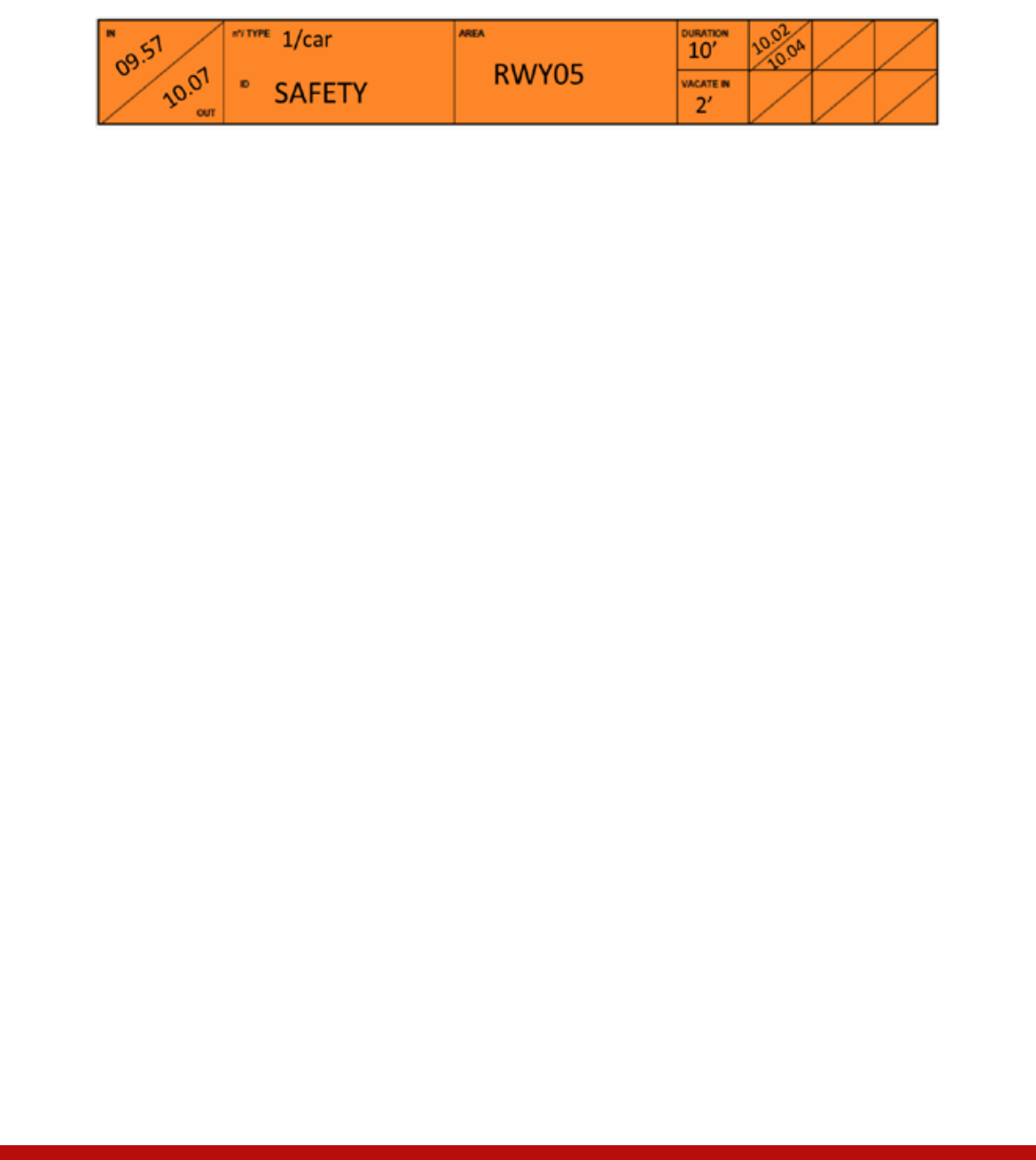

Record and track vehicles entering the manoeuvring area

through the use of vehicle progress strips.

Air Navigation Service Provider. Appendix E

g.

When planning a runway change for departing or arriving

traffic, consider the time a pilot will require to prepare/re-

brief.

Air Navigation Service Provider. Appendix E

h.

Issue line-up and/or take-off or crossing clearance only when

the aircraft is at or approaching the runway holding position.

Air Navigation Service Provider. Appendix E

i.

Do not issue a line-up clearance if the pilot has reported the

aircraft is not ready to depart.

Air Navigation Service Provider. Appendix E

23

24

# Recommendation Action Guidance

j.

Do not issue a line-up clearance if the aircraft is expected to

wait on the runway for more than 90 seconds before being

able to issue the take-off clearance.

Air Navigation Service Provider. Appendix E

k.

Do not use angled taxiways for entering the runway that limit

the ability of the flight crew to see the runway threshold or

the final approach area.

Guidance Note:

Consider to mandate the application in case of multiple or

intersection departures.

Air Navigation Service Provider. Appendix E

l.

Avoid issuing premature landing clearance.

Air Navigation Service Provider. Appendix E

1.5.3 ANSPs should assess the current procedures regarding

runway occupancy status and support the implementation of

memory aids considering also the availability of new/emerg-

ing technologies.

Air Navigation Service Provider. Appendix E

1.5.4 ANSPs should consider the implementation of emerging

technology that can improve situational awareness and im-

prove safety nets. This could include the implementation of

enhanced A-SMGCS functionalities or alternative surveillance

technologies.

Air Navigation Service Provider. Appendix E

Appendix N

1.5.5 ANSPs, in conjunction with the Aerodrome Operator, shall

implement procedures for when an aircraft or vehicle be-

comes lost or uncertain of its position on the manoeuvring

area. It is recommended that these procedures are reviewed

and tested on a regular basis.

Air Navigation Service Provider. Appendix C

Appendix E

Appendix L

1.5.6 ANSPs, in conjunction with the Aerodrome Operator, should

regularly review procedures for runway inspections. This

should include the evaluation of:

a.

Carrying out routine runway inspections in the opposite

direction to runway movements.

Air Navigation Service Provider. Appendix C

Appendix E

Appendix L

b.

Implementing procedures to increase overall situational

awareness when vehicles occupy a runway (e.g. ‘Vehicle

Operation Normal’ calls.

Air Navigation Service Provider. Appendix C

Appendix E

Appendix L

25

# Recommendation Action Guidance

1.5.7 Safety studies have demonstrated that the misapplication

and misinterpretation of conditional clearances can be a

contributing factor in runway incursions.

Therefore ANSPs should:

a.

Assess conditional clearance operational procedures

and practices.

Air Navigation Service Provider. Appendix A

Appendix E

b.

Consider if the operational use of conditional clearances can

be reduced or removed at a specific aerodrome.

Air Navigation Service Provider. Appendix A

Appendix E

c.

Raise awareness to ATC staff about the correct use of condi-

tional clearances and potential risks.

Air Navigation Service Provider. Appendix E

1.5.8 ATC procedures shall contain a requirement to issue an

explicit clearance, including the runway designator, when

authorizing a runway entry, runway crossing or hold short of

any runway.

Guidance Note:

Includes non-active runways.

Air Navigation Service Provider. Appendix E

Appendix N

1.5.9 ANSPs should review, on a regular basis, runway capacity

enhancing procedures when used either individually or in

combination (intersection departures, multiple line-up, con-

ditional clearances etc.) to identify any potential hazards and,

if necessary, develop appropriate mitigation strategies.

Air Navigation Service Provider. Appendix B

Appendix E

1.5.10 ANSPs should regularly assess the operational use of aero-

drome ground lighting (e.g. stop bars, runway guard lights)

in line with the applicable EU/ICAO provisions, to ensure a

robust runway protection policy, and:

a.

Stop Bars at runway holding position must always be con-

trolled by the controller in charge of the runway operations

on that runway (Aerodrome controller).

Air Navigation Service Provider. Appendix E

Appendix J

b.

Safety studies have demonstrated that the use of H24 stop

bars may be an effective RI prevention barrier. Therefore,

considering local constraints and specificities, Aerodrome

Operators should, with ANSPs, consider the implementation

of H24 stop bars or other lighting systems providing an

equivalent level of safety (e.g. ARIWS) at all runway holding

positions.

Air Navigation Service Provider. Appendix E

Appendix J

26

# Recommendation Action Guidance

c.

ANSPs, in cooperation with Aerodrome Operators, should

implement procedures, in line with the applicable EU

Regulations and associated AMC and GM in case of stop bar

unserviceability.

Air Navigation Service Provider. Appendix E

Appendix J

d.

Aircraft or vehicles shall not be instructed to cross illuminat-

ed red stop bars unless contingency procedures are in force.

Air Navigation Service Provider. Appendix E

Appendix J

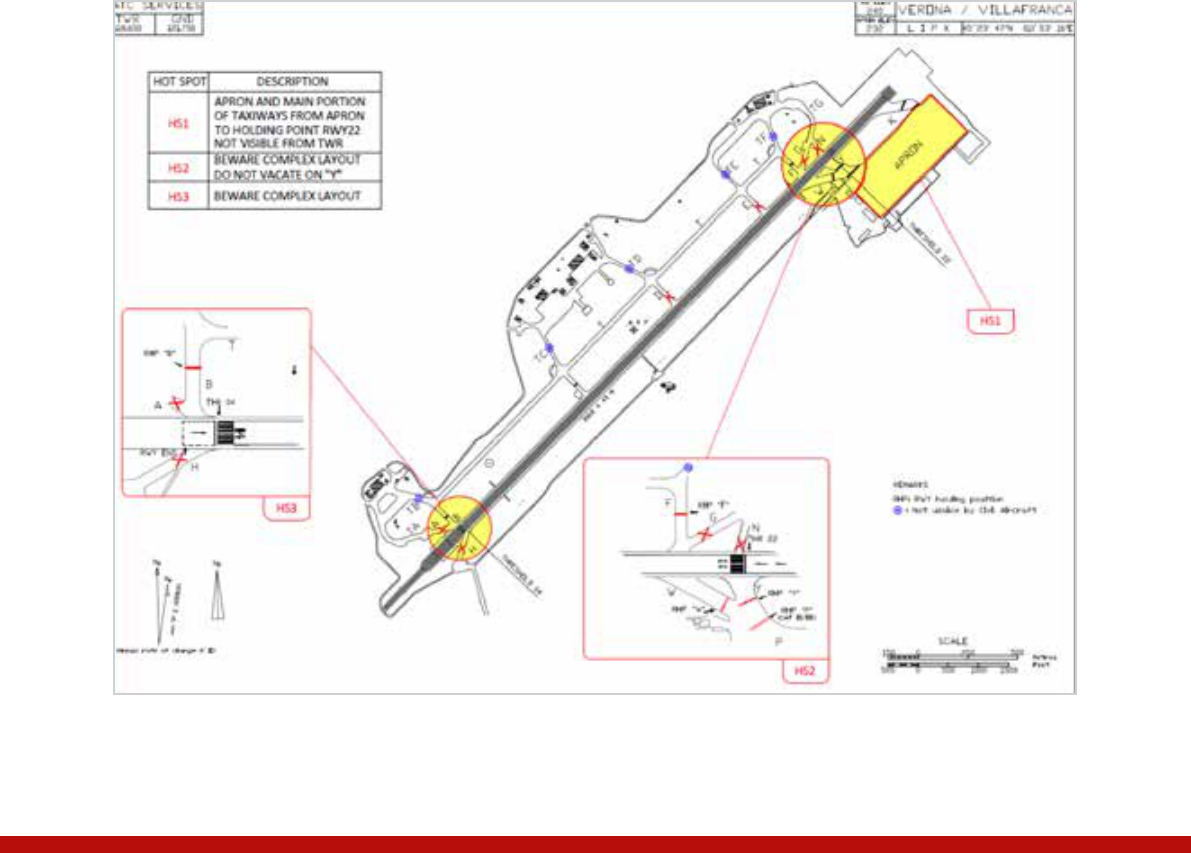

1.5.11 ANSPs should assess the sight lines from the Tower Visual

Control Room (VCR) and existing visibility restrictions which

have a potential impact on the ability to see the runway.

Disseminate information as appropriate (e.g. include on ap-

propriate AIP- A/D chart).

Air Navigation Service Provider. Appendix E

1.5.12 In case of infringement of the Tower VCR sight lines, ANSPs

should develop and implement short-term appropriate miti-

gations and identify longer term improvement, whenever

possible.

Air Navigation Service Provider,

Aerodrome Operator.

Appendix E

Appendix K

1.5.13 a.

ANSPs should regularly review Human Machine Interface

(HMI) effectiveness. Controller Working Position (CWP)

ergonomics and procedures shall promote and improve the

controller ‘visual scan’ of the manoeuvring area in all weather

conditions.

Air Navigation Service Provider,

Aerodrome Operator.

Appendix E

b.

Air traffic controllers shall perform a visual scan of the

entire runway and approach area in both directions before

issuing a clearance to enter the runway or landing. This

should primarily be by direct visual means, backed up by

surveillance equipment in poor visibility situations.

Air Navigation Service Provider. Appendix E

c.

ANSP shall develop procedures to ensure that, as far as

practicable, controllers are “heads-up” for a continuous watch

of aerodrome operations.

Air Navigation Service Provider. Appendix E

d.

Air traffic controllers should pay attention to aircraft ‘vacating’

runways in particular where the exit taxiway may lead

directly to another runway (crossing).

Air Navigation Service Provider. Appendix E

1.5.14 ANSPs should apply and actively encourage Team Resource

Management (TRM) principles in operations.

Air Navigation Service Provider. Appendix E

27

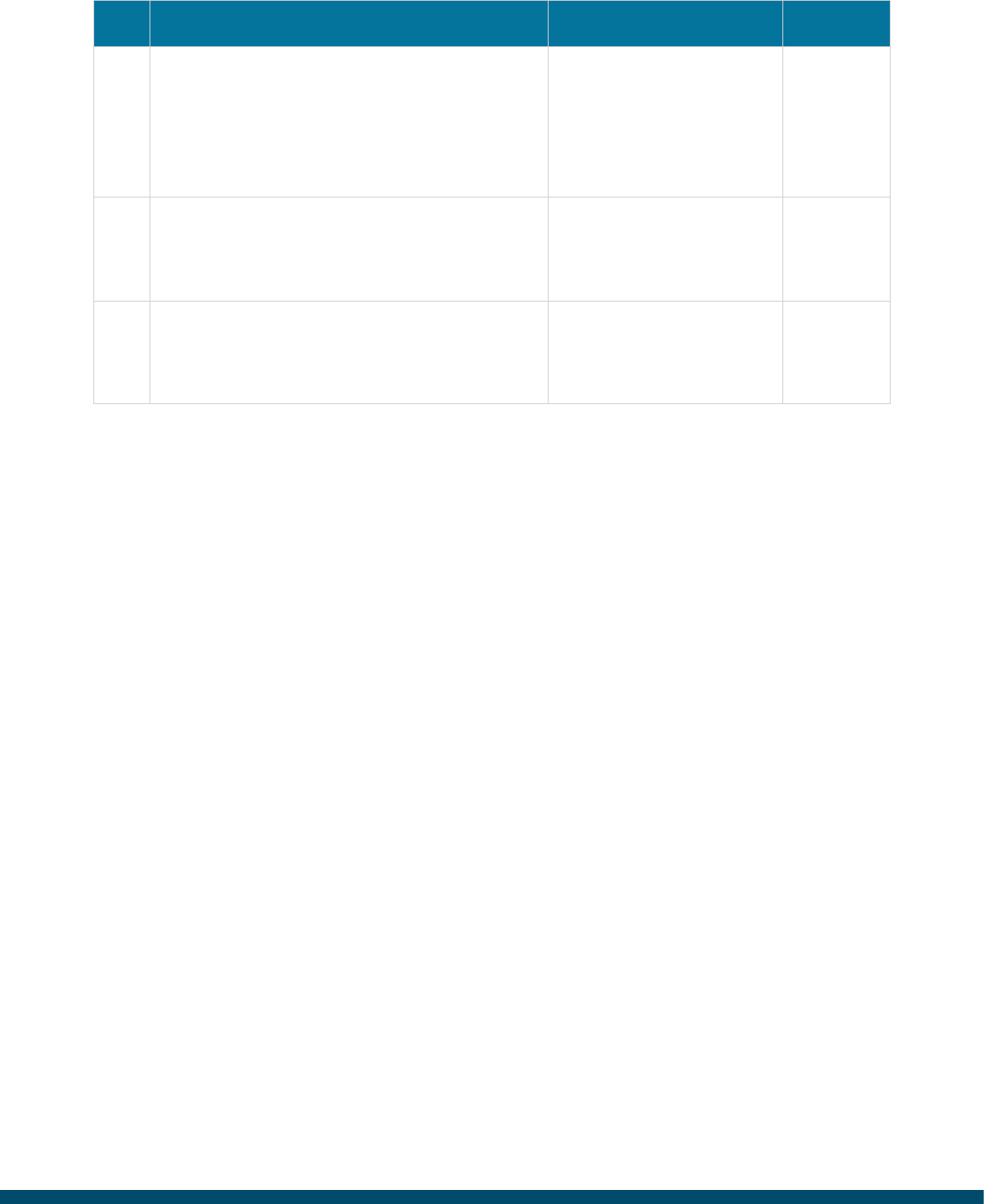

1.6 DATA COLLECTION AND LESSON SHARING

# Recommendation Action Guidance

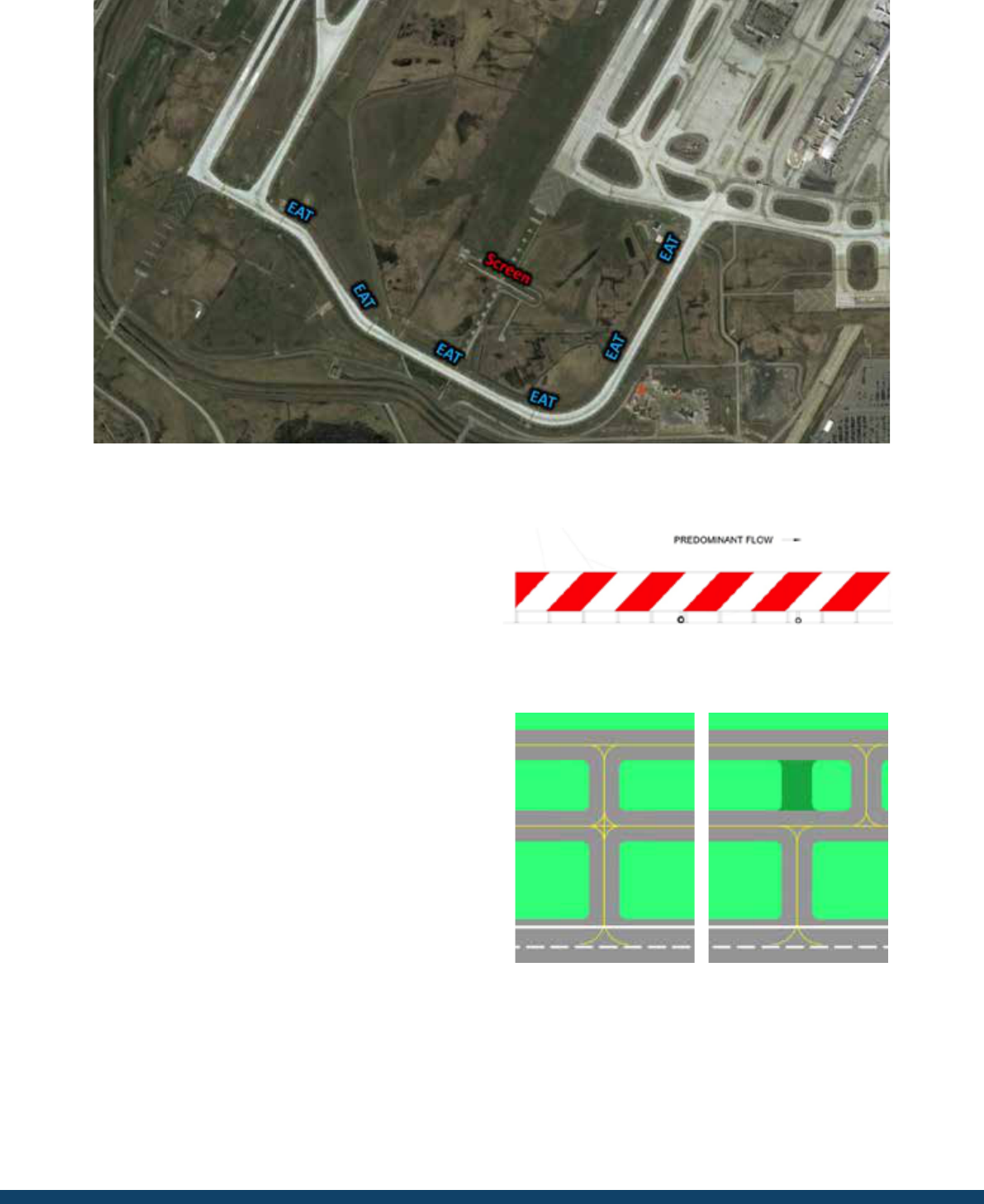

1.6.1 Review and promote the implementation of occurrence

reporting regimes and ensure their compatibility with ICAO,

EU and national provisions.

Regulator,

Air Navigation Service Provider,

Aircraft Operators,

Aerodrome Operators.

Appendix B

1.6.2 Disseminate de-identified information on actual runway

incursions locally to increase understanding of causal and

contributory factors to enhance lesson learning.

Regulator,

Aerodrome Operator,

Air Navigation Service Provider,

Aircraft Operator.

Appendix B

Note:

See also General Principle Recommendations 1.1.6a, 1.1.6b and 1.1.9.

28

1.7 REGULATORS

# Recommendation Action Guidance

1.7.1 Confirm that all infrastructure, practices and procedures

relating to runway operations are in compliance with EU

Regulations and, as applicable, any ICAO and/or national

provisions.

Regulator. Appendix J

Appendix K

Appendix L

1.7.2 Ensure the implementation of safety management systems

is in accordance with EU Regulations and, as applicable, any

ICAO and/or national standards.

Regulator. Appendix G

1.7.3 Ensure that safety assurance documentation for operational

systems (new and modified) demonstrates compliance with

regulatory and safety management system requirements. .

Regulator. Appendix G

1.7.4 Regulators should focus on runway safety in their oversight

activities e.g. preventing runway incursion risks.

Regulator. Appendix F

1.7.5 Ensure that Aerodrome Operators and Air Navigation Service

Providers regularly review the operational use of aeronautical

ground lighting e.g. stop bars, to ensure a robust policy to

protect the runway from the incorrect presence of traffic.

Guidance Note:

Aircraft operators should also be invited to review to provide

a wider perspective.

Air Navigation Service Provider,

Aerodrome Operator,

Aircraft Operator,

Regulator.

Appendix E

Appendix J

1.7.6 Ensure that the content of training materials for Pilots, Air

Traffic Controllers and Drivers working on the manoeuvring

area includes runway incursion prevention measures and

awareness.

Regulator. Appendix F

1.7.7 Ensure that environmental procedures e.g. noise mitigation

rules take due account of runway safety.

Guidance Note:

Those noise mitigation elements that could potentially

affect runway incursion/excursion risk include (but are not

limited to): Airfield design and alignment based on noise

consideration, noise preferred runway or runway operational

mode, time-based runway selection to share noise load,

runway specific curfews, arrival/departure curfews etc. which

may (for example) require additional backtrack, runway

crossings or other similar and otherwise avoidable risk.

Regulator.

Appendix B

29

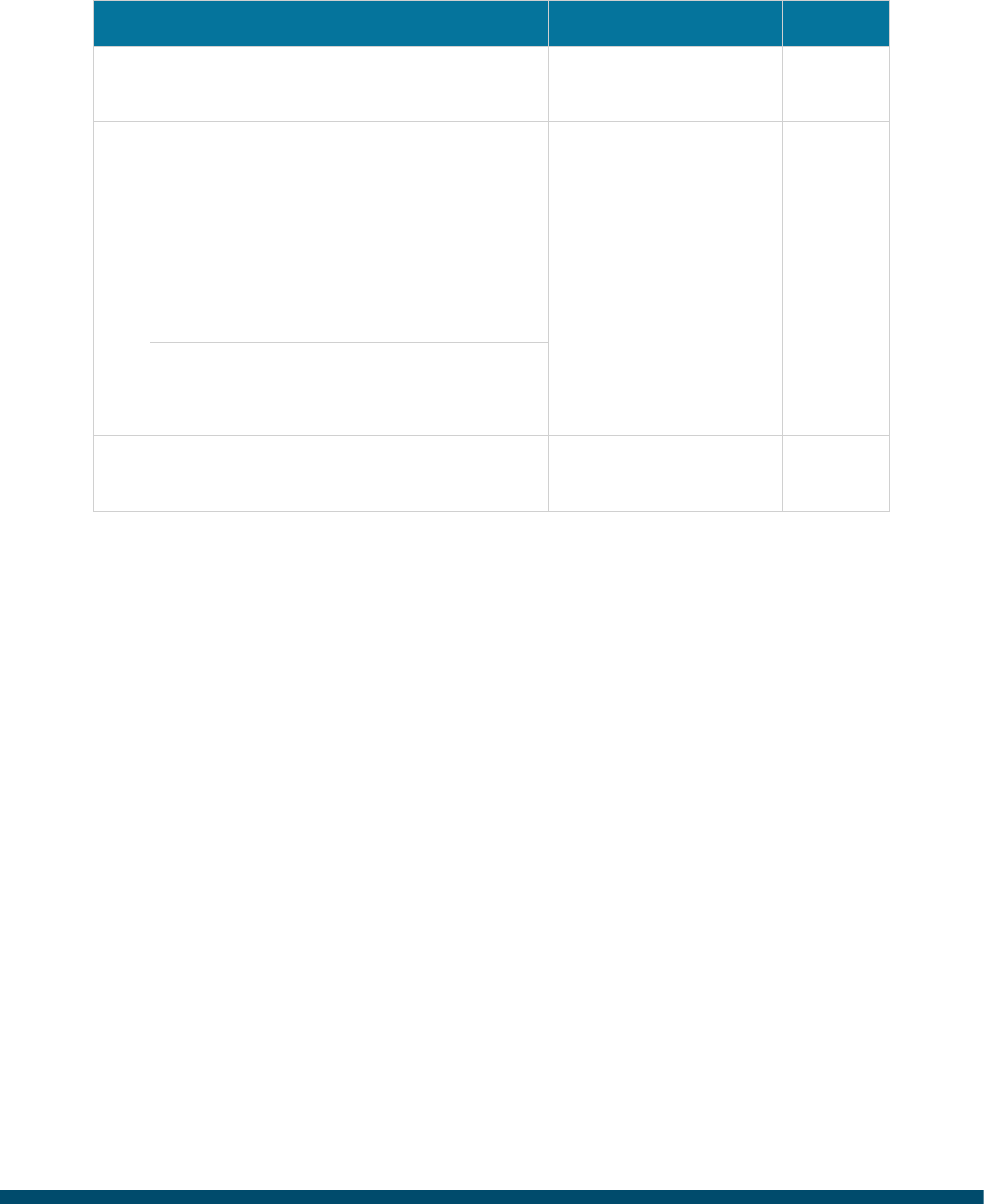

# Recommendation Action Guidance

1.7.8 Assess the performance of the change management process

for procedural and/or infrastructural changes on the ma-

noeuvring area.

Regulator. Appendix G

1.7.9 National agencies charged with the oversight of aviation

safety should consider how they discharge their

responsibilities for runway safety which may include:

a.

The establishment and coordination of a national/state

runway safety group that, inter alia, will address the

prevention of runway incursions and runway collision risk.

Regulator.

Appendix B

Appendix F

b.

Ensuring the prevention of runway incursions in national

runway safety plans/State Safety Plans.

c.

Supporting the state-wide promotion and coordinated

implementation of EAPPRI v3.0.

d.

Participating in aerodrome local Runway Safety Teams.

30

1.8 AERONAUTICAL INFORMATION MANAGEMENT AIM

# Recommendation Action Guidance

1.8.1 Ensure that the content of aeronautical information provided

is in accordance with the ICAO standards and recommended

practices and is up to date and relevant to the pilot.

a.

Information on aerodrome conditions should be simple to

understand and focused on what is operationally necessary

for the safety of flight, expressed in a standardised manner

on format and content. Content should be minimized in

volume as far as it does not compromise its efficiency and

comprehensiveness.

Air Navigation Service Provider,

Aeronautical Information Service

Provider,

Aerodrome operator, Regulator.

Appendix H

b.

Information on temporary changes to operating conditions

at the aerodrome should be optimized to increase the

situational awareness of the most critical changes. When

needed, an AIP Supplement with graphics and charts should

be published.

Appendix H

c.

For planned temporary changes, issuance of NOTAM with

short notice ahead of the effective date or non-AIRAC

publications should be avoided.

Appendix H

Appendix L

1.8.2 Data (DAT) providers of aeronautical data, flight manuals

and charts should establish a process with the Aeronautical

Information Service Provider, with the objective of ensuring

the accuracy, timeliness and integrity of the data.

Aeronautical Information

Service Provider,

Industry.

Appendix H

1.8.3 Ensure that the means and procedures are established at

aerodromes for the collection of post-flight information and

to allow users to provide feedback on the availability and

quality of aeronautical information, in accordance with ICAO

Annex 15 Aeronautical Information Services.

Aeronautical Information Service

Provider,

Aerodrome Operator,

Aircraft Operator,

EUROCONTROL.

Appendix H

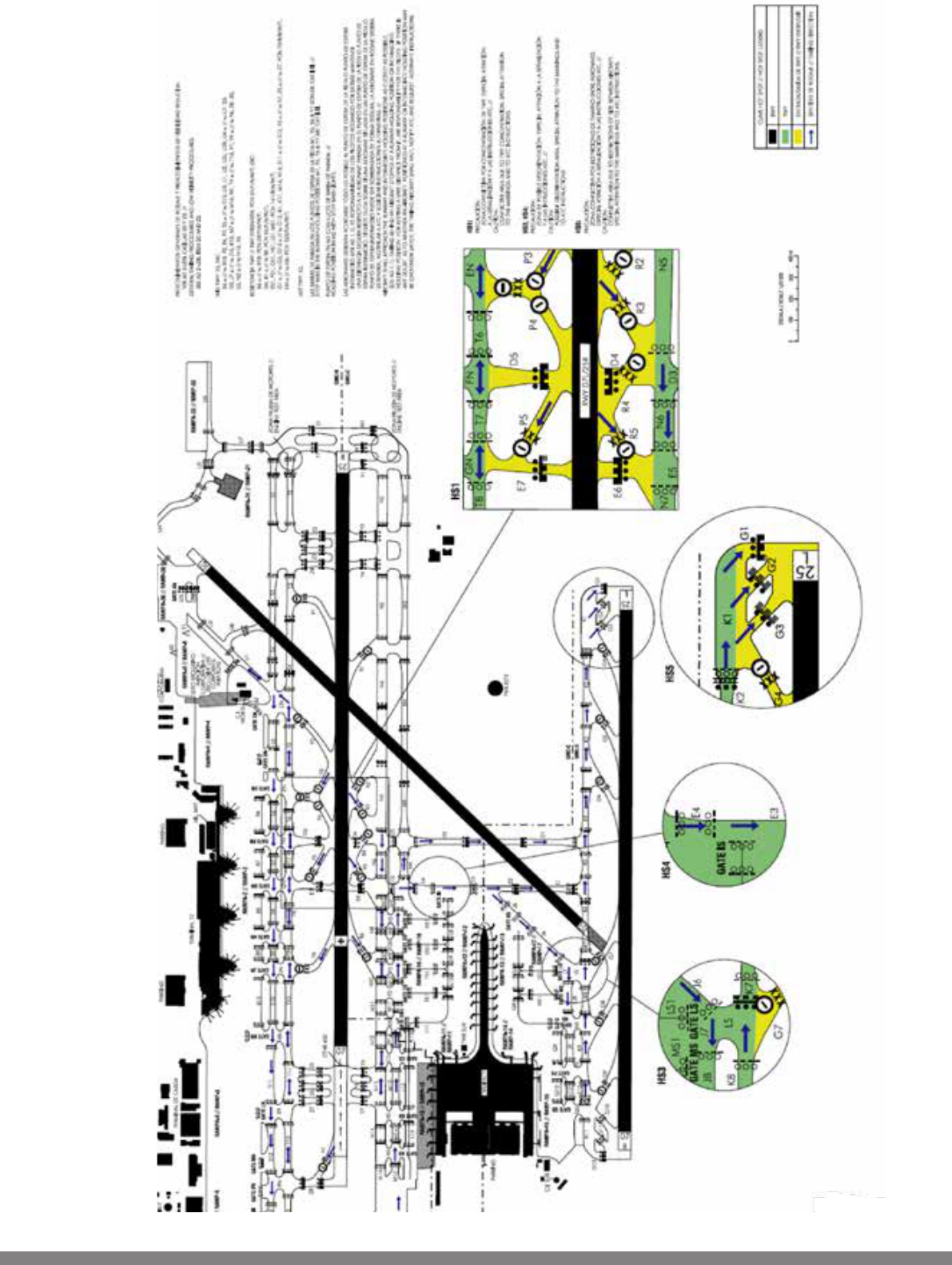

1.8.4 The ergonomics of aeronautical maps and charts and

relevant documentation should be improved to enhance

their readability and usability, and be in accordance with

relevant standards for aeronautical charts.

Air Navigation Service Provider,

Aeronautical Information Service

Provider,

Aerodrome Operator,

Aircraft Operator.

Appendix H

1.8.5 Move towards digital aeronautical information

management to provide and use high quality aeronautical

and aerodrome data in an interoperable exchange format.

Aerodrome Operator,

Air Navigation Service Provider,

Aeronautical Information Service

Provider,

Regulator,

EUROCONTROL.

Appendix H

1.8.6 Aerodrome Operators and Aeronautical Information Service

Providers should establish formal arrangements and assign

responsibilities for maintaining direct and continuous liaison.

Air Navigation Service Provider,

Aeronautical Information Service

Provider,

Aerodrome Operator, Regulator.

Appendix H

31

1.9 TECHNOLOGY

# Recommendation Action Guidance

1.9.1 Improve situational awareness by adopting the use of tech-

nologies that enable operational staff on the manoeuvring

area to confirm their location in relation to the runway e.g.

via GPS with transponder or airport moving maps, visual aids,

signs etc.

Aerodrome Operator,

Air Navigation Service Provider,

Aircraft Operator.

Appendix M

1.9.2 Promote the integration of safety nets to provide immedi-

ate and simultaneous runway and traffic proximity alerts for

pilots, air traffic controllers and manoeuvring area vehicle

drivers.

EUROCONTROL,

SESAR.

Appendix M

32

1.10 CIVIL MILITARY

# Recommendation Action Guidance

1.10.1 Where more than one aerodrome operator exists at a joint-

use aerodrome, a leading aerodrome operator should be

identified to secure a harmonised, consistent and coordinat-

ed application of the recommendations for the prevention of

runway incursions.

Military Aviation

Authority,Regulator.

Appendix I

1.10.2 New investment or reconstruction work on the manoeuvring

area should be planned, coordinated and safety assessed

between civil and military entities, in consultation with the

aerodrome local Runway Safety Team.

Military Aviation Authority,

Regulator, Aerodrome Owner/

Operator,

Air Navigation Service Provider,

aAerodrome local Runway Safety

Team.

Appendix B

Appendix I

1.10.3 Differences in application of Civil and Military traffic proce-

dures that can affect operational safety should be published

in accordance with ICAO Annex 15, Aeronautical Information

Services.

Aerodrome Operator,

Air Navigation Service Provider,

Aeronautical Information Service

Provider,

Military Aviation Authority,

Regulator.

Appendix I

1.10.4 Coordinate civil and military inspection/audit activities and

subsequent safety recommendations with civil and military

authorities.

Regulator,

Military Aviation Authority.

Appendix F

Appendix I

1.10.5 Timely planning and coordination of aerodrome operations

between civil and military aerodrome entities should be

established as appropriate.

Aerodrome Operator. Appendix I

1.10.6 Standard ICAO phraseology should be in use during civil

operations at joint use aerodromes.

Air Navigation Service Provider,

Aircraft Operator.

Appendix A

Appendix E

Appendix I

1.10.7 When practicable, procedures to use VHF frequency for

communications or cross coupled UHF/VHF associated

with runway operations should be developed for civil and

military traffic operating simultaneously. The objective is to

maintain the required level of situational awareness with civil

and military pilots, manoeuvring area vehicle drivers and air

traffic controllers.

Air Navigation Service Provider,

Aerodrome Operator.

Appendix A

Appendix D

Appendix E

Appendix I

1.10.8 On the manoeuvring area, a formation of military aircraft

should be treated as one entity and never split.

Air Navigation Service Provider,

Aircraft Operator.

Appendix I

1.10.9 Conditional clearances should not be used for civilian traffic

during military formation flight operations.

Air Navigation Service Provider. Appendix A

Appendix I

1.10.10

Standard ICAO Annex 14 –Aerodromes, Volume 1 - Aero-

drome Design and Operations aerodrome signs, lights and

markings should be used where civil and military share a

manoeuvring area.

Aerodrome Operator. Appendix A

Appendix I

33

# Recommendation Action Guidance

1.10.11

Wherever practicable, military aircraft should use on-board

lights in accordance with ICAO Annex 2, Rules of the Air.

a.

If required, additional procedures should be applied to main-

tain the required level of situational awareness at joint-use

aerodromes.

Aerodrome Operator. Appendix A

Appendix D

Appendix I

1.10.12

Ensure that military pilots and manoeuvring area vehicle

drivers who are temporarily deployed at civil aerodromes are

competent to operate within the remit of ICAO provisions

and local procedures.

Military Aviation Authority,

Regulator,

Aerodrome Operator,

Aircraft Operator.

Appendix A

Appendix C

Appendix F

Appendix I

1.10.13

EAPPRI recommendations on infrastructure should be

implemented at civil/military joint-use aerodrome at least

where civil aircraft operations are permitted.

Military Aviation Authority,

Regulator,

Aerodrome Operator,

Aircraft Operator.

Appendix J

Appendix K

34

2 FUTURE WORK

# Recommendation Action Guidance

2.1.1 Information about the development of new technologies

that can be applied to runway safety shall be disseminated as

part of the general runway safety awareness campaign.

European regulatory bodies in

coordination with Industry.

Appendix C

2.1.2 Identify any ICAO guidance material that should be upgraded

to ICAO standards and recommended practices and review

other relevant materials.

EUROCONTROL Safety

Improvement Sub Group

(Runway Safety

2.1.3 Monitor and evaluate emerging technologies that may

affect future aerodrome operations. Consider potential

implications concerning runway safety and provide

appropriate guidance:

a.

Remote Tower technologies.

EUROCONTROL Safety

Improvement Sub Group

(Runway Safety).

Appendix M

b.

Authorised Remotely Piloted Aircraft Systems (RPAS)/’drone’

and autonomous vehicle operations on and around the

aerodrome.

2.1.4 Coordinate with other national and regional runway incur-

sion prevention activities.

EUROCONTROL Safety

Improvement Sub Group

(Runway Safety).

Appendix M

35

36

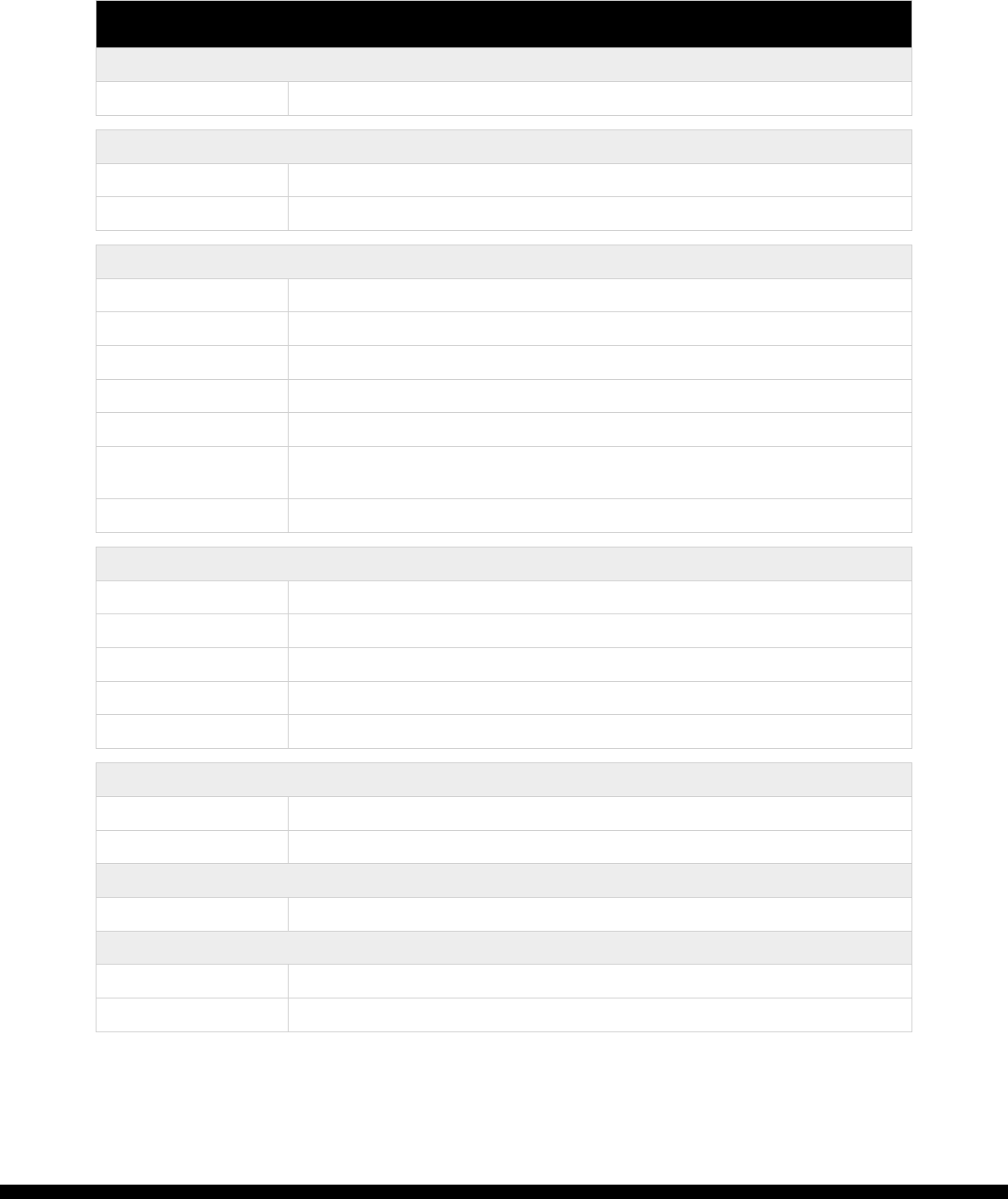

Introduction

Factors affecting communication breakdown

Loss of communication and runway incursions

Aviation language for international services

Runway Frequency

Aerodrome Control Phraseologies

Aerodrome Control Phraseology – READBACK

Avoiding Call Sign Confusion

Communication techniques - general

What to do if uncertain of your position on the manoeuvring area

Conditional Clearance

Improving communications for little or no cost

APPENDIX A

COMMUNICATIONS GUIDANCE

37

38

APPENDIX A COMMUNICATIONS GUIDANCE

INTRODUCTION

The demanding environment associated with aerodrome

operations on a runway requires that all participants

accurately receive, understand, and correctly read back all

air traffic control clearances and instructions. All access

to a runway (even if non-active) should take place only

after a positive ATC clearance has been given / received

and a correct readback has been provided / accepted, and

after the stop bar (where provided) has been switched

off; providing a clearance in a timely manner, as the

aircraft is approaching the relevant runway, will help to

prevent runway incursions. This appendix offers guidance

materials built upon Best Practices from European

aerodromes that may help to protect the integrity of voice

communications for operational staff working on the