For more information or copies of this publication, please contact:

Department of Homeland Security

U.S. Fire Administration

16825 South Seton Avenue

Emmitsburg, Maryland 21727

800-561-3356

www.usfa.dhs.gov

FA-219/June 2008

U. S. Fire Administration

Public Fire Education Planning

A Five Step Process

FA-219/June 2008

Public Fire Education Planning - A Five Step Process

U.S. Fire Administration

Mission Statement

We provide National leadership to foster a solid foundation

for local fire and emergency services for prevention,

preparedness and response.

i

To the Reader:

Public Fire Education Planning: A Five-Step Process describes a systematic approach to designing, im-

plementing, and evaluating community safety education programs.

This manual will help those of you who are new to community safety education understand

some of the basic concepts about how to get started with an organization’s community safety

education programs. It also will assist you with some hints and techniques on a variety of

topics, such as methods for locating partners to assist with community education or tech-

niques for locating resources for your safety programs.

Acknowledgment:

The contributions of the following subject matter experts are gratefully acknowledged:

Management Systems

Training & Technology Co.

1331 Pennsylvania Ave., NW

Suite 1415

Washington, DC

Ed Kirtley, Chief,

City of Guymon Fire Department

Guymon, Oklahoma

Mike Weller

Life Safety Education

Hagerstown Fire Department

Hagerstown, Maryland

USFA Project Team

John Cochran,

Fire Management Specialist

Kathleen Gerstner,

Public Fire Education Specialist

Gerry Bassett,

Training Specialist

Table of Contents

Public Fire Education Planning:

A Five-Step Process

Introduction

Chapter 1

Step 1: Conduct a Community Risk Analysis ............................................................................................ 1-1

Identify Data to be Analyzed ....................................................................................................................... 1-3

Develop a Community Risk Profile ............................................................................................................ 1-14

Write a Problem Statement ....................................................................................................................... 1-16

Prioritize Issues ......................................................................................................................................... 1-17

Identify Target Areas and Populations ........................................................................................................ 1-19

Chapter 2

Step 2: Develop Community Partnerships ................................................................................................ 2-1

Identify Possible Partners ............................................................................................................................ 2-2

Interpret Community Risks and Problems................................................................................................... 2-3

Form a Community Planning Team ............................................................................................................. 2-4

Chapter 3

Step 3: Create an Intervention Strategy .................................................................................................... 3-1

Review Data about Risks and Target Populations ......................................................................................... 3-3

Identify Places for Intervention ................................................................................................................... 3-3

Identify Target Populations and Locations ................................................................................................... 3-4

Identify Interventions ................................................................................................................................. 3-7

Identify Resources Required ..................................................................................................................... 3-10

Develop the Evaluation Strategy ................................................................................................................ 3-12

Chapter 4

Step 4: Implement the Strategy ................................................................................................................. 4-1

Conduct Pilot of Intervention ..................................................................................................................... 4-3

Establish Responsibilities and Timetable ...................................................................................................... 4-4

Market Intervention Programs .................................................................................................................... 4-6

Initiate Activities.......................................................................................................................................... 4-8

Monitor Progress......................................................................................................................................... 4-8

Report Progress Periodically ........................................................................................................................ 4-9

Chapter 5

Step 5: Evaluate the Results ....................................................................................................................... 5-1

Collect Data ................................................................................................................................................. 5-2

Compare Data to Baseline............................................................................................................................ 5-3

Note Interventions as Necessary.................................................................................................................. 5-5

Modify Interventions as Necessary .............................................................................................................. 5-6

Report Results to Sponsoring Organization and Community ...................................................................... 5-7

Conclusion

Bibliography

Appendix

ii

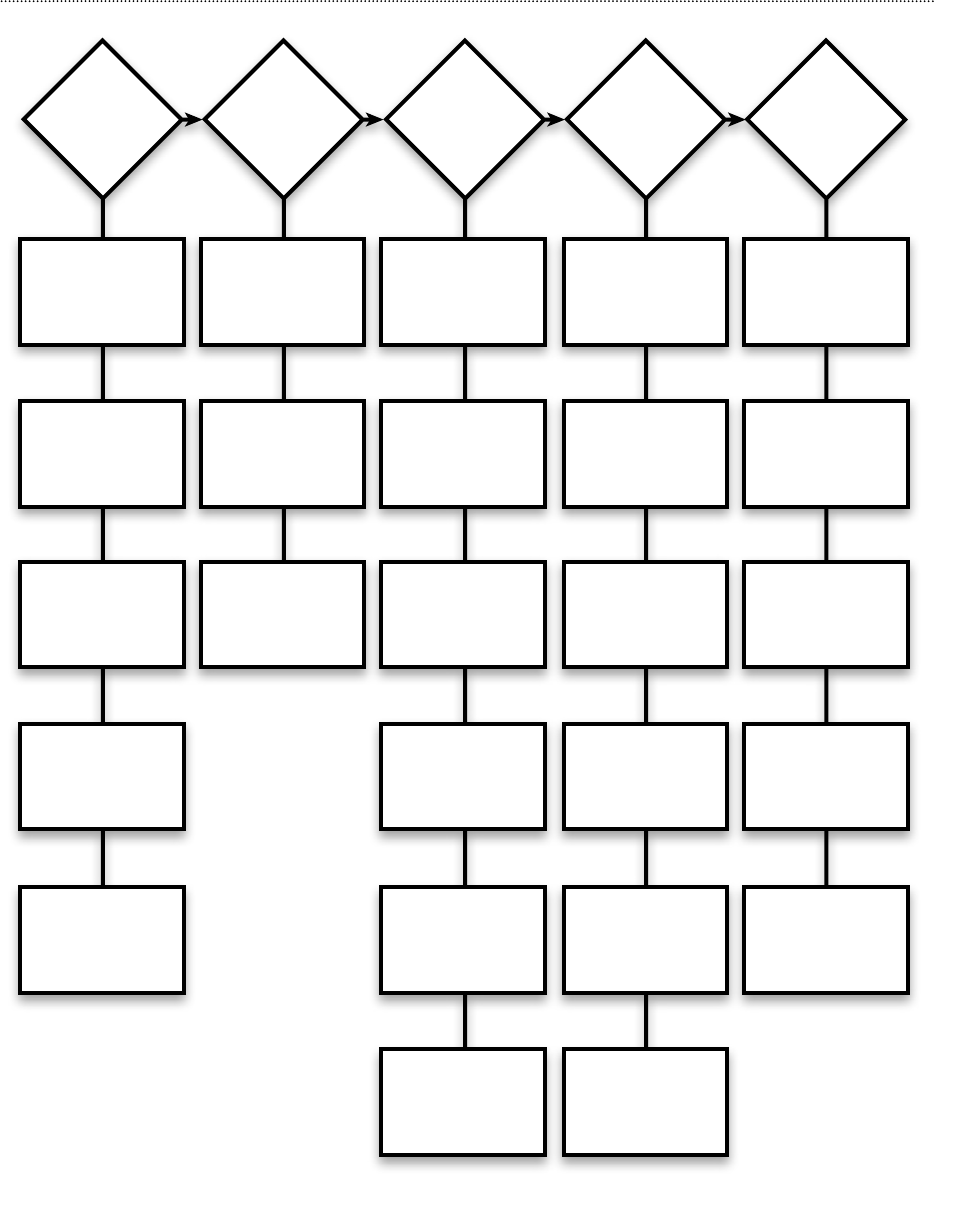

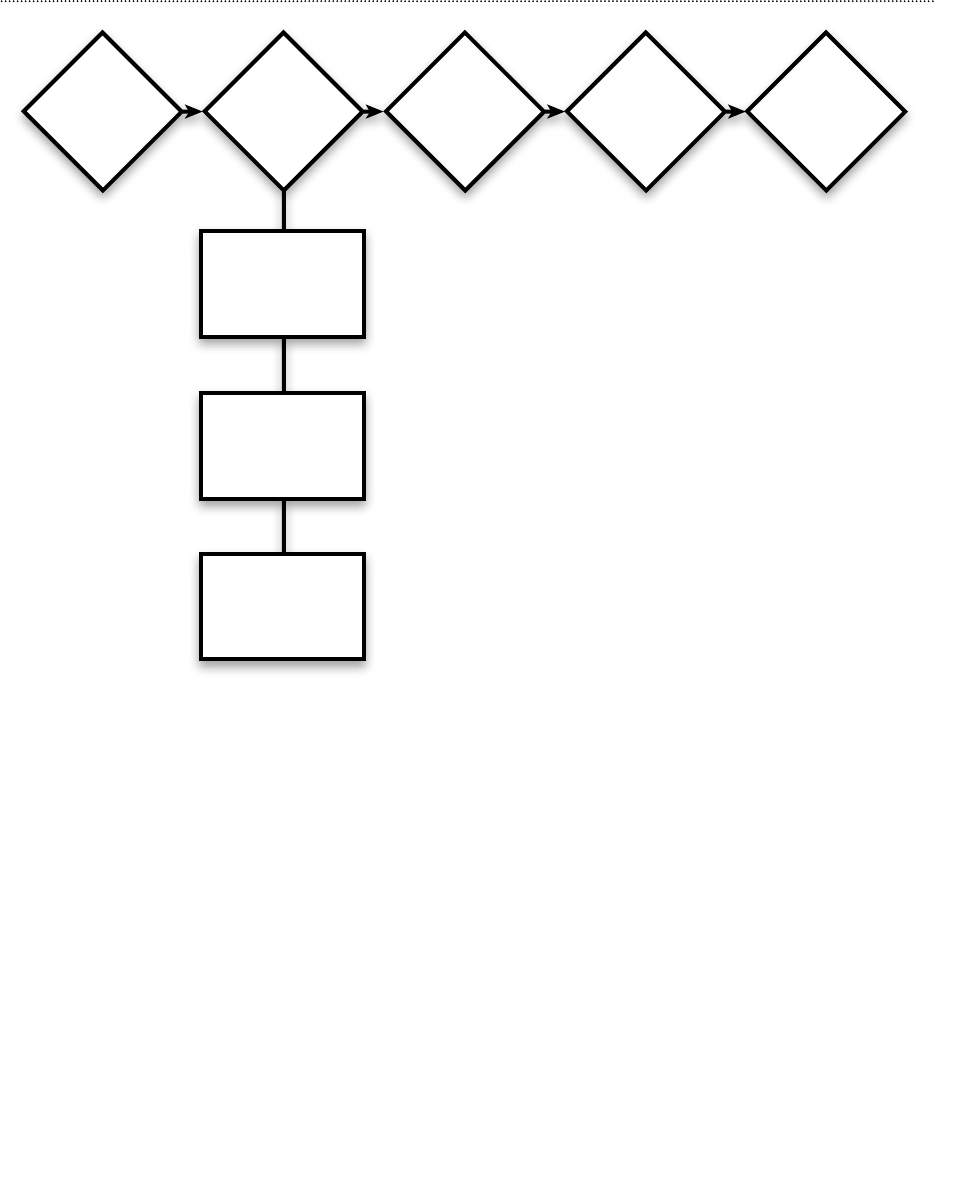

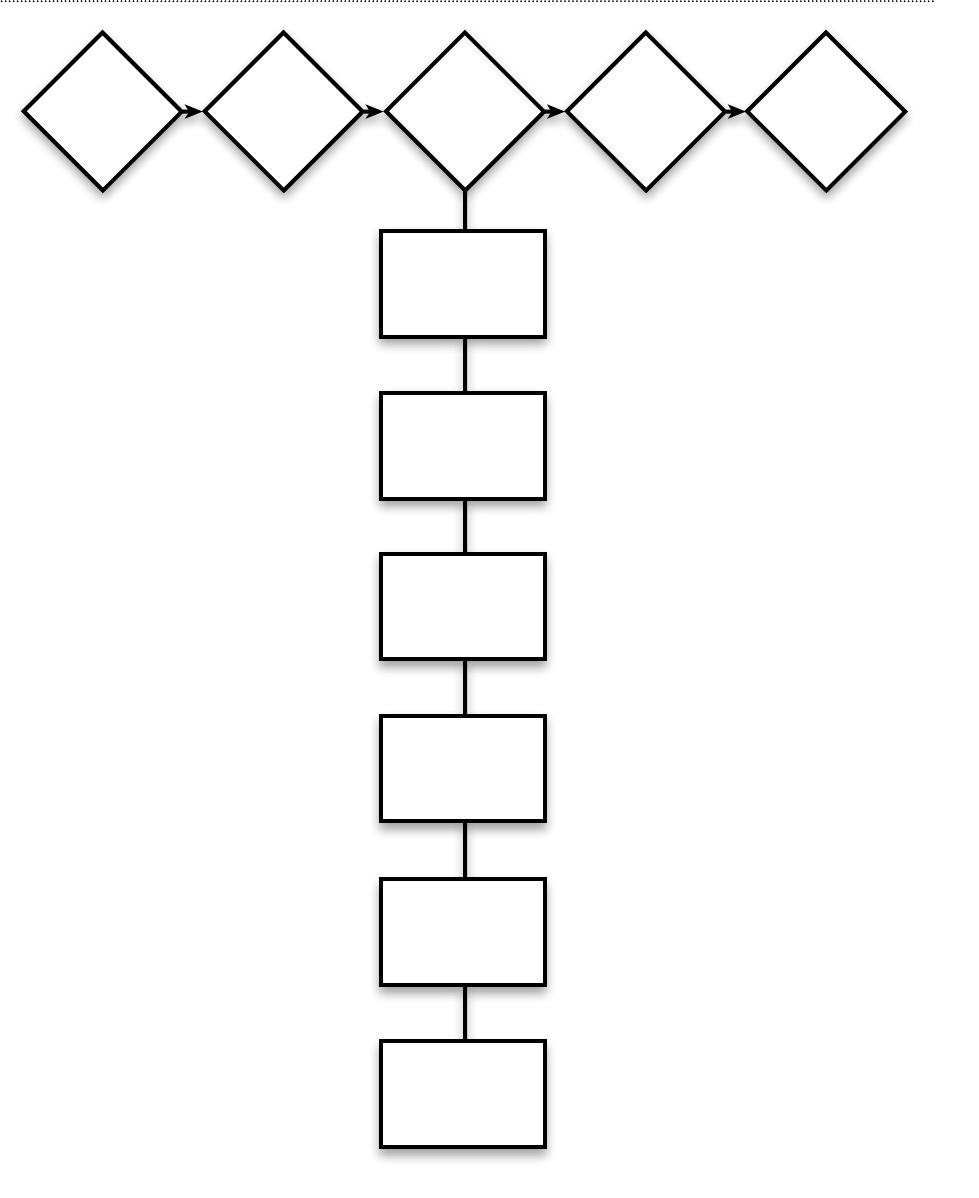

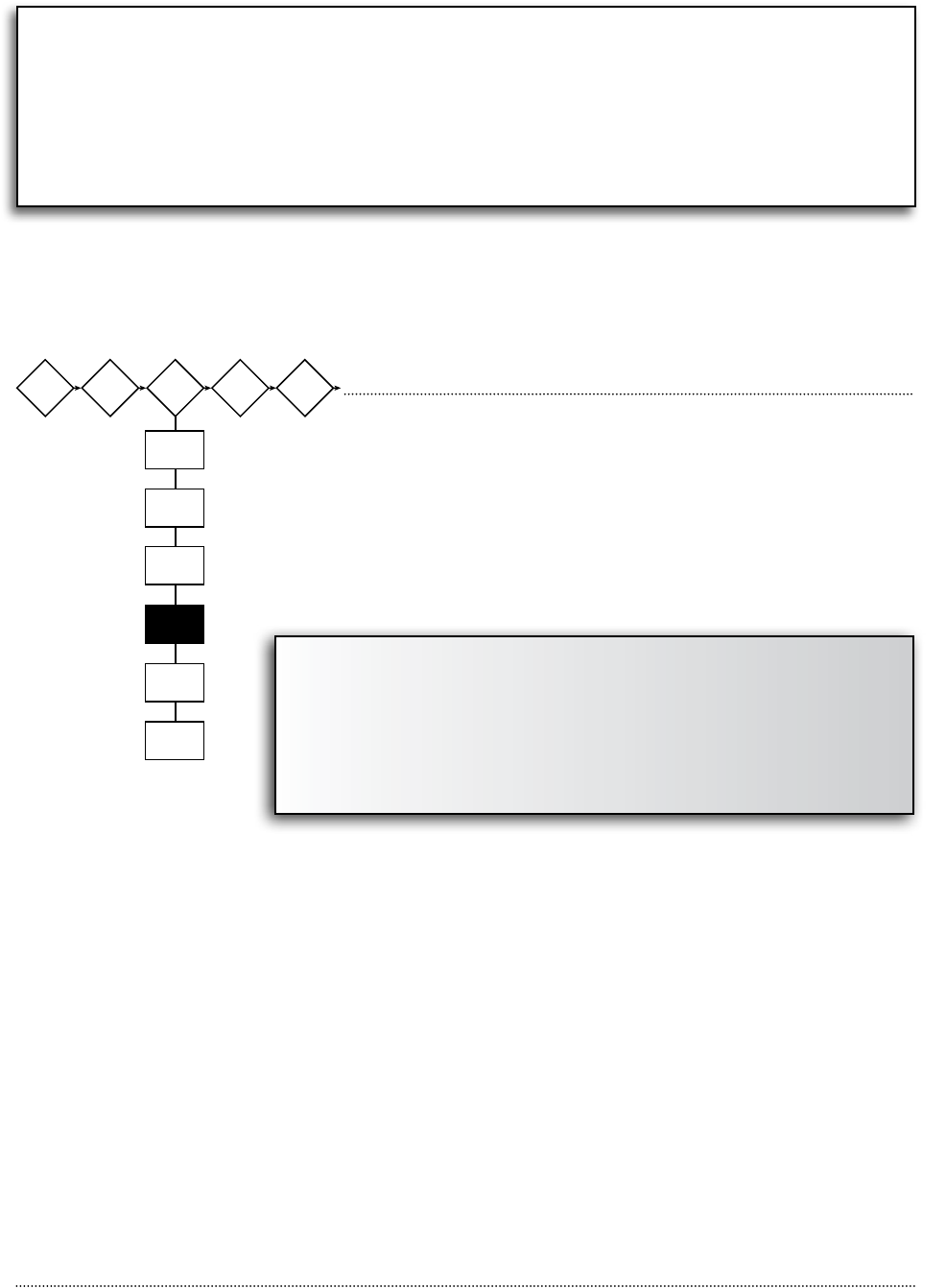

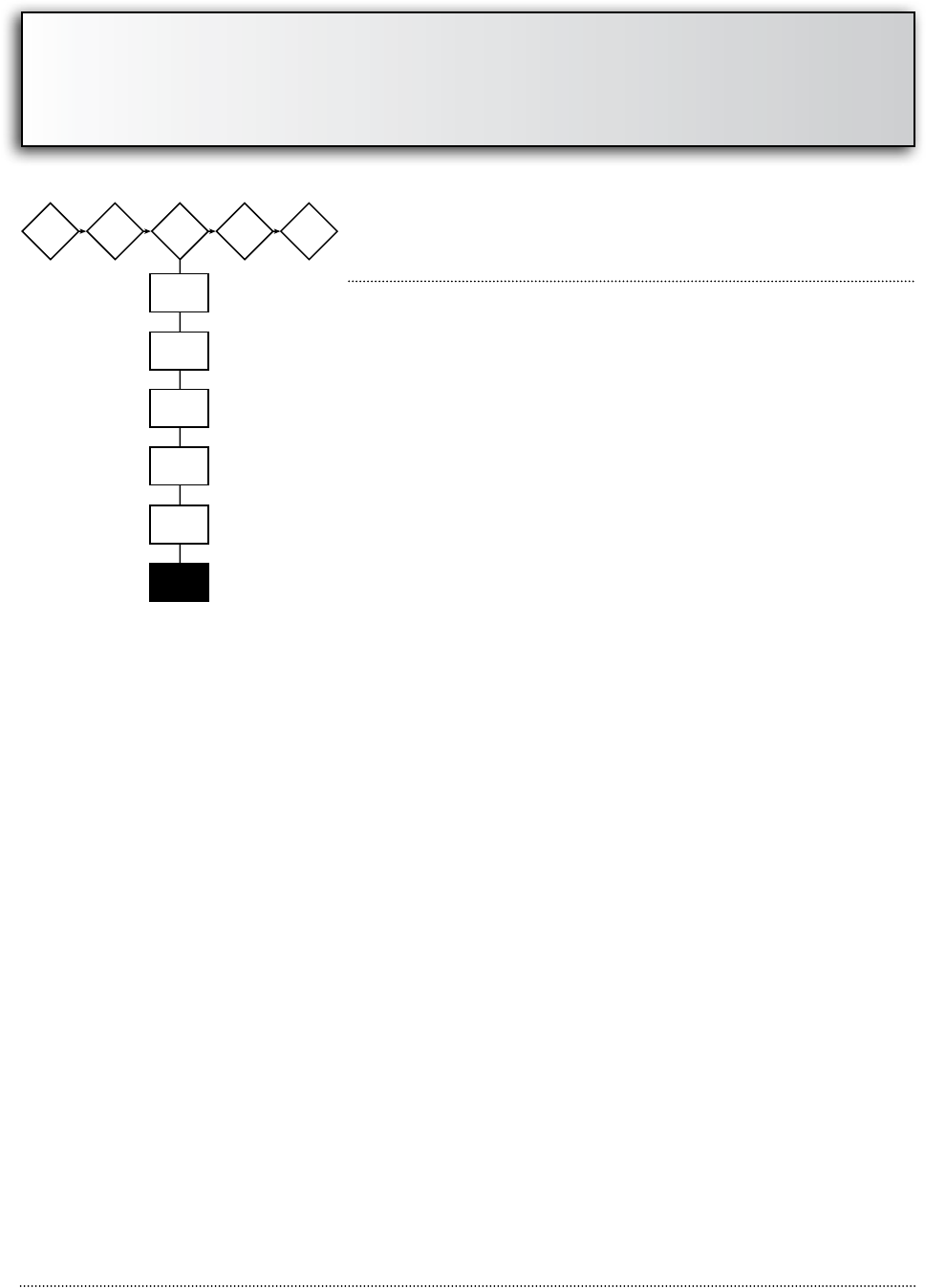

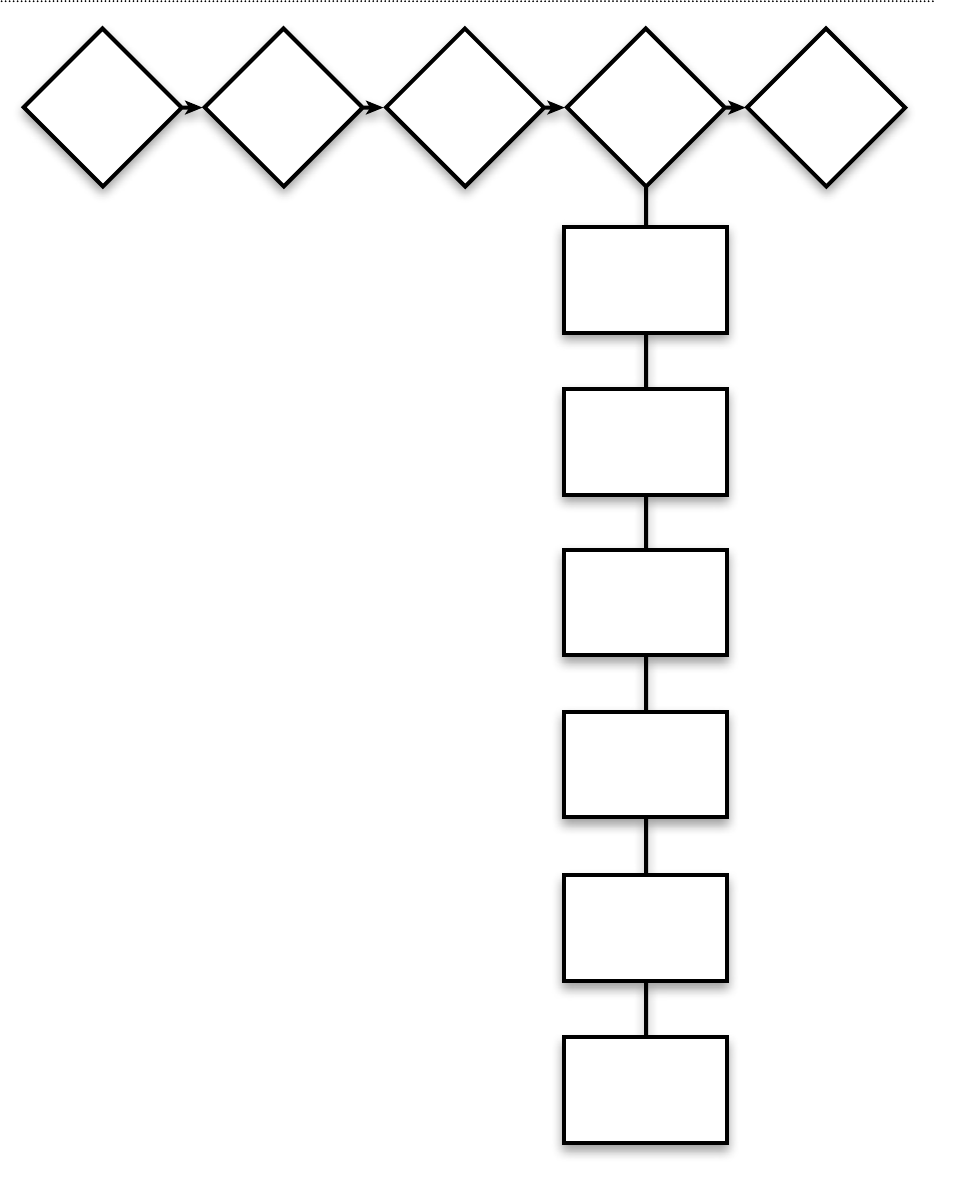

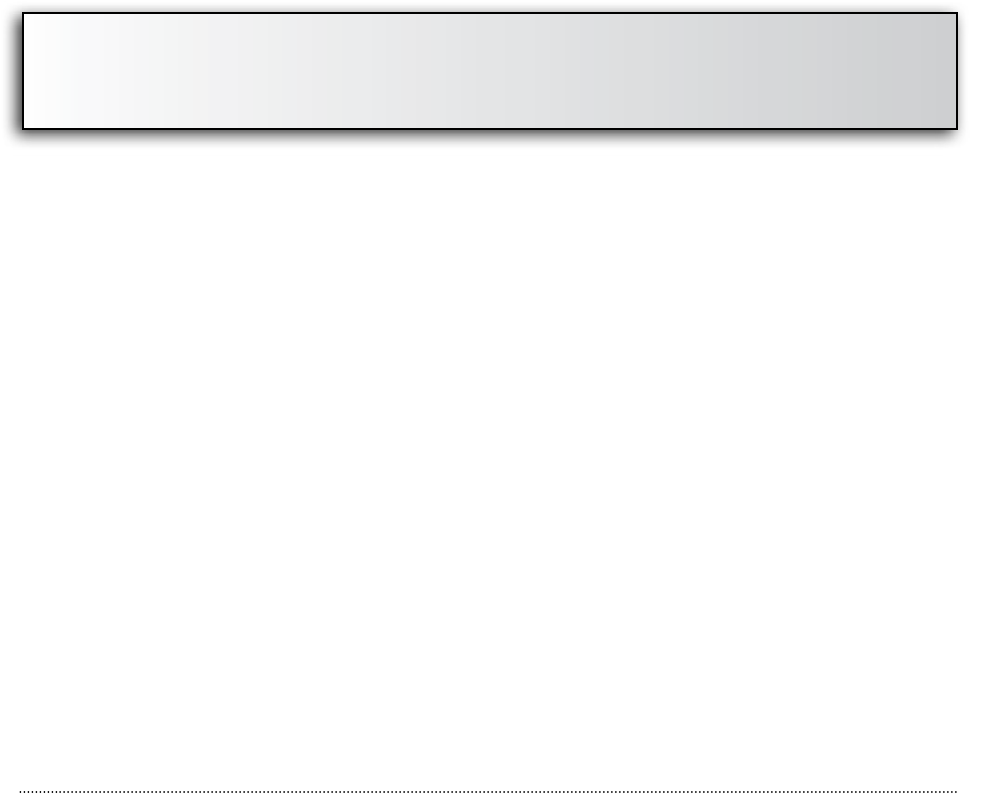

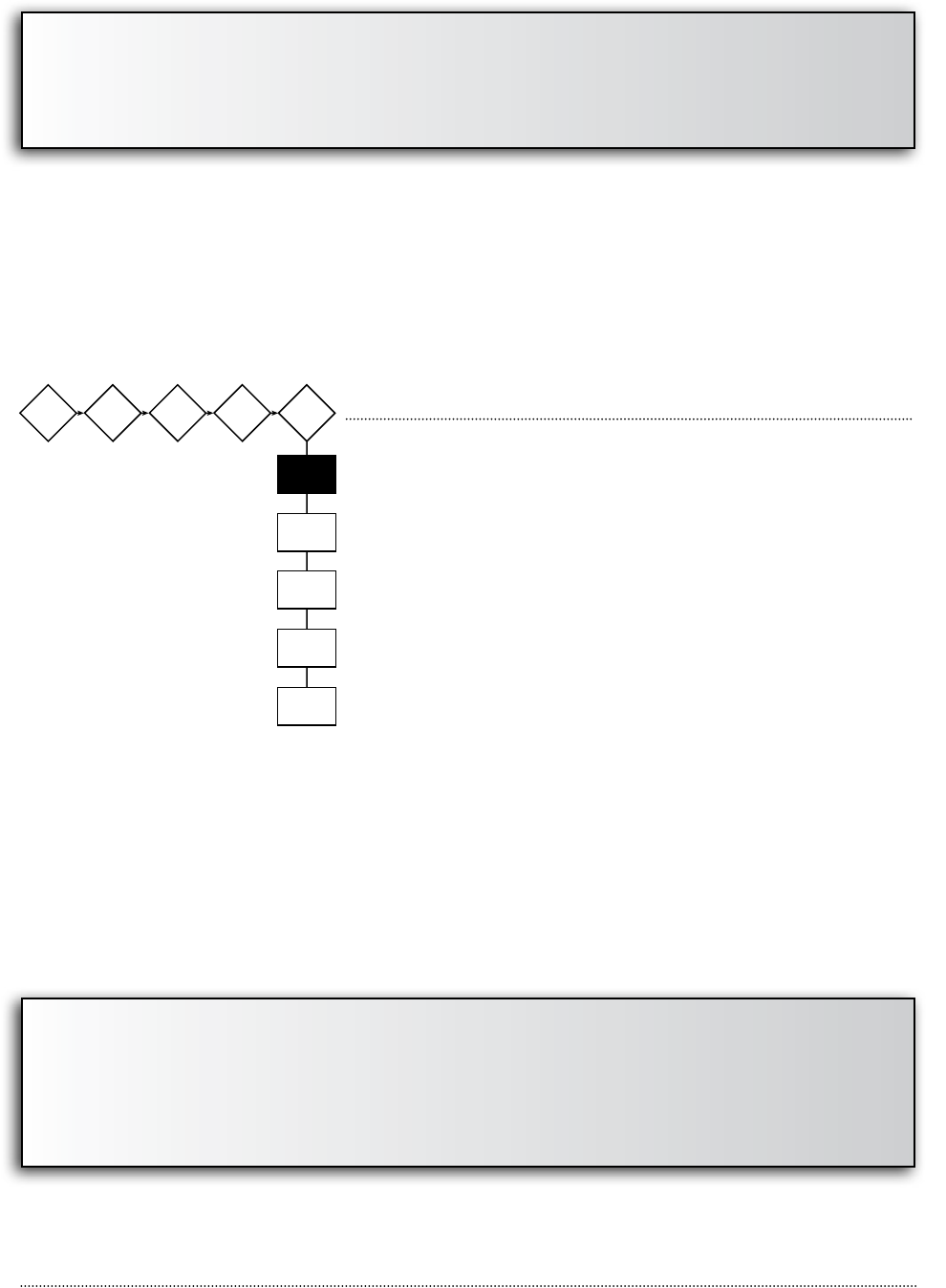

Five-Step Process Summary

Step 1: Conduct a Community Risk Analysis

A community risk analysis is a process that identifies fire and life safety problems and the

demographic characteristics of those at risk in a community.

Step 2: Develop Community Partnerships

A community partner is a person, group, or organization willing to join forces and address

a community risk. The most effective risk reduction efforts are those that involve the com-

munity in the planning and solution process.

Step 3: Create an Intervention Strategy

An intervention strategy is the beginning of the detailed work necessary for the development

of a successful fire or life safety risk reduction process. The most successful risk reduction ef-

forts involve combined prevention interventions:

Education: Providing information (facts) about risk and prevention.

Engineering: Using technology to create safer products or modifying the environ-

ment where the risk is occurring.

Enforcement: Rules that require the use of a safety initiative.

Step 4: Implement the Strategy

Implementing the strategy involves testing the interventions and then putting the plan into

action in the community. It is essential that the implementation is well-coordinated and se-

quenced appropriately. Implementation occurs when the intervention strategy is put in place

and the implementation plan schedules are followed.

Step 5: Evaluate the Results

The primary goal of the evaluation process is to demonstrate that the risk reduction efforts

are reaching target populations, have the planned impact, and are demonstrably reducing

loss. The evaluation plan measures performance on several levels, outcome, impact, and pro-

cess objectives.

iii

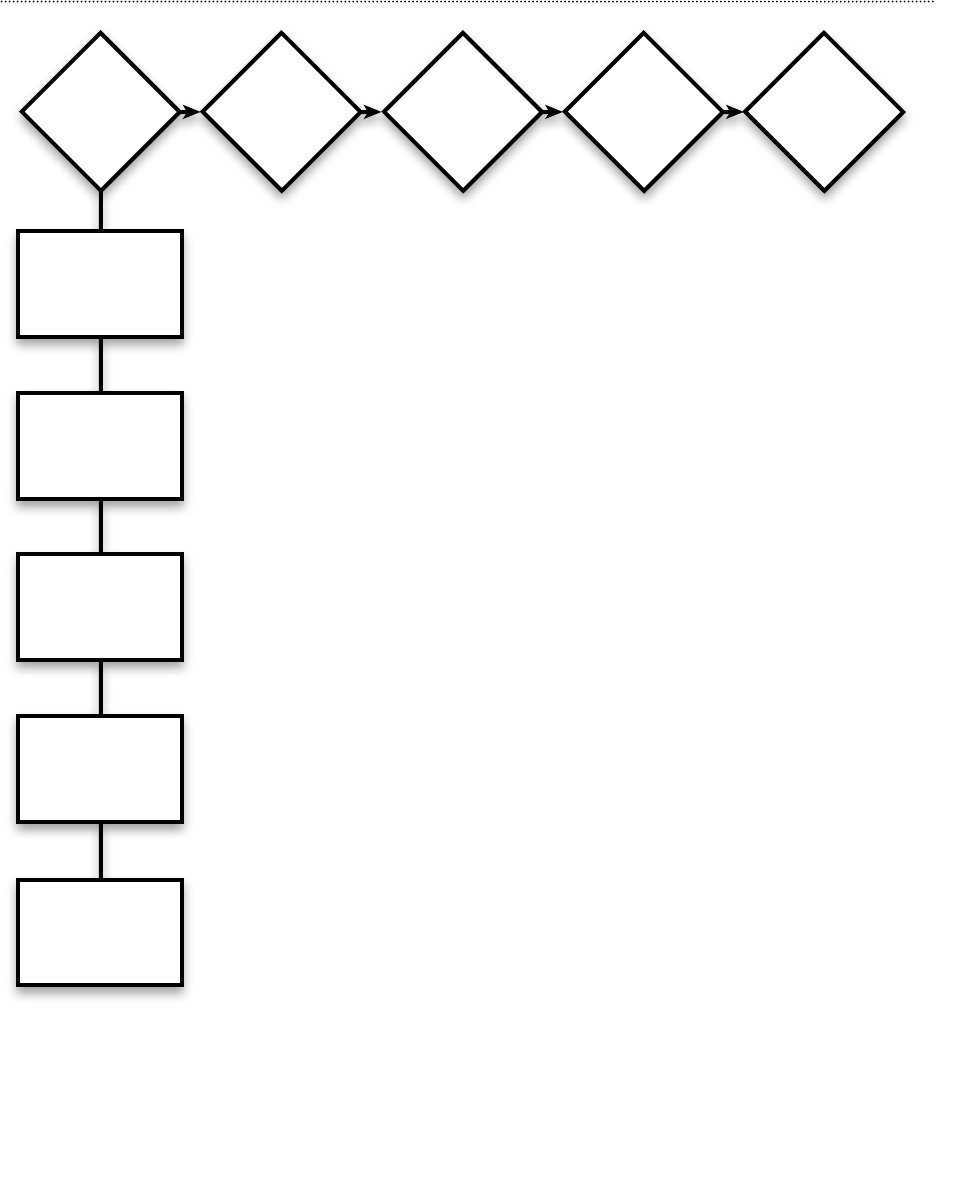

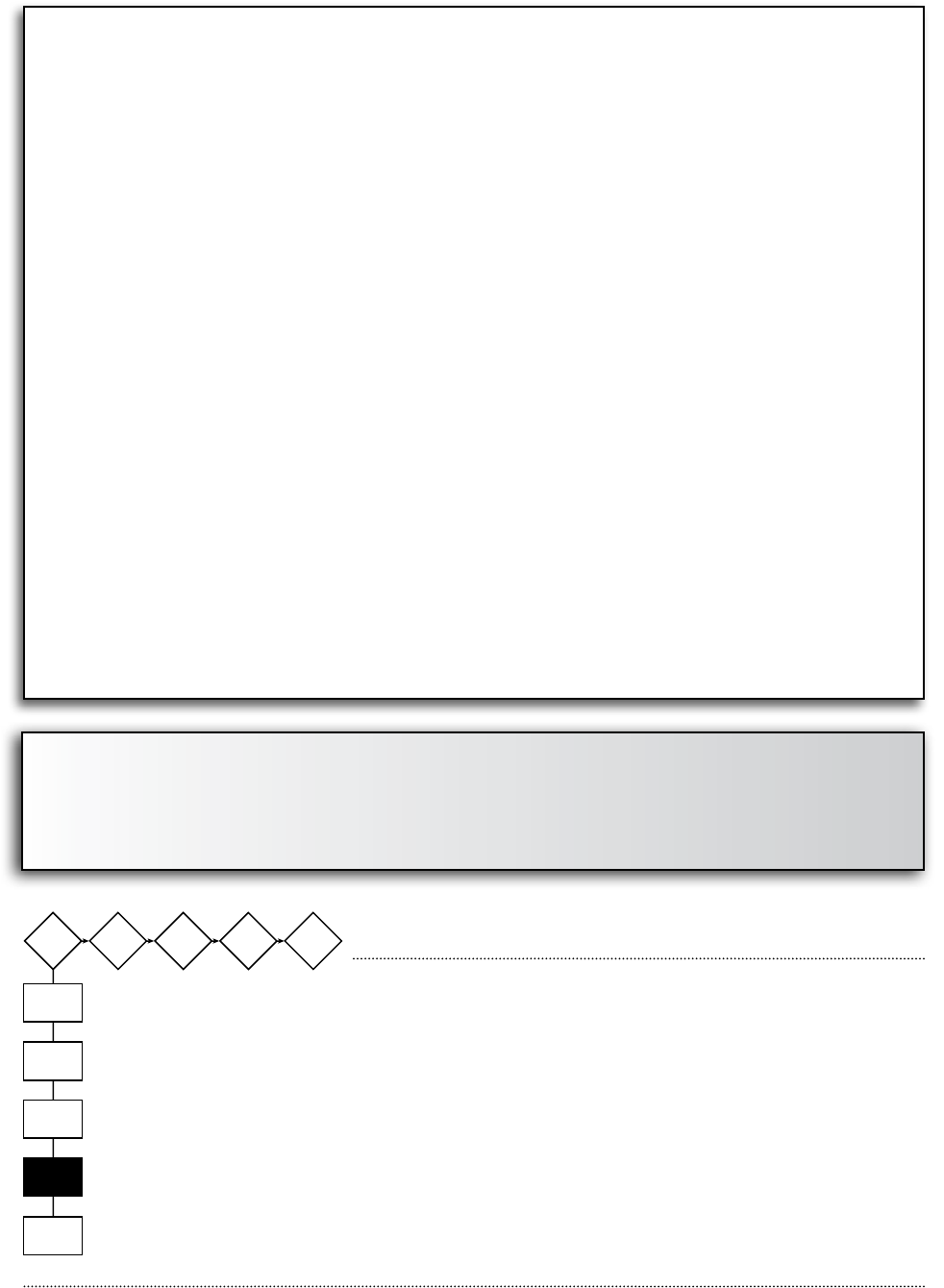

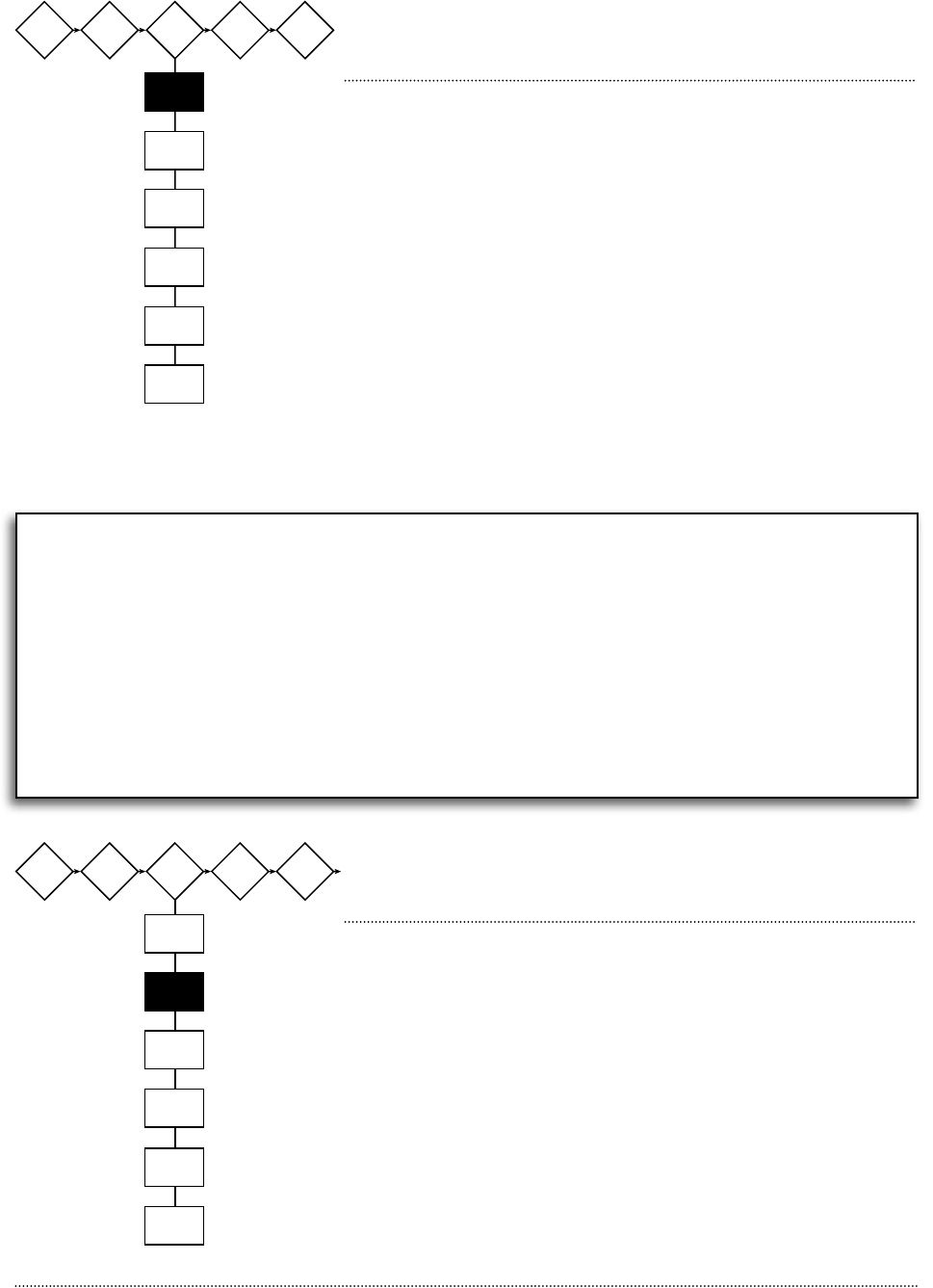

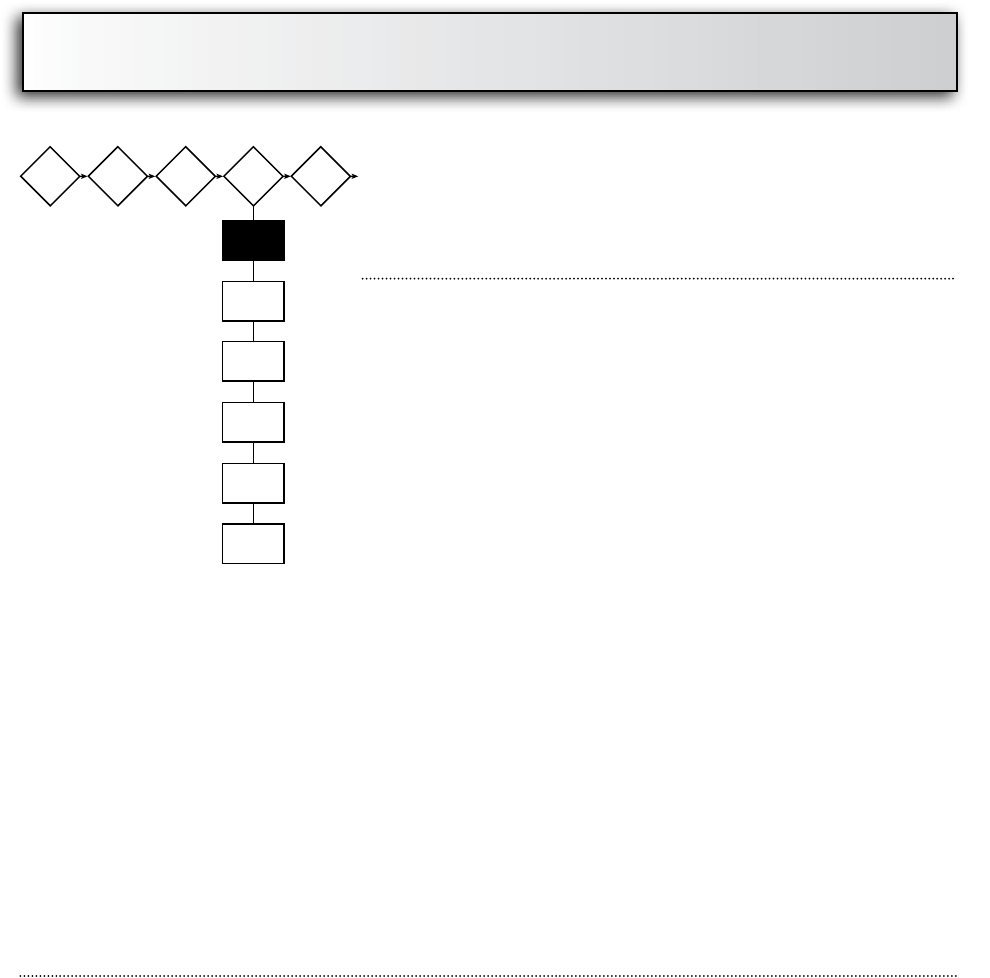

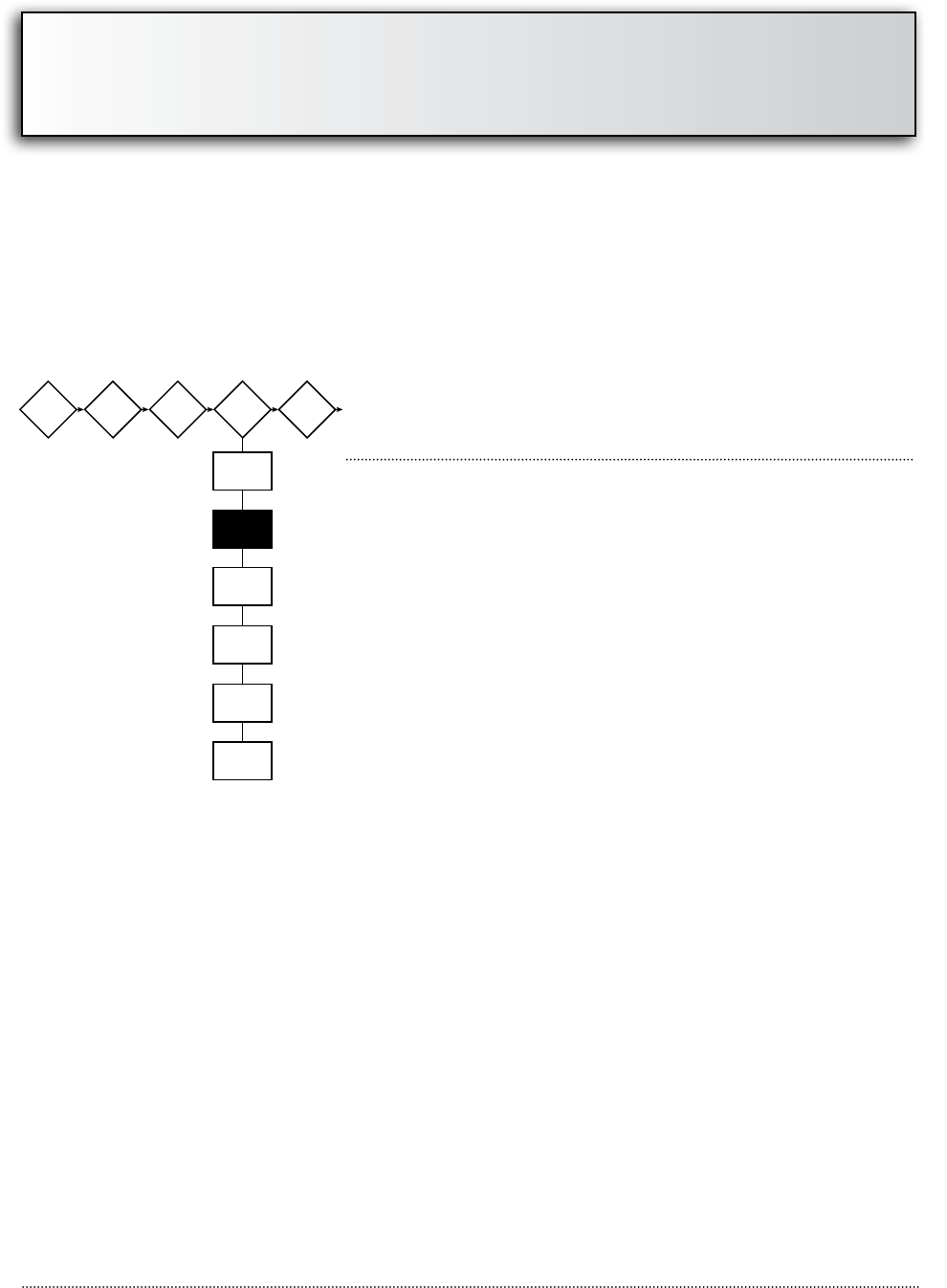

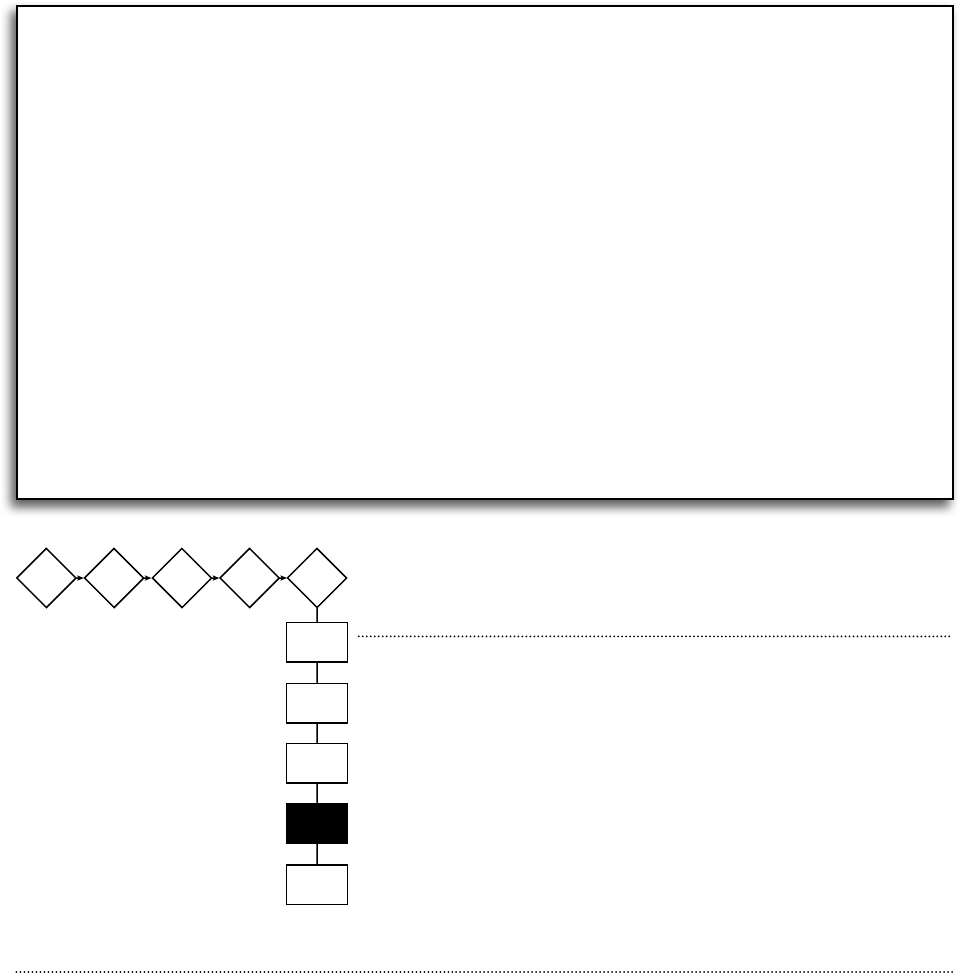

Conduct a

Community

Risk

Analysis

Develop

Community

Partnerships

Create an

Intervention

Strategy

Implement

the

Strategy

Evaluate

the

Results

Identify Data

to be

Analyzed

Identify

Possible

Partners

Review Data

about Risks and

Ta rget Populations

Conduct Pilot of

Intervention; Revise

as Necessary

Collect

Data

Develop a

Community Risk

Profile

Interpret

Community Risks

and Problems

Identify Places

for

Intervention

Establish

Responsibilities

and Timetable of

Activities

Compare Data

to

Baseline

Write a

Problem

Statement

Form a

Community

Planning Team

Identify Ta rget

Populations

and Locations

Market

Intervention

Programs

Note

Interventions

as Necessary

Prioritize

Issues

Identify

Interventions

Initiate

Activities

Modify

Interventions as

Necessary

Identify Ta rget

Areas and

Populations

Identify

Resources

Required

Monitor

Progress

Report Results

to Sponsoring

Organization and

Community

Develop the

Evaluation

Strategy

Report

Progress

Periodically

Introduction

Introduction

Introduction - 1

The purpose of this guide

Today fire departments use many terms for educational fire and injury prevention programs.

Programs differ in size and approach, but the goals are the same: Change the behavior of the

public so that there are fewer dangerous situations, fires, and injuries.

This guide uses a five-step planning process for developing and implementing successful fire

and life safety public education programs. From identifying the fire and injury risks in the

community, developing and implementing a program, and evaluating the results, planning

is the process that ensures that the program strategies and initiatives really address the prob-

lems. This guide takes you step by step through that planning process.

A successful program follows a ve-step process:

1. Conduct a community analysis.

2. Develop community partnerships.

3. Create an intervention strategy.

4. Implement the strategy.

5. Evaluate the results.

The temptation to “just get something implemented” is hard to resist. Unfortunately, this is a

trap. Yes, it’s easy to schedule some presentations at a school; pass out brochures, stickers, and

plastic helmets; and do some media interviews. But do those presentations address the com-

munity’s worst fire or injury problems? Do the solutions being promoted really work? Is the

appropriate target audience even being reached? Are community groups working together?

Is the program being implemented in the best way?

A “ready, fire, aim” approach will not hit the target. It can give the impression that the depart-

ment is out there educating the public, but may achieve little else. Successfully reducing fires

and preventable injuries involves effective community planning. Notable public education

programs around the country always prove this to be true.

This updated guide recognizes that fire prevention is now an important part of the larger

goal of preventing injuries and unsafe situations. Fire departments often provide emergency

medical services. Preventing injury, illness, and other unsafe situations is often part of the

mission of saving lives.

What is the history of public education?

America Burning

Public education as an important component of a fire department’s mission came to the fore-

front when America Burning was published in 1973. This report of the National Commission on

Fire Prevention and Control, the forerunner of the United States Fire Administration (USFA),

provided both insight into the scope of the American fire problem and possible solutions.

America Burning identified the need for public education as part of an overall prevention strat-

egy. “Public education about fire has been cited by many Commission witnesses and others

as the single activity with the greatest potential for reducing losses.”

1

Motivational Psychology Fire Prevention Study

In 1974, Richard Strother published a report called “A Study of Motivational Psychology

Related to Fire Prevention Behavior in Children and Adults,” one of the first scientific studies

to document the effectiveness of public education messages. It also demonstrated the impor-

tance of evaluation as an essential part of a public education program.

Public Fire Education Planning: A Five-Step Process

In 1977, the National Fire Prevention and Control Administration published a program for

public educators detailing an effective planning model. Public Fire Education Planning: A Five-Step

Process is a model that’s been used for years by public educators to develop and implement

fire safety education programs. The basic approach is still applicable today; however, changes

in culture and the scope of problems require the updated planning model provided in this

guide.

Learn Not to Burn

In 1979, the National Fire Protection Association (NFPA) introduced a new fire safety cur-

riculum for use in elementary schools; Learn Not to Burn

©

was the first nationally available

school-based curriculum to address fire safety behaviors for young children. The curriculum

is based on research into the fire problem, the needs and characteristics of the target audi-

ence, and the behaviors appropriate for the target audience. In other words, Learn Not to Burn

©

is the culmination of a public education planning process.

Reaching the Hard to Reach

In 1981, the TriData Corporation, in cooperation with the USFA, published Reaching the Hard

to Reach. This document emphasizes the need for local-level planning to identify the best ap-

proaches for reaching difficult-to-reach target audiences.

Introduction - 2

1

National Commission on Fire Prevention and Control, America Burning: The Report of the National Commission on Fire

Prevention and Control (Washington: U.S. Fire Administration, 1973) 105.

Introduction - 3

National Safe Kids Campaign

A new public education era began in 1988 when SAFE KIDS Worldwide was initiated in Wash-

ington, DC. The campaign is a cooperative effort between the National Children’s Hospital

and Johnson & Johnson Corporation. The goal is to reduce preventable childhood injuries,

including those from fire. Safe Kids focuses on two key messages. First, public education initia-

tives must be based on local problems and target the people at risk. Each community must

conduct its own planning process to identify specific problems and the best methods for

addressing them. Secondly, any local initiative must involve the entire community. One orga-

nization alone can’t make a big impact in preventing fires and injuries. Fire departments are

recognizing that preventable injuries are as much of a problem in their communities as fires.

Today, many fire departments have accepted the concept of working with other organizations,

and have become key members of local Safe Kids coalitions.

Risk Watch

In 1995, the NFPA began working with the National Safe Kids Campaign to develop an all-risk

injury prevention curriculum called Risk Watch

®

. Again, effective planning proved to be a key

to the project’s success. Using the planning process, the NFPA was able to identify the major

risk areas for children, determine appropriate messages and behaviors, and develop success-

ful methods for teaching the behaviors and messages. Risk Watch

®

is now an effective public

education tool.

Lessons Learned

Since 1973, there have been many lessons learned about what constitutes effective public

education initiatives at the local level. Experience shows that successful programs have the

following characteristics:

• There is strong individual and organizational commitment to the public education

initiatives. The initiatives involve more than a few presentations and distribution of bro-

chures. Successful public educators understand the amount of effort involved and commit

themselves to a long-term approach. In addition, the organization’s leaders understand

that the program requires full organizational commitment that includes time for person-

nel to work on the program, resources required to buy materials and equipment, and

most importantly, visible program support from all department members and other local

decisionmakers.

• The program is based on a comprehensive planning process that identies commu-

nity re and injury problems, and the people most likely to be involved. Few, if any,

successful programs are haphazard. Organizations with successful programs have used a

planning process. In some cases this takes time. In other cases (for example, in a small

community with a specific problem) the process may be shorter. The complete planning

process should be used by organizations of all sizes.

Introduction - 4

• Partnerships are established so that the community as a whole is involved in the so-

lutions. Solutions to fire and injury problems can be complex. Several local organiza-

tions should form a team and work together to solve community safety problems. This

approach brings a variety of resources to bear on the problem and reduces the cost to

any one organization. Everyone has a vested interest in the success of the program and in

improving the quality of life of the target audience.

• There is an evaluation of the program’s results and processes. Evaluation is crucial to

determining if a program’s goals have been achieved, and essential to planning future

programs. Evaluation identifies what worked, what didn’t work, and what to do in the

future to be successful. The evaluation also provides the ammunition needed to market

the program to the community.

What has improved?

Public education, along with engineering and enforcement (the three E’s), have reduced fires

and related deaths, burn injuries, and other types of preventable injuries. Consider the fol-

lowing fire and injury statistics:

• From1995to2004,overallreincidentsdeclinedsteadilyby20percent.

• Thenumberofannualdeathsduetoredeclined21percentfrom1995to2004.Now

the annual average is fewer than 4,000 deaths each year.

• From1995to2004,thenumberofinjuriesfromresidentialresdecreasedby29per-

cent.

• Thedeathratefromreamongchildren14andunderdeclinedby68percentfrom1987

to 2005.

• Theoverall unintentional injury-relateddeathrateamongchildren14 and under de-

creased by 45 percent between 1987 and 2005.

However, additional statistics indicate that more work is needed. Consider some different

statistics:

• Thegreatestnumbersofredeathsoccurinthehome,withthemajorityinone-and

two-family dwellings.

• In2005, morethan1,400childoccupants(0-14)died inmotorvehiclecrashesand

nearly half were unrestrained. In the same year, 203,000 child occupants were injured.

• Everyyearmorethan5,000Americanchildrenages14andunderdiefromunintentional

injury

Introduction - 5

• Theelderly,theyoung,andthepoorcontinuetobeatasignicantlyhigherlevelofrisk

from fire than the average person.

• WhileAfrican-Americansaccountfor13percentofthepopulation,theyaccountfor24

percent of the annual fire deaths.

• Theamountofannualpropertylossduetoreeachyearaverages$11billion.

What needs to be done in the future?

The 2000 USFA report, America Burning Recommissioned, states, "There is wide acknowledgement

and acceptance that public education programs on fire prevention are effective...no preven-

tion effort can succeed without a public education component."

2

Fire service leaders and public educators responsible for programs must use new educational

approaches, methods, and processes, such as the following:

• Greater organizational focus on prevention. Fire departments must continue to increase

the emphasis on prevention initiatives. Prevention is an important, cost-effective risk re-

duction tool. Fire chiefs, fire marshals, public educators, and all fire service leaders must

be advocates for these initiatives. They should be the national leaders in fire and injury

prevention efforts.

• Improved data collection and analysis. This directly supports the need for better plan-

ning. Currently, information on fires is available in most States through the National Fire

Incident Reporting System (NFIRS). However, there are voids in available information.

It is essential that each community gather data on fires and preventable injuries. This re-

quires collaboration with agencies such as law enforcement, hospitals, burn units, health

departments, and State fire marshals. Data analysis is part of the overall planning process,

as well as the development of an effective public education program.

• Integrated use of prevention interventions. The most effective prevention programs

incorporate education, code enforcement, and engineering interventions in one com-

prehensive prevention strategy. The three interventions working together hit the problem

from all sides so the ability to reduce deaths and injuries is improved dramatically.

• Improved technology. Safety technology is progressing rapidly. No longer are the smoke

alarm and automatic sprinkler system the only prevention tools available to the public

educator. New technologies include digital projectors, fire detection systems that provide

building occupants with more time to escape from a fire, and computers that increase the

ability of the public educator to reach others with prevention messages. These technolo-

gies must be part of the public educator's toolbox and be integrated into education and

prevention programs.

2

U.S. Fire Administration, America Burning Recommissioned (Washington: Author, 2000) 24.

Introduction - 6

• Higher level of prevention and public education training for emergency services per-

sonnel. Firefighters and emergency medical technicians (EMTs) are routinely delivering

public education presentations and assisting with public education activities. They must

be adequately trained in educational methods. NFPA 1001, Standard for Fire Fighter Profes-

sional Qualification requires new firefighters to have the skills to deliver a public education

presentation from a prepared lesson plan. NFPA 1021, Standard for Fire Officers, specifies

the requirement of the ability to deliver presentations and also to develop a department

public education program. These skills can be included in job descriptions and specified

as a prerequisite for promotion. Every emergency service provider is a public educator at

some level, and can benefit from public education training.

• Changing the current paradigms about the causes of re and injuries. The term “ac-

cident” has been used for years to describe the cause of fires and injuries. By definition,

an accident is an uncontrolled event—something that cannot be predicted or prevented.

When matches are left in the reach of a young child and that child starts a fire with

them, it is not an accident. It is an incident that could have been prevented. When a fire

occurs in a home without a working smoke alarm and the residents are killed, it is not

an accident. A working smoke alarm and education on home escape plans can prevent

these deaths. The public educator must teach the public that injuries and fires are seldom

accidents. Rather, they are predictable events that can be prevented through education,

enforcement, and engineering initiatives.

Can I make a difference?

This is a question that many newly-appointed public educators ask. The answer is, without a

doubt, yes! Public education has proved itself over and over as an effective prevention strate-

gy. The SAFE KIDS Worldwidecampaignestimatesthat,onaverage,a$33smokealarmgenerates

$940inbenetstosociety,suchasmedicalcostsandothercostsassociatedwithresuppres-

sion and property loss. What a return on an investment of one dollar! Safe Kids also estimates

that as many as 90 percent of unintentional injuries to children can be prevented.

Community risk reduction uses prevention processes to reduce or eliminate hazards and risks

in the community, thus reducing the frequency and severity of fires and injuries. This effort

requires planning. But the foundation for success is laid long before the planning step. First,

it’s important to have proactive individual and organizational attitudes about the community

education program, and a strong personal and organizational commitment to making the

program achieve its goals and objectives.

The community educator is the heart and the soul of the program. This person must motivate

others to be involved and support the program. A sound, rational argument for your commu-

nity education program is important. However, a positive attitude and strong commitment is

what actually convinces others that a program should be implemented.

Introduction - 7

Department and community members will assess the level of commitment on the part of the

department leadership. Does the fire chief support community education? Is the fire chief

providing money, time, and people for the program? Do the fire chief and other senior of-

ficers make community education part of day-to-day operations? When others see that com-

munity education is part of the department’s mission, they will lend their support. Commu-

nity involvement is needed to be successful.

What is my personal commitment?

Several specific actions are needed to build and maintain an effective planning process and a

successful community education program. These actions become a personal action plan.

Do the right things and do things right. It is important to have an understanding of the steps

that must be completed in order to establish a sound program. This includes completing a

planning process, gaining support of the department leaders, and developing a partnership

with the community. Take the time to do quality work. Short cuts seldom work and often

take more time to fix than doing it right from the start. Be dependable and willing to do your

share.

Invest the required time and effort. Organizing successful community education initiatives

takes time, resources, and support. It takes time to build a community partnership and to

develop a relationship with the target audience.

Follow a proven successful process to identify and reduce community risk. This guide

provides a proven method for conducting a planning process. However, take the time to read

journal articles and textbooks on community education. If possible, attend the National Fire

Academy (NFA) community education courses, or similar courses taught at the State or local

level. It helps to learn several proven methods of planning community education and risk

reduction. Get insight into programs that have been less than successful and avoid falling into

the same traps.

Collect data and be objective. No one knows all the answers to solving fire and injury prob-

lems. Be objective in your decisionmaking and in the use of educational methods. Before

guessing about the community’s problems and risks collect accurate data. Don’t rely on intu-

ition to determine solutions. Instead, meet with the target audience and the other members

of the community team. Get as much information as you can from them and then analyze

what the information means. If needed, get help in the analysis but don’t get stuck in ‘‘pa-

ralysis from analysis.’’ Step forward, make decisions, and move ahead.

It is easy to become protective of department initiatives and programs, even to the point

of excluding other agencies. Be willing to give up sole program ownership and encour-

age others to share ownership

Introduction - 8

Be a community education activist. In any great change effort there are always leaders who

step forward and lead the charge. That person, the public educator, becomes a cheerleader,

an organizer, a promoter, a recruiter, and a coordinator all in one. Get others excited about

the possibilities of reducing fires and injuries through community education, and then chan-

nel that excitement into action and involvement. Enthusiasm will get others on the team.

Continually discuss community education programs with department leaders so they stay

committed.

The toughest task is winning the support of other department members. Take the time to

listen and consider their program recommendations and recruit assistance in marketing

the program to the community.

Why is organizational support so important?

Organizational commitment is essential for success. There may be some short-term victories

without organizational commitment, but long-term, community-changing results will not

be possible.

There are several tangible benefits that come with organizational support. First, department

resources are available more readily. This includes the most valuable department resource—

its people.

Secondly, fire department leaders will help make connections with other leaders in the com-

munity. Fire chiefs are active in the community and interact regularly with other leaders. The

chief will facilitate introductions to the other leaders so the public educator can promote the

community education initiative directly to decisionmakers. In short, the fire chief can open

doors easily that otherwise might require a great deal of effort.

Finally, when the organization is supporting community education initiatives publicly it

sends a signal to other community organizations and agencies: Reducing fires and injuries in

our community is important! When your department supports community education, other

community partners will get on board.

What department actions support community education?

Organizational commitment for community education is not a one-time thing. It’s an all-the-

time effort that becomes a part of the department culture. This level of commitment takes

strong leadership from the public safety educator. It is not easy to achieve. These points are

key: 1) Community education can reduce fires and injuries effectively when used as part of

the department’s overall prevention strategy; 2) It may take months or years for community

education initiatives to be fully effective; 3) The community looks to the fire department for

leadership; and 4) Effective community education requires a partnership.

Introduction - 9

Make sure the chief understands what community education is, and what is required to

have a successful education program. Educate the chief and other decisionmakers and

leaders about community education.

The following paragraphs discuss several organizational actions that are important in order

for a community education program to be effective and to achieve its goals.

Institutionalize community education as an organizational value. Fire suppression is a

program deeply ingrained as a department value. Firefighters don't argue that fire suppres-

sion is a key mission of the department. The same should be true for community education.

Community fire and life safety education should be included in the mission statement. It

should be part of the department's budget. Job descriptions should include community edu-

cation as a required duty, and personnel should be trained as community educators. Com-

munity education should be part of the department's overall prevention strategy.

Commit department resources to the community education program. Community edu-

cation, just like any other department program, requires resources. Those resources include

money and people. Some community education initiatives require a multiyear commitment

from the department. For example, school-based education programs such as the NFPA's Risk

Watch must be used in the classroom over a period of years to be effective.

Identify the short- and long-term resources required for any community education program.

Make decisionmakers aware of all the resources required for the program when gaining their

support. This information allows decisionmakers to budget to meet ongoing needs.

The public demands that fire suppression crews be staffed adequately and have the ap-

paratus and equipment necessary to put out fires and respond to EMS emergencies. The

community educator should avoid demanding the same funding as suppression: This

will alienate the fire chief and operational personnel. Rather, work with the fire chief to

obtain the resources necessary for success while respecting the needs and roles of other

department programs, including suppression.

Community education is made a department activity. The fire departments with the most

successful community education programs all share one common strategy: every person on

the department is a community educator. This includes firefighters, code inspectors, investi-

gators, and even administrative personnel. Everyone must be involved in the overall commu-

nity education program. When this happens a multitude of resources become available.

Introduction - 10

Decisionmakers and senior ofcers are taught the process of re and injury prevention.

Senior officers should receive training on how to develop a prevention strategy which in-

cludes conducting a community risk analysis, identifying the appropriate strategies to reduce

the problems, and methods for involving the community in the prevention program.

Senior officers and department leaders find it difficult to support what they don’t understand.

Identify training opportunities such as the NFA’s Community Education Leadership and Strategic

Analysis of Community Risk Reduction courses. Similar State and local training programs also may

be available.

Encourage the senior officers and decisionmakers to take these classes as part of their

professional development. The lessons and skills they learn will be an asset to you and

the community education program.

Prevention strategies include adopting and enforcing up-to-date re safety codes and

standards, and building plans review. A comprehensive prevention program includes com-

munity education, adopting fire and life safety codes, code enforcement, and building plans

review. Education alone will not be fully effective.

Expand prevention strategies to include injury prevention. In many communities the

greatest risk to the health of the public is not fire, but rather more generally preventable in-

juries. Most departments provide some level of emergency medical services (EMS), so injury

prevention should be part of the department’s prevention mission.

The community educator should have a good relationship with the re chief. The educa-

tor must make a commitment to building and maintaining a good working relationship with

the chief. What does a good relationship involve? Here are some important considerations:

• Trust. Part of the relationship with the fire chief is mutual trust. A fire chief must be able

to trust the information being provided by an educator. Always be completely truthful,

even if it’s painful to do so.

• Mutual Respect. Respect the fact that there are more programs to consider than just com-

munity education. There are times that resources requested are not going to be available

because of other department priorities.

• Acting proactively. Look to the future and have at least a 2- to 3-year plan for the pro-

gram. Maintain a community planning process. Advanced planning helps to align depart-

ment resources more effectively for program support.

Introduction - 11

• Seek to understand before being understood. Take the time to learn about the rest of the

department’s programs and needs and then relate the education program’s needs in those

terms.

• Play by the rules. It is tempting to bend the rules and to go outside regular channels to

get things done. But this strategy breaks down mutual trust. There are always rules and

policies. Learn them and use them effectively.

• Do a few things well. Identify the highest priorities for the community through a plan-

ning process, and then attack those priorities with all the resources available so that the

program will be successful.

Summary

Success comes from building internal support for community education, understanding the

role the community educator plays in successful programs, and creating an organization that

is focused on prevention and community education. The community educator must be the

leader in this process, and be responsible for guiding and educating other people and groups.

The “five-step” process outlined in this guide is a key to success. It really works!

The public educator must complete the planning process by determining the most serious

fire and/or injury problems facing the community and the best solutions. Then he or she

must be willing to reach out to the community and work with other agencies as part of a

community team. Finally, program results must be evaluated correctly.

This guide provides you with information to develop the skills for conducting a basic but ef-

fective planning process. Through the years, the lessons and processes have proved effective.

It’s now up to you to use the planning process as the foundation for your public education

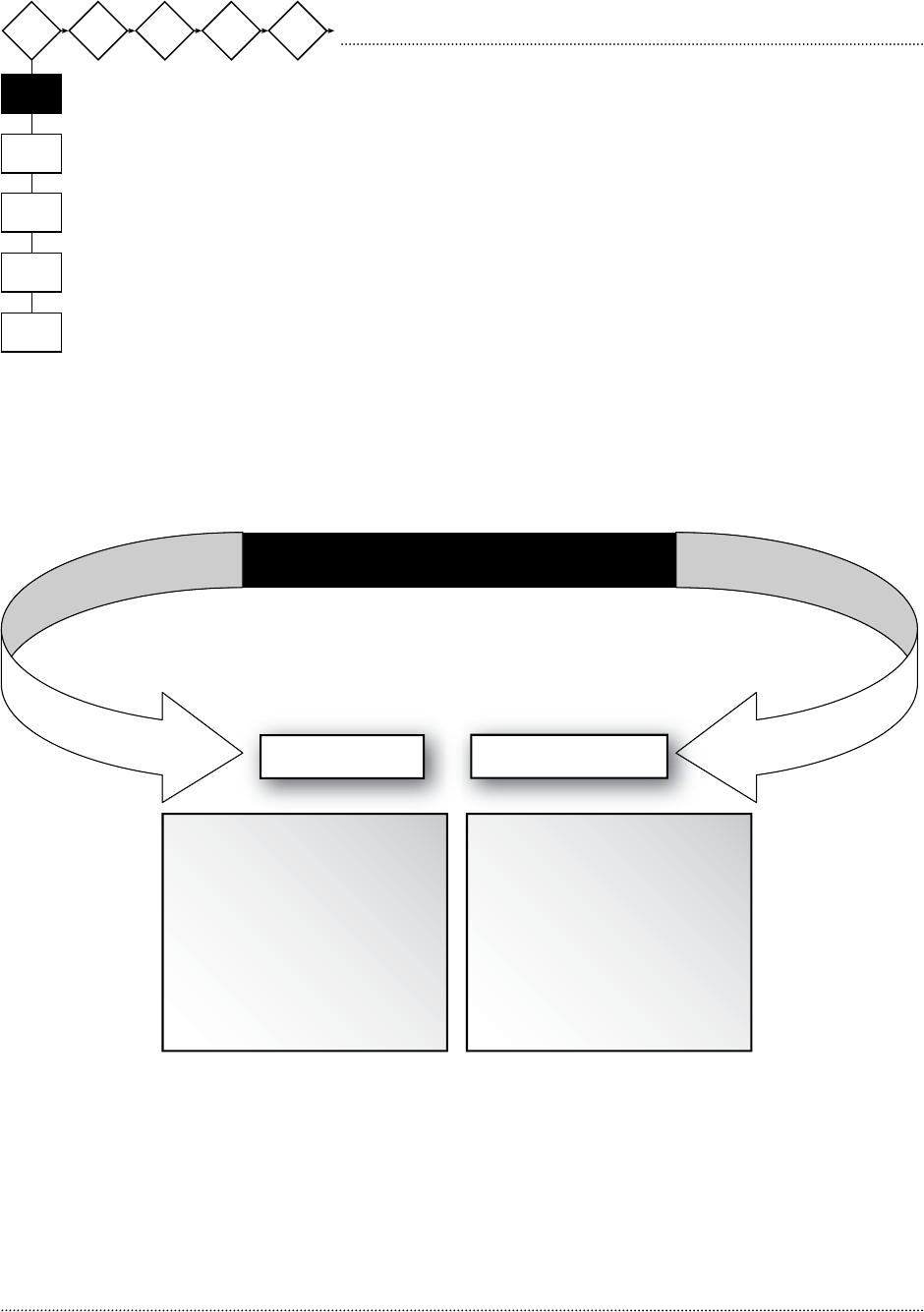

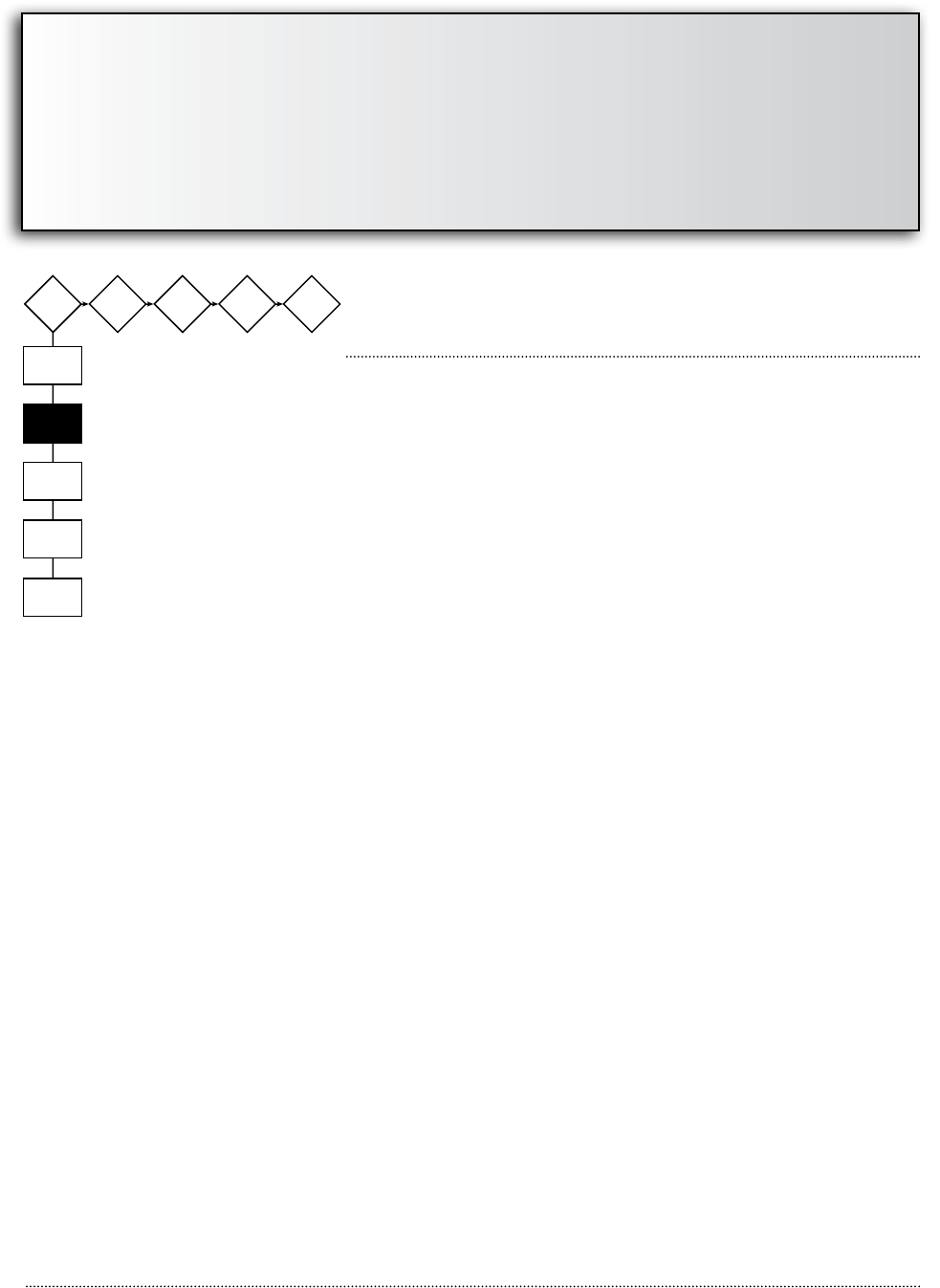

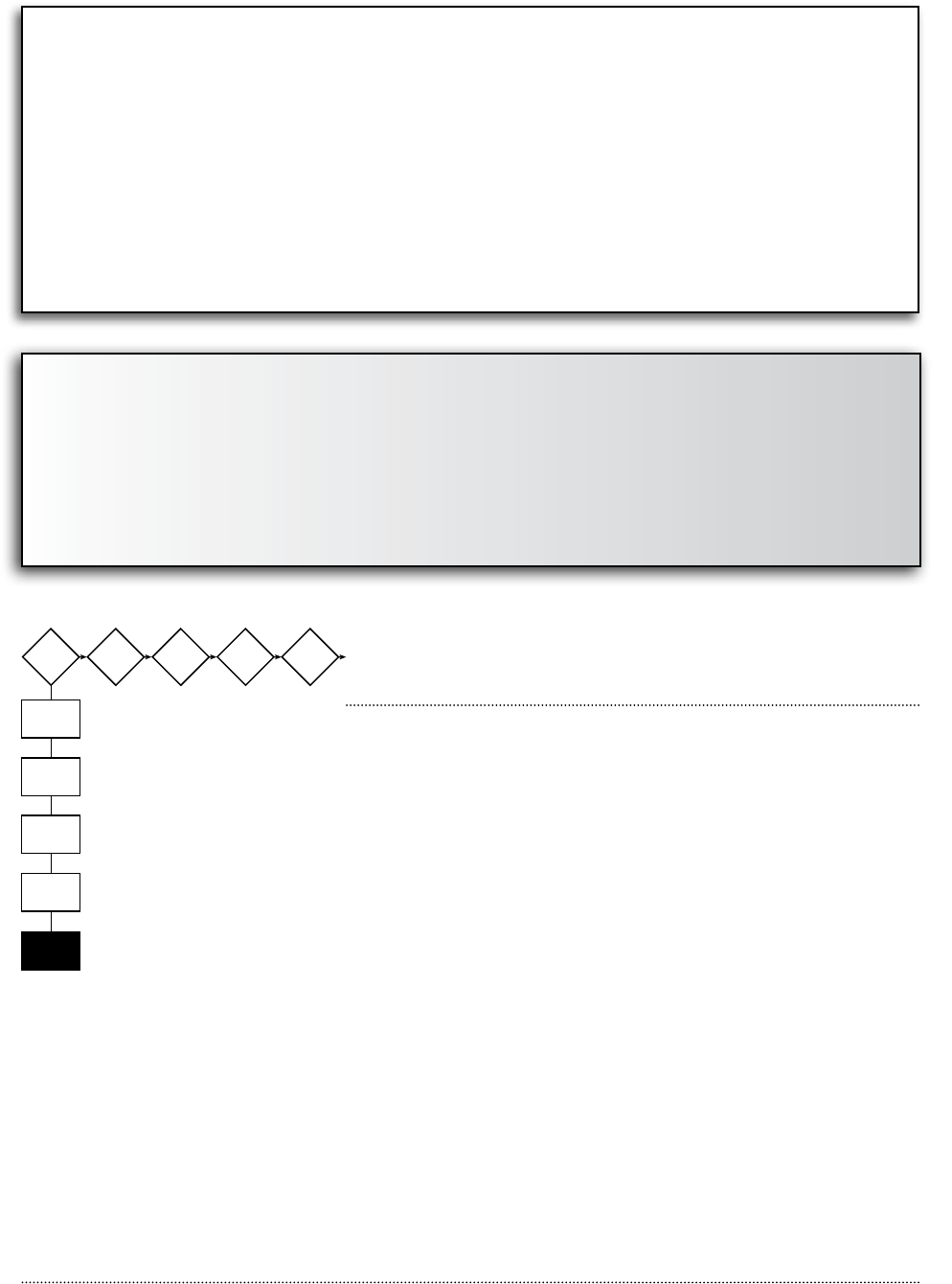

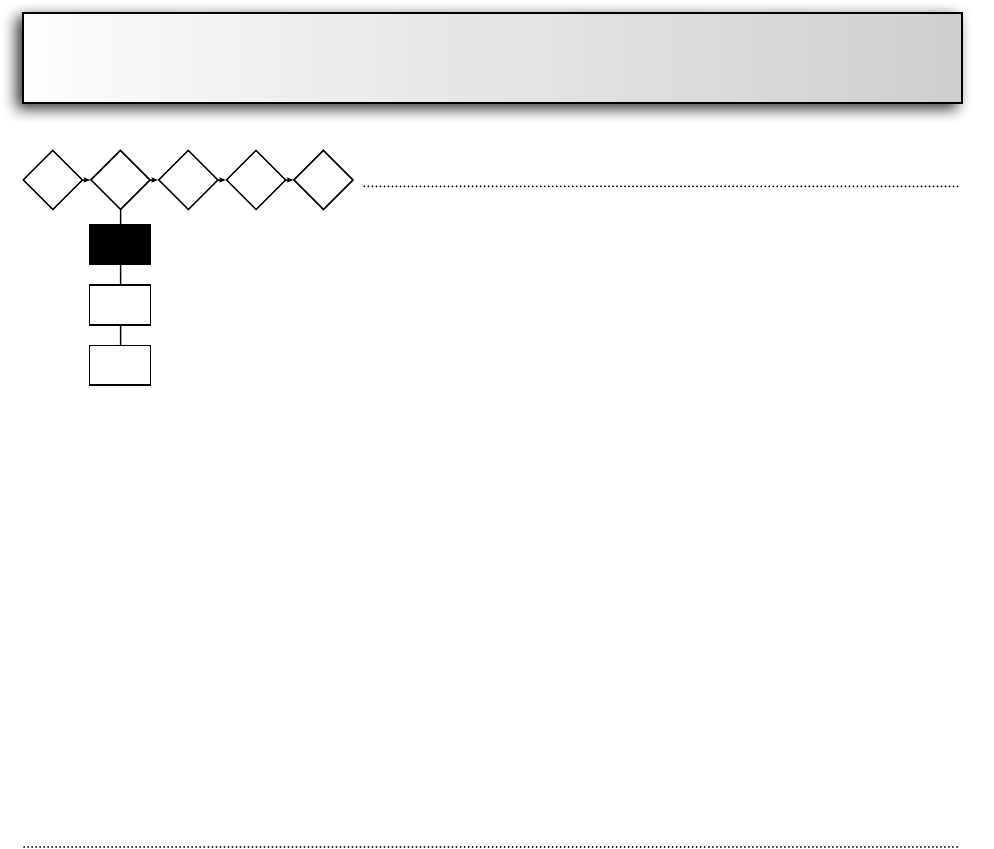

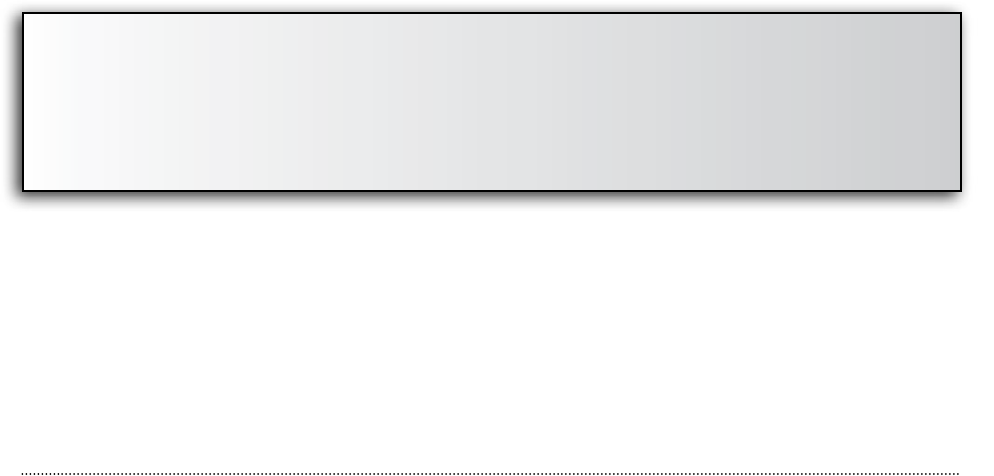

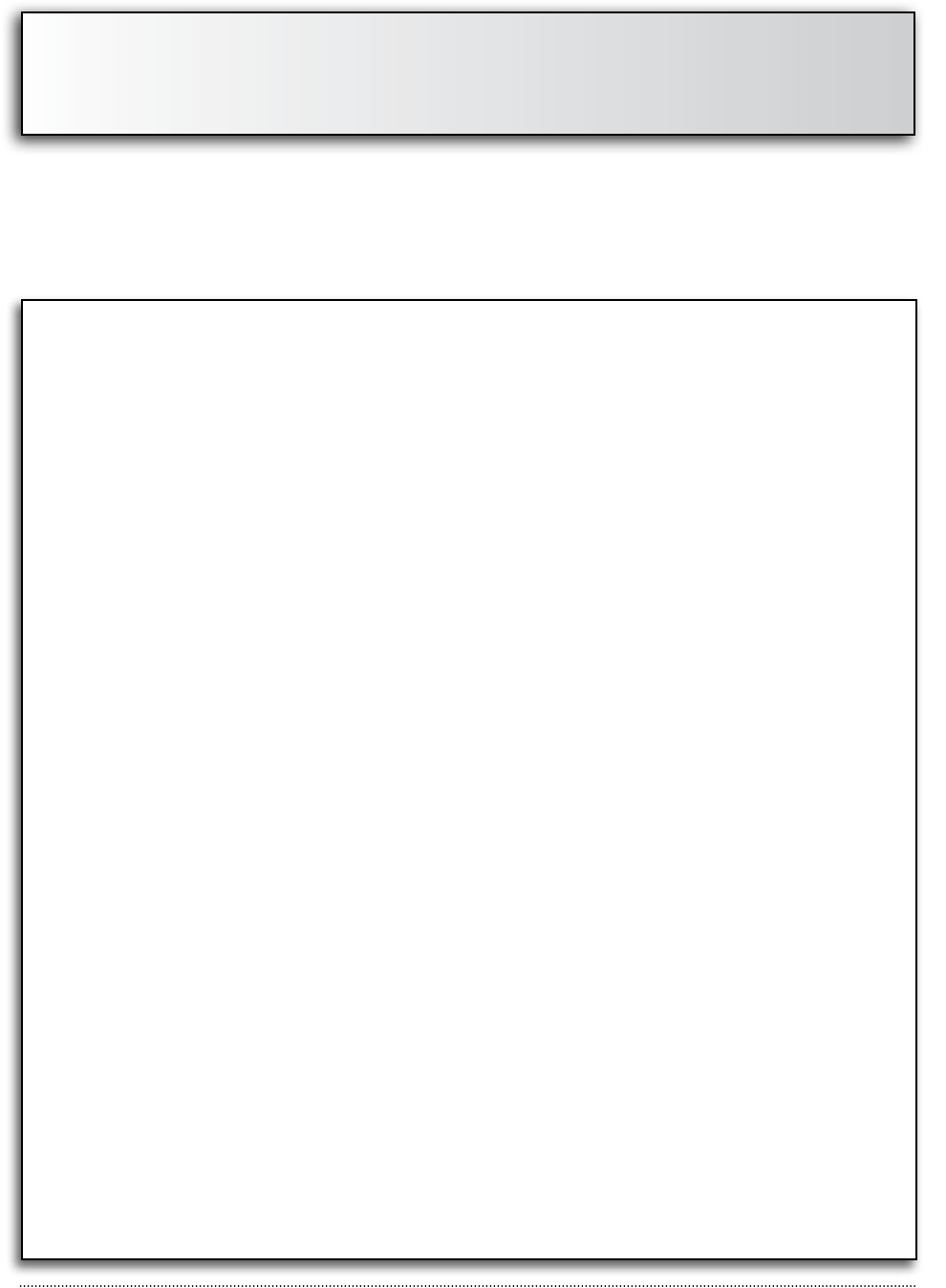

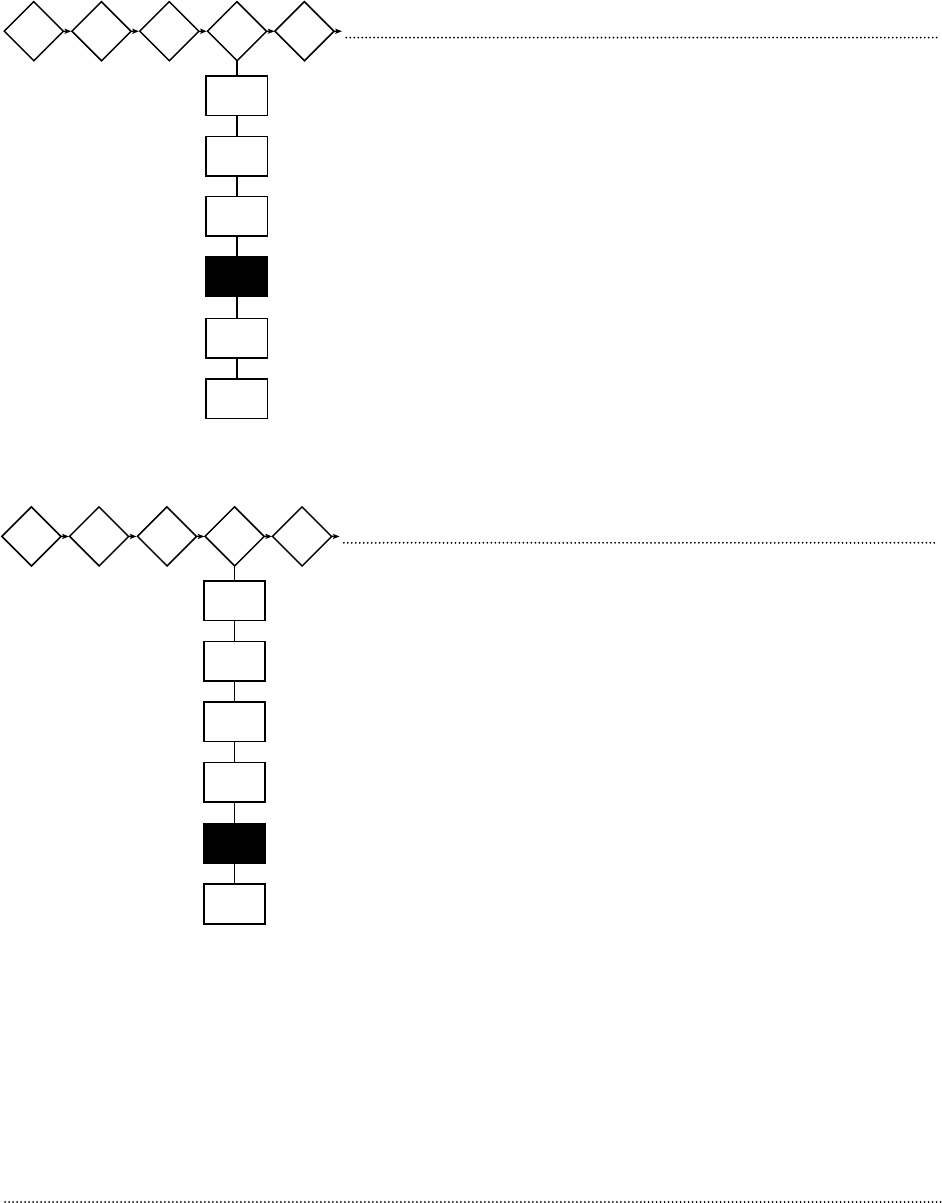

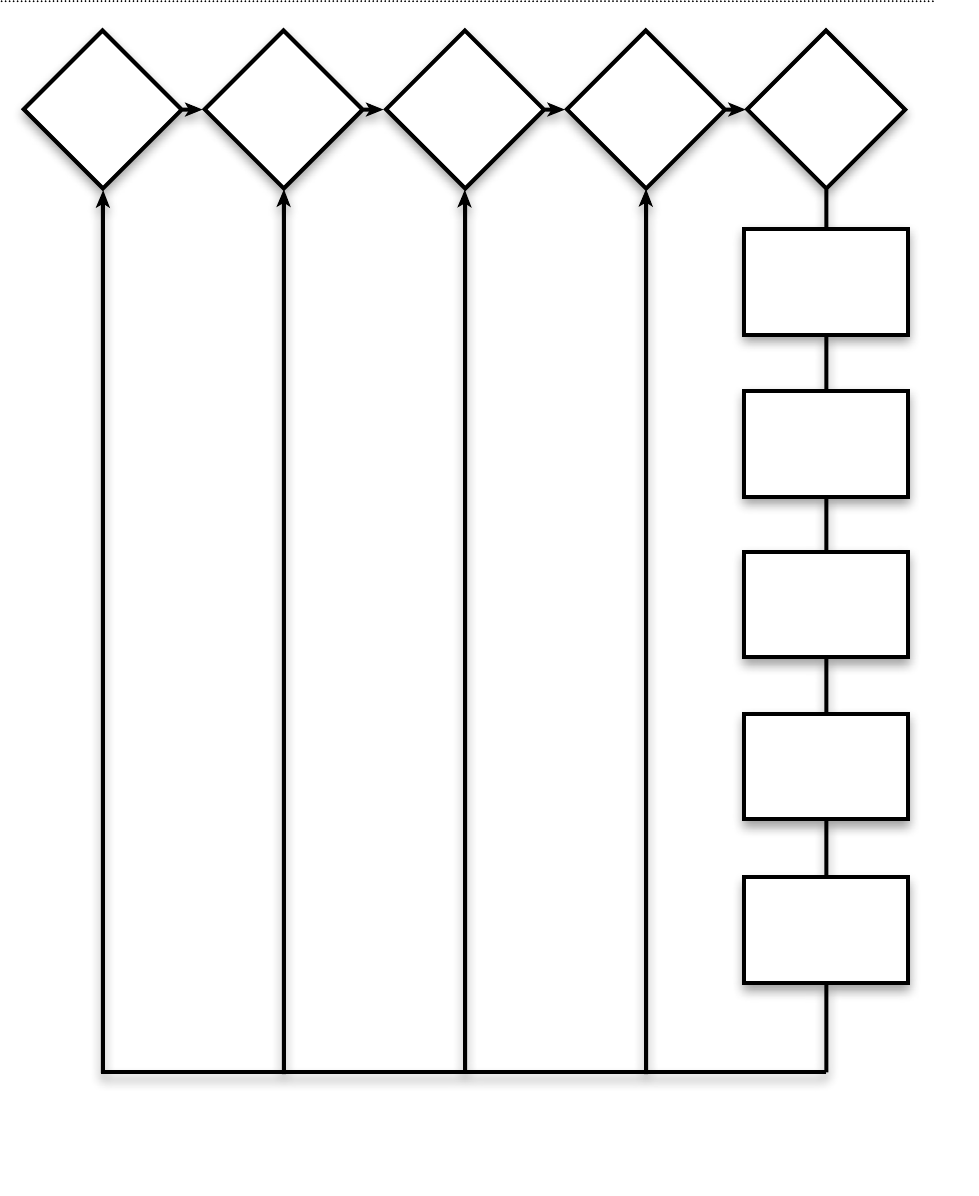

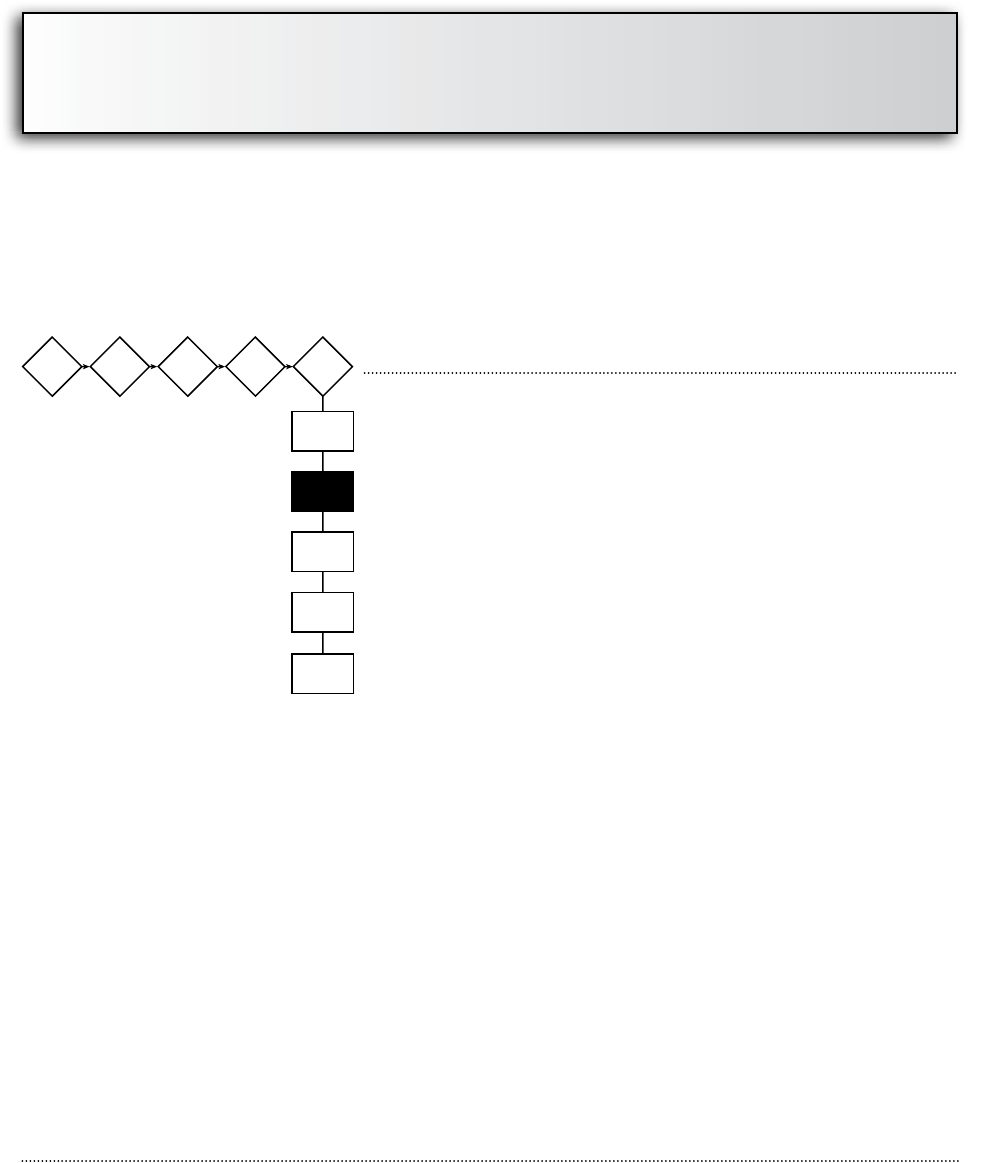

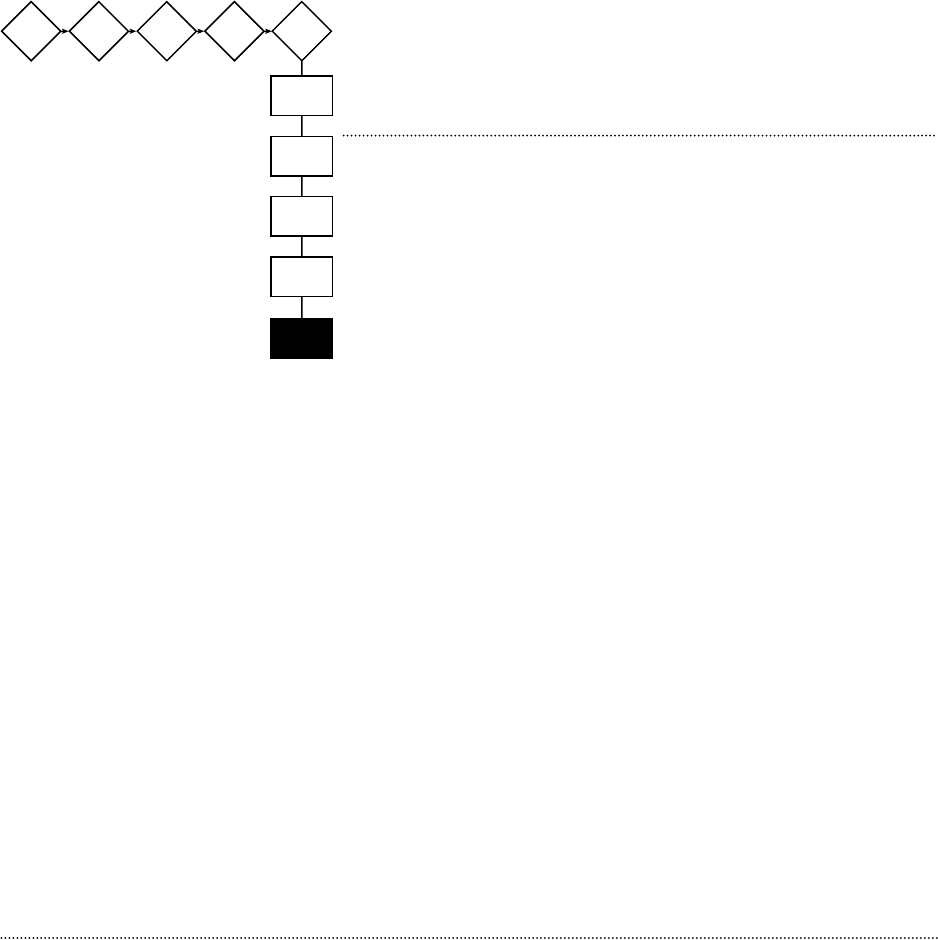

Conduct a

Community

Risk

Analysis

Develop

Community

Partnerships

Create an

Intervention

Strategy

Implement

the

Strategy

Evaluate

the

Results

Indentify Data

to be

Analyzed

Develop a

Community Risk

Profile

Write a

Problem

Statement

Prioritize

Issues

Identify Ta rget

Areas and

Populations

Step 1: Conduct a Community Risk Analysis

1-1

Chapter 1

Step 1: Conduct a Community Risk Analysis

Introduction

What is a community risk analysis? A community risk analysis is a process that identifies fire

and life safety problems and the demographic characteristics of those at risk in a community.

A thorough risk analysis provides insight into the worst fire and life safety problems and the

people who are affected. The analysis results create the foundation for developing risk reduc-

tion and community education programs.

Conducting a community risk analysis is the first step toward deciding which fire or injury

problem needs to be addressed. Risk analysis is a planned process that must be ongoing, as

communities and people are constantly changing.

Why conduct a community risk analysis? Fire and rescue departments must use facts in

order to correctly identify leading safety risks that need attention. A community risk analysis

will provide these data.

Consider this: A group of people decide to plan a trip. How will they know the best route to

take without knowing where their starting point is? Likewise, it is important to know where

a community is before beginning a community education program that will reach a risk re-

duction goal.

Too often, an objective and systematic community risk analysis is a step that is overlooked in

the community education process. Many emergency service organizations address risks based

on a perceived need for service that isn’t really there. An educator may want to teach people

about something that is not a problem, perhaps just because a particular subject is interesting.

First, it will be hard to get people to participate in an unnecessary program. Second, nothing

actually will be accomplished. This approach can be costly in terms of misdirected resources,

continued property loss, injuries, and deaths.

Examples

• An organization reads about a high occurrence of electrical fires in a neighboring com-

munity and decides to begin a campaign to address these types of fires.

However, a data analysis of its own community’s fire occurrences reveals that it has very

few electrical fires. What it does have is a large number of unattended cooking fires.

Result: Because its campaign is misdirected to electrical fires, cooking fires and related

injuries continue.

1-2

• An organization located in the northeastern United States reads of swimming pool drown-

ings occurring in the southwestern part of the country. The organization begins a safe

swimming campaign.

If this organization looked carefully at community data, it would identify that only two

swimming pool drownings had occurred in the prior 10 years. Further study would have

revealed a large number of child pedestrian injuries and deaths.

Result: Because its campaign is misdirected toward deaths by drowning, child pedestrian

injuries and deaths continue.

It is easy to become distracted from local issues by big media splashes about national hap-

penings. Don’t let that happen. Stay focused! Invest the time to conduct an objective com-

munity risk analysis. Having facts about the leading causes of risk and the people being

affected will set the stage for a successful risk reduction process.

Objectivity means using reliable data to make conclusions based on facts, not beliefs.

What does a community risk analysis include? A community risk analysis includes five

important activities:

1. Identify data to be analyzed.

2. Develop a Community Risk Profile.

3. Write a problem statement.

4. Prioritize issues.

5. Identify target areas and populations.

The analysis provides a factual overview of the risk issues, using the information obtained,

and should be used to develop a risk reduction proposal. This will produce a picture of what

is wrong and who is at risk.

1-3

Identify Data to be Analyzed

What is problem-related information?

Problem-related information identifies three things:

1. The leading causes of community risks.

2. Where problems are occurring.

3. Who is being affected by the risk.

Problem-related information is obtained by conducting research, asking questions, and mak-

ing comparisons based on quality data.

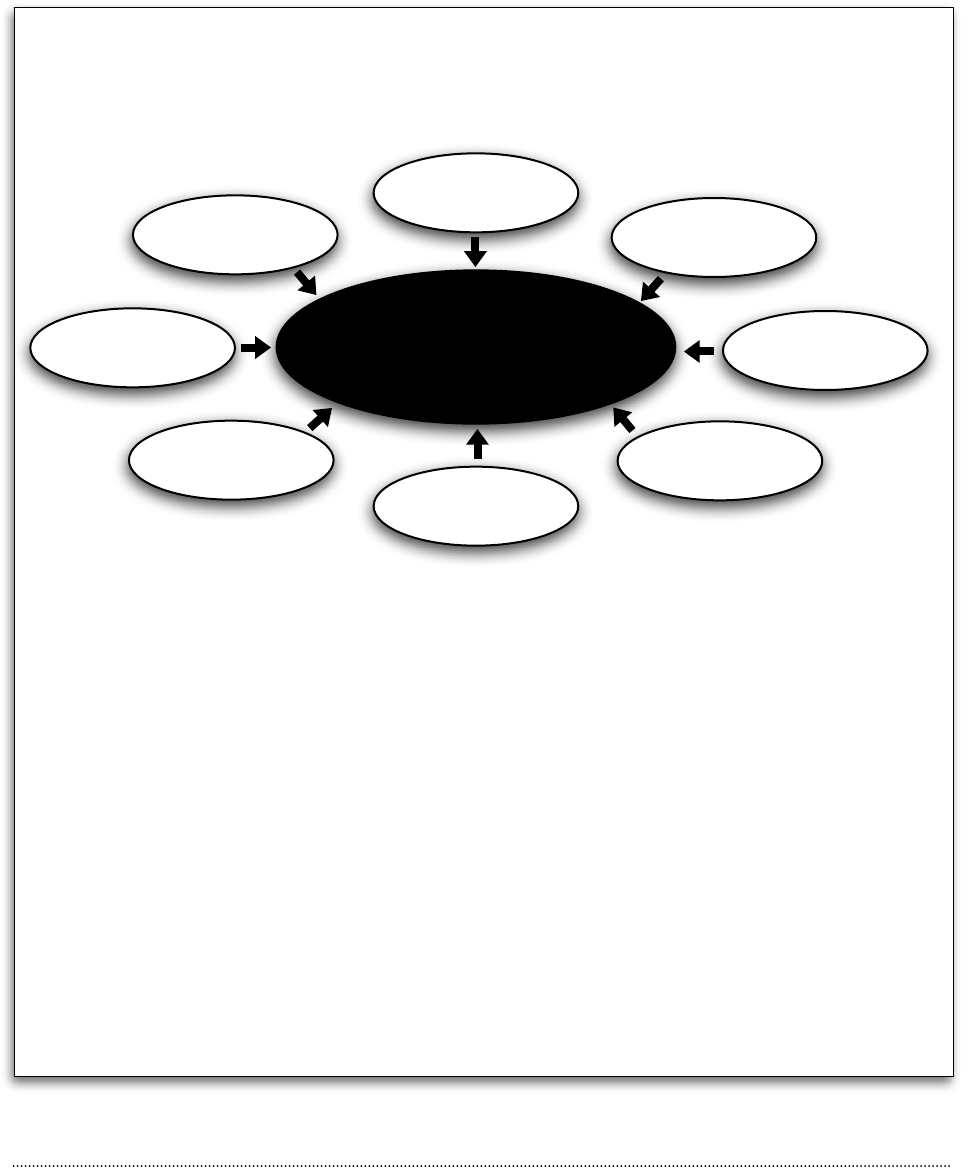

COMMUNITY ANALYSIS

PEOPLE PROBLEM

Ta rget Audience

Characteristics of

Audience

Relationship of

Audience to Problem

Nature of Fire/Injury

Problem

People Affected by Problem

Cause of Problem

Solution to Problem

Figure 1: Community Analysis.

How do you locate problem-related information?

Here is an example. A fire department in Safe City, USA, wants to examine the leading cause(s)

of fire in the community

1-4

The fire department locates valid data sources to identify the leading causes of fire in Ameri-

ca. Sources include the NFPA and the USFA. National injury data also can be sought from the

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and the National Safe Kids Coalition. Na-

tional sources are sought so a comparison can be made to State and local data. The National

Fire Data Center Web site provides community educators with published statistical informa-

tion on the national fire problem.

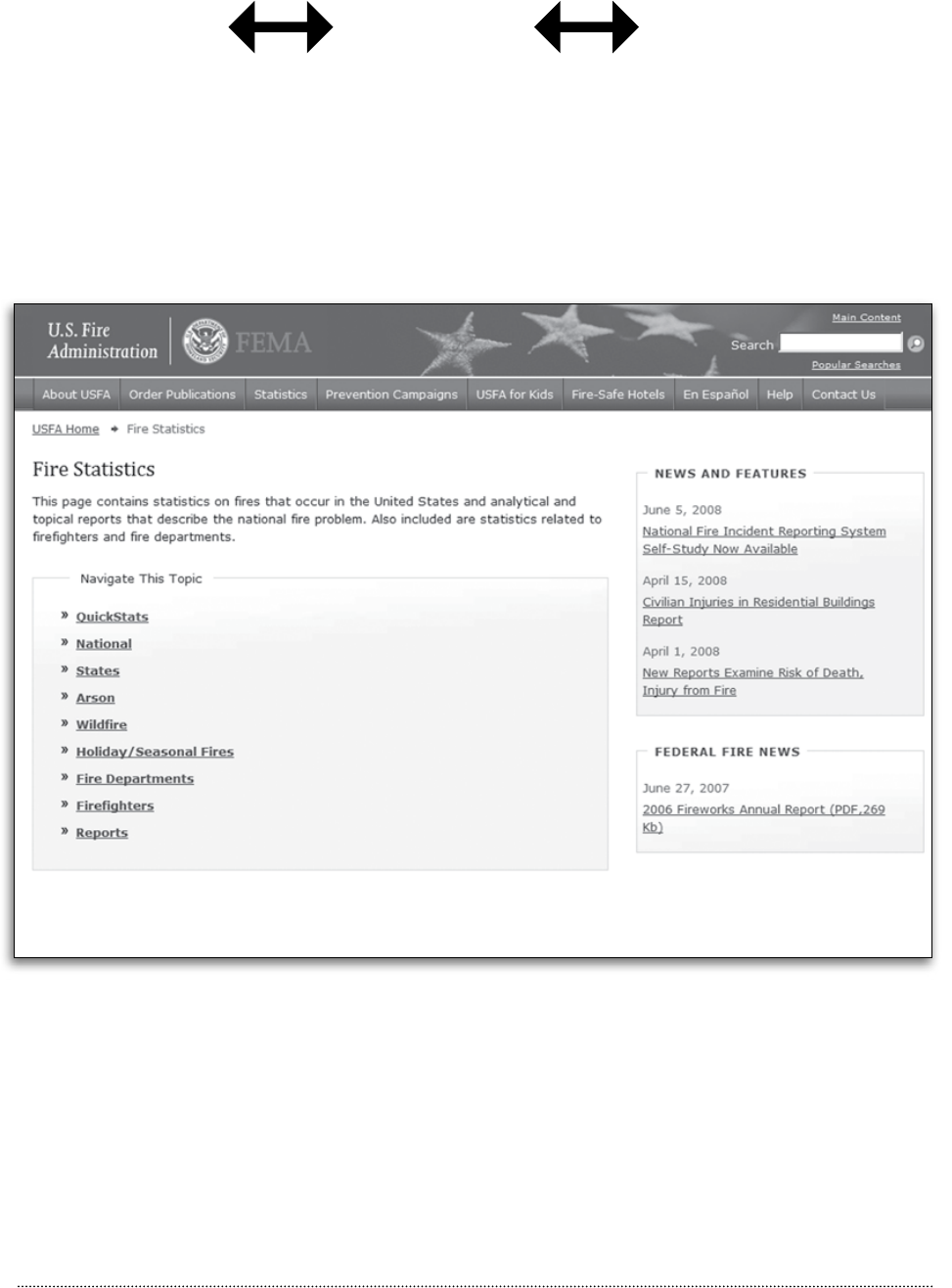

Figure 2: U.S. Fire Administration Web site.

A community educator can log onto the Internet, go to the USFA and NFPA Web sites, and

instantly review a profile of the national fire problem.

These organizations are reviewing data regularly from NFIRS. This allows them to build a

national profile of how many fires and other incidents occur, note their causes, and indicate

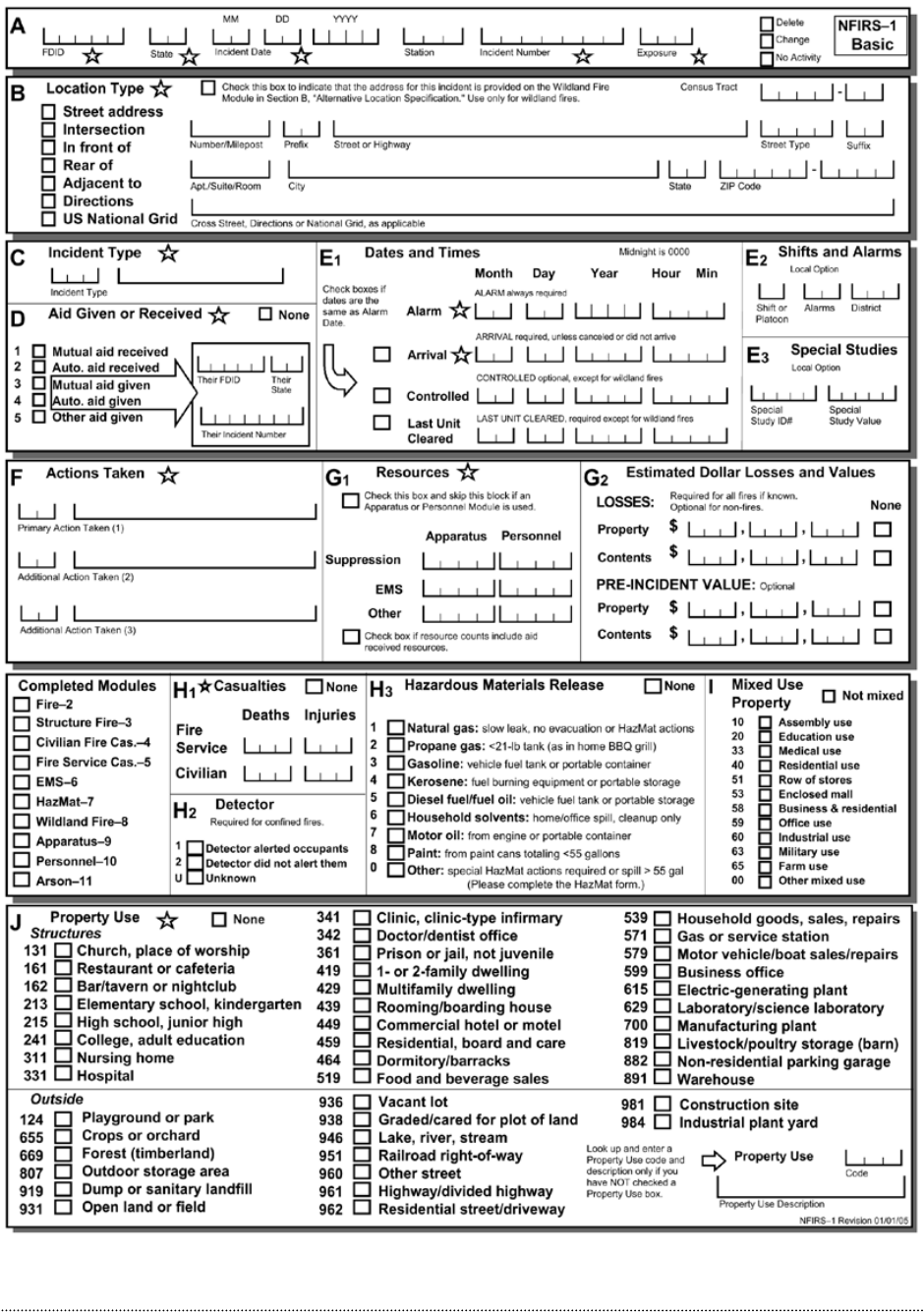

where they occur and who is affected. A copy of one page of the NFIRS report form is on the

next page.

LOCAL STATE FEDERAL

1-5

Figure 3: NFIRS Form.

1-6

The fire department locates data sources to identify the leading causes of fire in the State.

State data, usually available from the State fire marshal’s office, should be used to make a

comparison to national and local data.

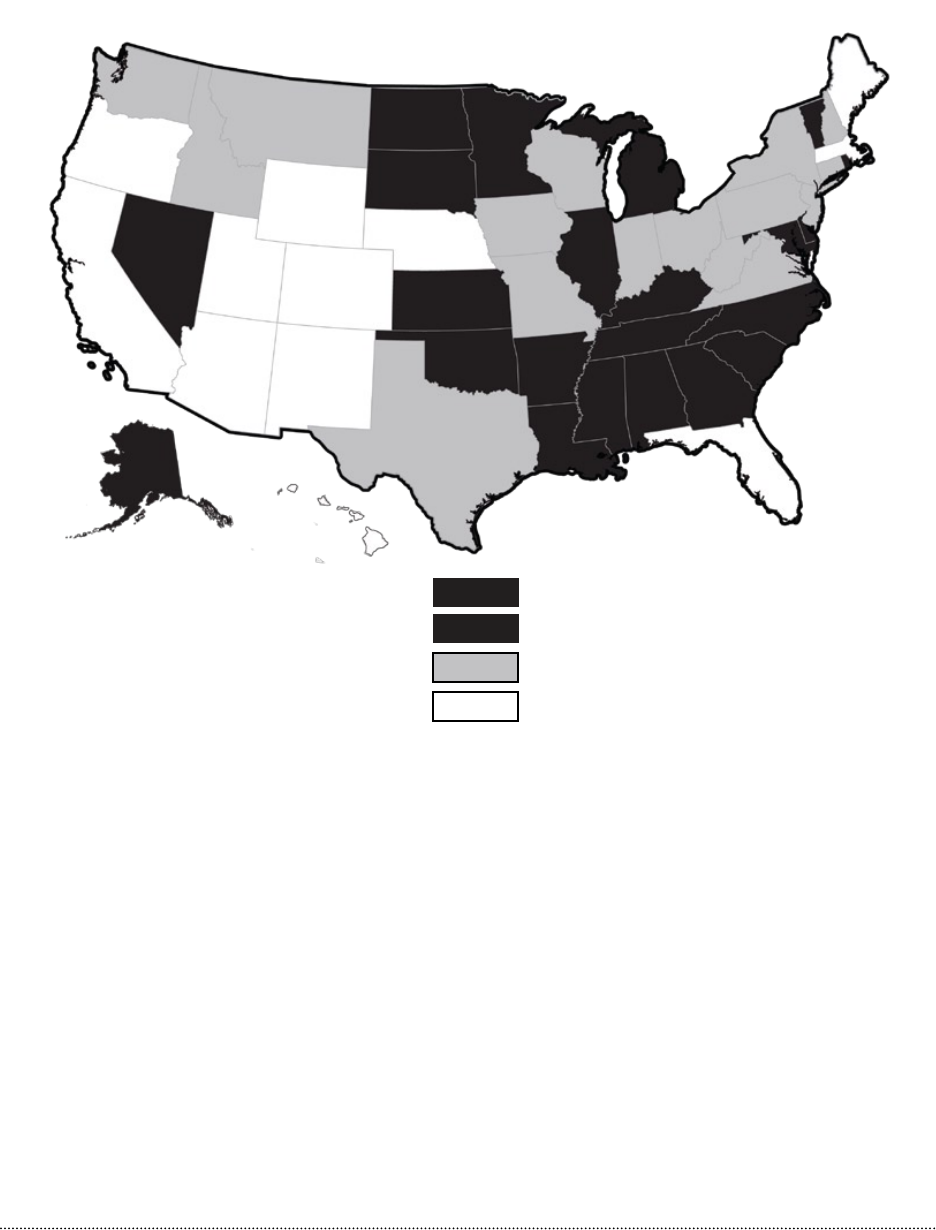

Some examples of State data include a comparison of your State’s fire deaths to those of the

whole United States. This information will provide an indicator of the magnitude of the

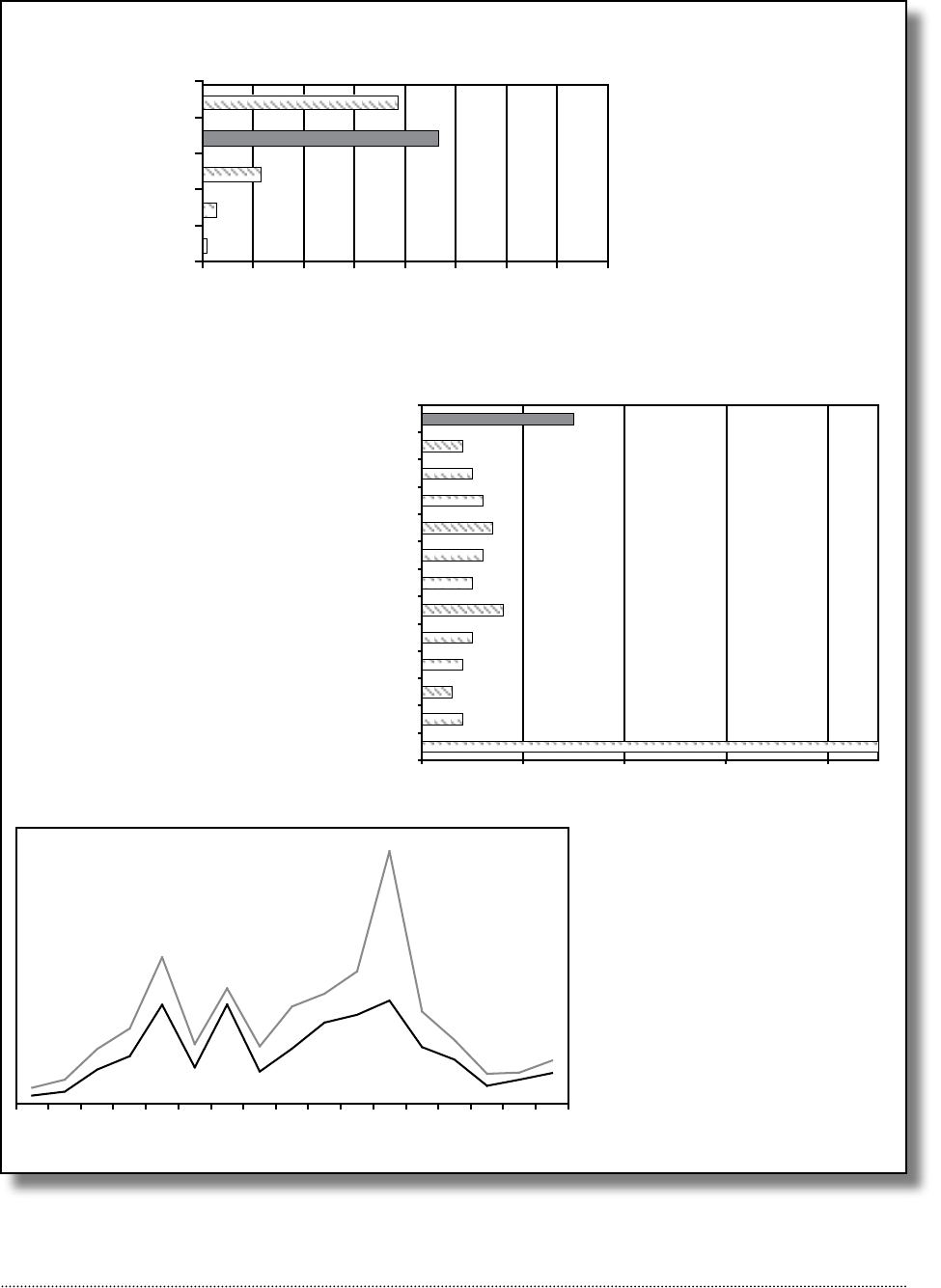

problem in your State. The bar chart in Figure 5 illustrates such a comparison.

25+ Deaths per Million Population

18-25 Deaths per Million Population

11-18 Deaths per Million Population

Under 11 Deaths per Million Population

Note: 1995 data from Indiana and Nevada are

incomplete. 1994 data are shown.

Sources: State Fire Marshals and the United States

Fire Administration.

Fire Death Rate by State in 1995

Figure 4: Death Rates by State.

1-7

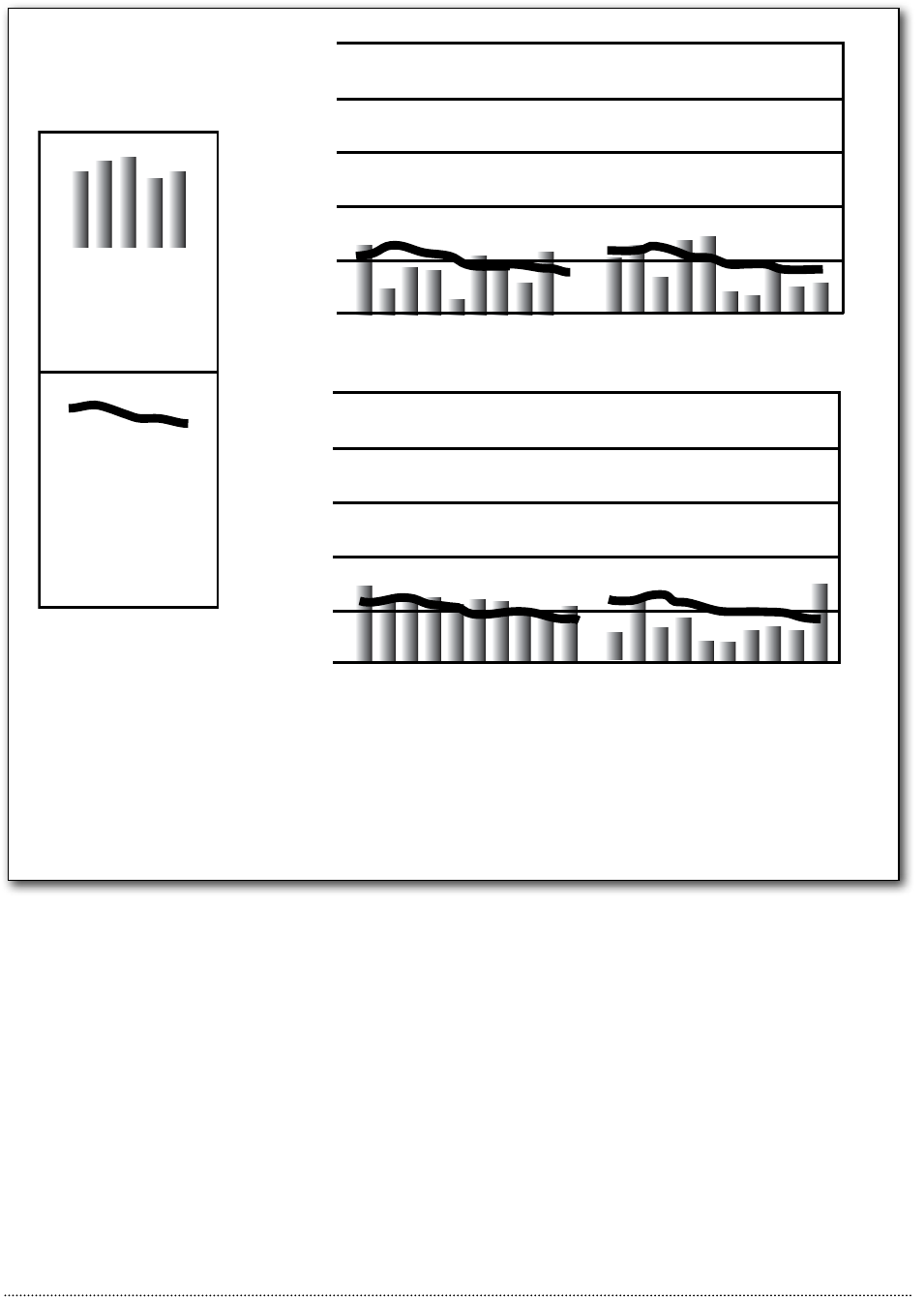

86 87 88 89 90 91 92 93 94 95 86 87 88 89 90 91 92 93 94 95

100

80

60

40

20

0

100

80

60

40

20

0

86 87 88 89 90 91 92 93 94 95 86 87 88 89 90 91 92 93 94 95

NEVADA NEW HAMPSHIRE

PENNSYLVANIA RHODE ISLAND

Fire death rate

per 1,000,000

population

Average U.S.

re death rate

per 1,000,000

population

10- Year Fire Death Rate by State

Compared to National Average

Figure 5: Comparison of State and

National Fire Deaths by Year.

1-8

The fire department examines local fire/injury experience data to identify the extent and

leading causes of community fire/injury. Sources include fire department incident records,

local hospital records, and local health department records. Additional injury data may be

available from other community organizations, such as the local Safe Kids Coalition.

It is most important to identify the leading causes of risk at the local level. Local issues may

be different from those at the State and national level. Local data are by far the most impor-

tant source of information. It is through local data that specific risks in your community are

identified.

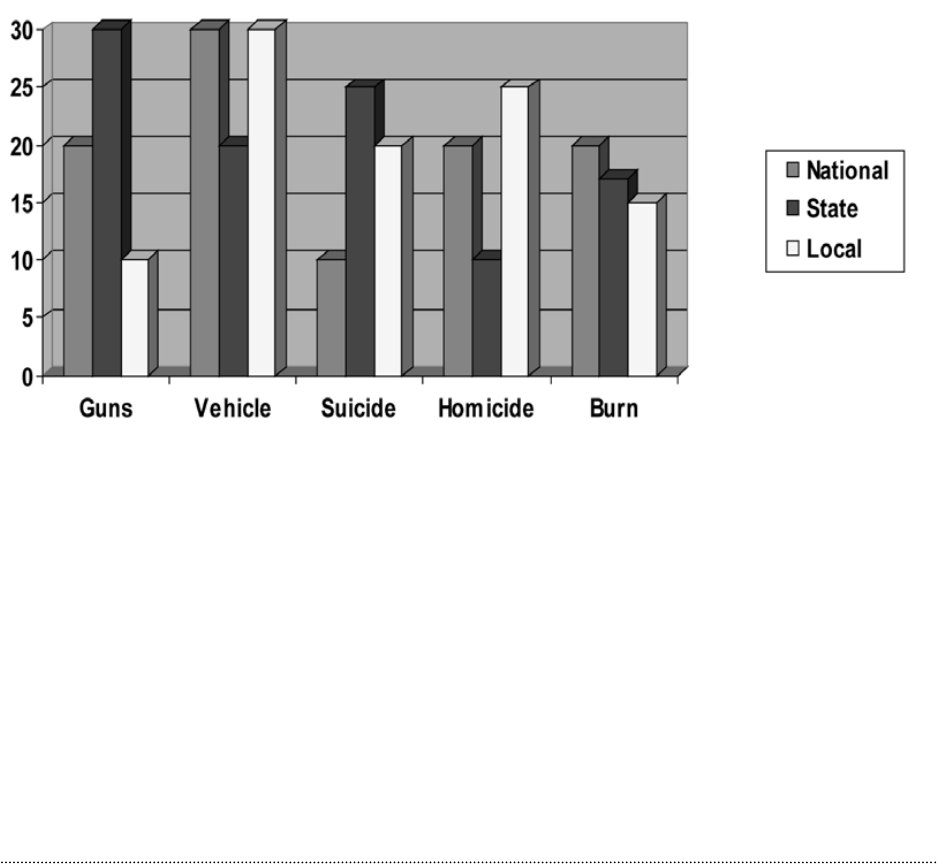

Figure 6 gives an example of local data compared to State and national data on injuries by

cause of injury.

Figure 6: Local Injuries by Cause.

The goal is to identify the leading causes of fire/injury at the national, State, and local level.

It is important to examine all levels so that comparisons can be provided to potential partners

from the local community.

If an organization does not have a formal data collection system, it is never too late to start

one! Potential sources to assist with learning how to collect data are listed at the end of this

section.

Injuries by Cause

How much local problem information is needed?

Quite a bit of information is required in order to draw accurate conclusions. Even though

national and State information is available, it is critical to develop the same type of profile at

the local level.

Examine at least 3 years (more if possible) of data. This will allow the identification of a

baseline (average) of how many times a specific incident occurs annually. The smaller the

community, the further the history search should be extended.

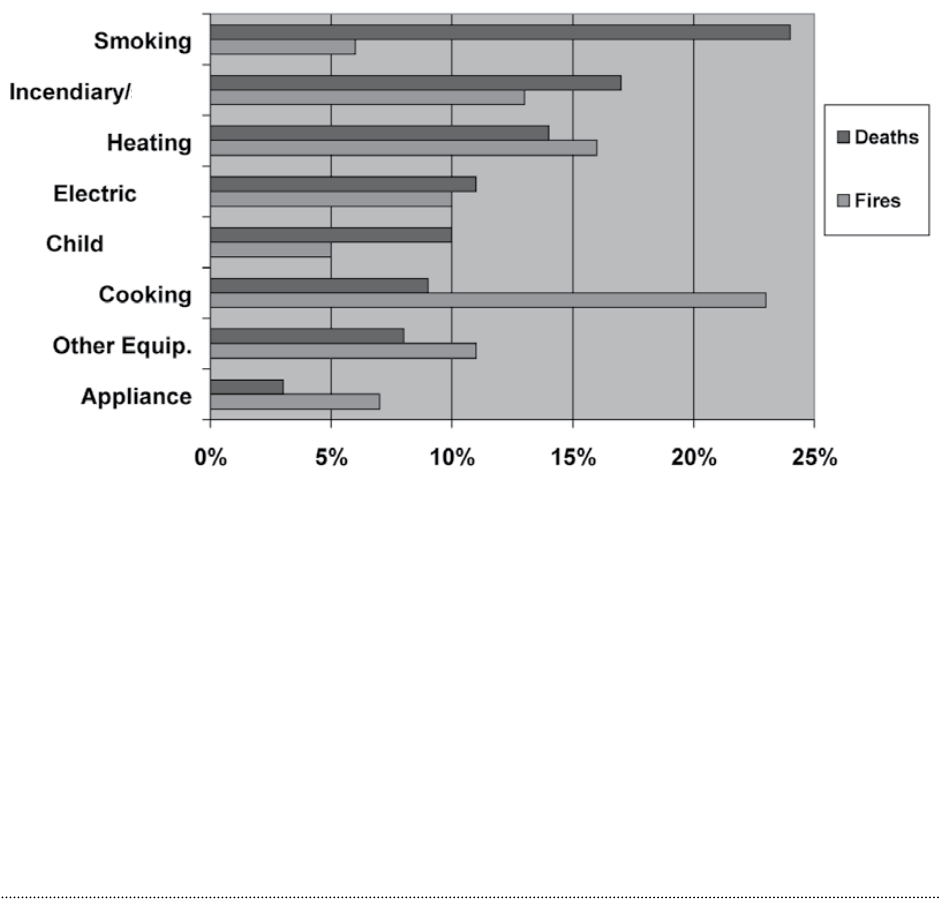

Leading Causes of Home Fires and Deaths

1993-1997 Annual Averages

Figure 7: Annual Average Comparison of Home Fires and Deaths.

It is easy to create a simple database from existing run sheets. This allows the fire department

to identify fire and injury causes and their occurrences.

For example the following activity report can be used to study the fire problem in your city.

1-9

Susp.

Dist.

Playing

1-10

Aug.

2001

Aug.

2000

Year to

Date

2001

Year to

Date

2000

SUPPRESSION

Total Incidents 150 156 1,218 1,102

Estimated Loss 6,102 265,905 854,642 657,654

Multiple Alarm Fires 0 1 1 2

Average Number of Firefighters Per Incident 7 7 8 7

Average Response Time 2:41 2:24 2:38 2:44

Average Time Spent Per Incident 19:16 23:38 22:36 26:56

Civilians Injured 0 1 7 5

Civilian Fatalities 0 0 0 0

Civilians Rescued/Revived 0 0 0 1

TRAINING

Monthly In-House Training Hours Provided 0 0 20.5 26.5

Firefighters Injured 0 0 6 2

Firefighter Fatalities 0 0 0 0

INVESTIGATIONS

False Alarms 6 4 48 40

False Alarm Arrests 0 0 1 2

False Alarm Convictions 0 0 1 2

Incendiary Fires/Fireworks 5/0 6/0 30/0 23/0

Arson Arrests/Fireworks 1/0 6/0 21/0 17/0

Arson Convictions/Fireworks 1/0 2/0 19/0 10/0

INSPECTIONS

Total Inspections 84 125 711 848

Site and Building Plans Reviewed 28 22 164 174

Citizen Complaints Received about Fire Violations 1 0 6 6

Number of Appeals 0 0 0 1

Legal Action Taken 0 0 0 0

PREVENTION/EDUCATION

Free Smoke Detectors Installed 15 6 215 236

Public Education Programs

(Children’s Village - 1; School - 0; Other 1) 9 11 134 131

People in Attendance

(Children’s Village - 30; School - 0; Other - 30) 450 340 5,890 4,935

Media Articles/Programs 6 15 74 90

’

Figure 8: Local Activity Report.

Activity Report for August 2001

Fire Department

Safe City Example

The Safe City, USA, fire department responds to 100 structure fires each year. The fire

department decides to examine 10 years of structure fire experience data to identify the

leading structure fire cause in Safe City.

The Safe City Fire Department discovers it has responded most often to fires resulting

from unattended cooking: 400 such calls over a 10-year period. To determine the aver-

age number of cooking fires per year, divide the total number of cooking fires in the

10-year study (400) by the number of years in the study (10). The result: Safe City Fire

Department experiences an average of 40 cooking fires per year.

These data can be restated as 40 cooking fires per 100 yearly structure fires (40/100, or

40 percent.

Safe City Fire Cause

Although 40 cooking fires each year may not seem like a large number, comparing the occur-

rence with all other fire causes identifies it to be the leading structure fire problem. Cooking

fires also are a frequent cause of burn injuries.

By completing this data analysis, Safe City Fire Department has identified the following in-

formation:

1-11

Safe City Fire Cause

Cooking

Other

• Theleadingcauseofstructurereisunattendedcooking.

• Theredepartmentismostlikelytodecreasethenumberofstructureresinitscom-

munity by developing a campaign to reduce cooking fires.

• ThebaselineaveragenumberofcookingresinSafeCityis40peryear.Bycomparing

next year’s incidence of cooking fires to this baseline number, the fire department will be

able to evaluate the progress of its campaign to reduce unattended cooking.

1-12

Examining at least 3 years of data (more if possible) will provide a more accurate

prole of leading risk issues.

Examining less than 3 years of data will not provide an accurate prole of leading

risk issues, and the real issues may be overlooked.

What type of local problem-related information is needed?

To conduct an objective risk analysis, the following types of local information must be ob-

tained:

• typesofincidents(res,falls,etc.);

• rootfactorsleadingtoincident(howdoesatypicalincidenthappen?);

• howoftentheincidentsoccur;

• locationoftheincidents(geographicdistribution);

• whenincidentsoccur(time,day,month);

• costoftheincidents(expense,injuries,lossoflife);and

• typesofincidentshappeningmostfrequently.

This type of local information can be displayed like the examples on the following page in

order to analyze the information and make decisions about local problems.

1-13

Figure 9: Examples of Local Data Displays.

0.9

2.7

11.4

46.5

38.6

01020304050607080

Other

Vehicle

Residential

Percent

0 10 20 30 40

Unknown

Exposure

Natural

Other Equipment

Other Heat

Open Flame

Appliances

Electrical Distribution

Cooking

Heating

Careless Smoking

Children Playing

Incendiary/Suspicious

678910 11 12 123 45 6 7 8910

Cooking Fires

Non-cooking Fires

AM PM

Dollar Loss By Property Type

Causes of Fires

When Incidents Occur

Nonresidential

Outside

Percent

1-14

Conducting a comprehensive analysis of risk helps to ensure selection of the “pri-

ority” issues.

Examining only one area (such as expense) may not provide enough information

to make an objective decision on what issue to address.

What is a community risk prole?

A community risk profile is an overview of the information gathered about the

community. It can serve as an introduction to a problem statement. A community

profile should include the following information:

• demographicdescriptionofcommunity;

• demographicdistributionofhigh-riskpopulations;

• briefdescriptionofselectedre/injuryriskissue;

• publicperceptionoftheproblem;

• existingmythsabouttheproblem;

• politicalsupportfortheissue;and

• resourcescurrentlyavailabletoaddresstheriskissue;

Develop a Community

Risk Prole

A community profile does not have to be a lengthy report. A paragraph or two for each sec-

tion is enough. The community profile leads a reader to the problem statement. Several pro-

files may need to be developed, one for each targeted risk selected.

Data collected for the local area can be summarized in charts that represent a demographic

profile. The following chart details the demographics for one county in terms of age, sex,

and income.

1-15

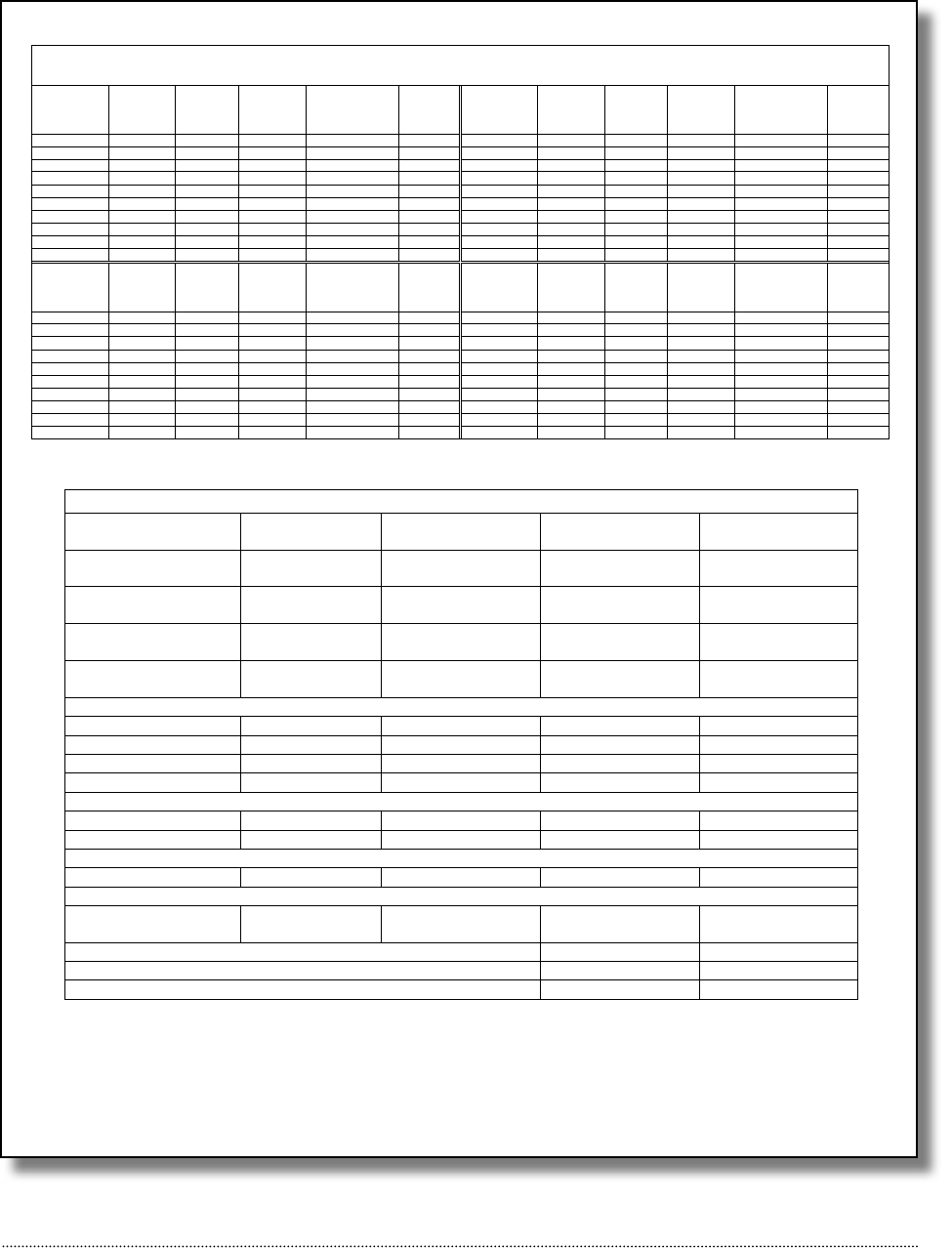

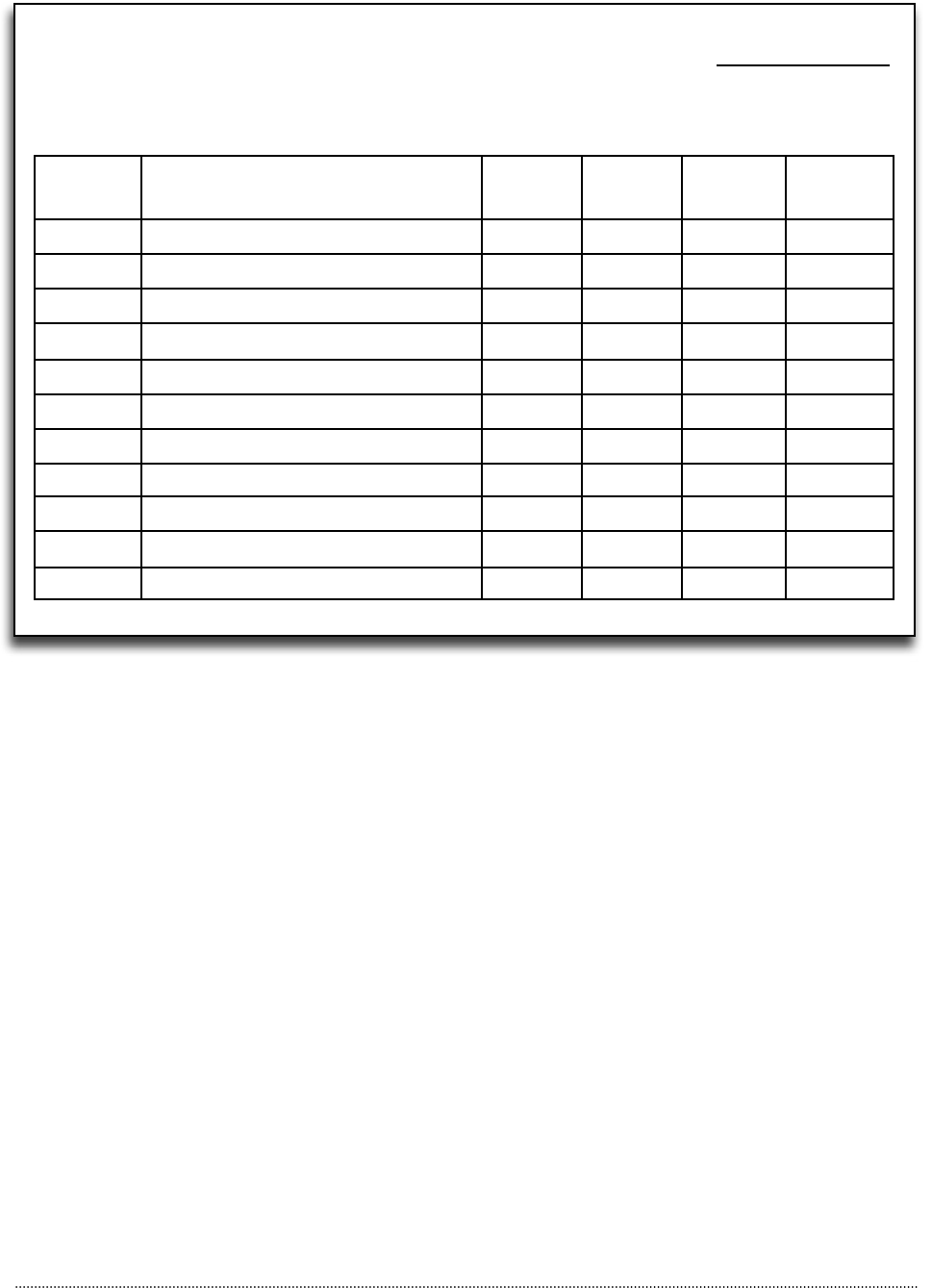

Prole of Health Status Indicators

Figure 10: Local Demographics Example.

Demographics

Males Females

COUNTY

# ALL

RACES

%

WHITE

%

AFRICAN-

AMERICAN

%

NATIVE

AMERICAN

%

ASIAN

COUNTY

# ALL

RACES

%

WHITE

%

NATIVE

AMERICAN

%

ASIAN

ALL AGES 2,961 98.5 0.1 1.3 0.0 ALL AGES 2,964 98.2 0.1 1.6 0.1

< 1 41 93.9 0.7 5.4 0.0 < 1 33 98.3 1.0 0.0 0.7

1 to 4 147 93.5 0.5 6.0 0.0 1 to 4 154 93.2 1.1 5.2 0.5

5 to 9 246 98.0 0.0 2.0 0.0 5 to 9 203 97.0 0.0 3.0 0.0

10 to 14 280 99.3 0.0 0.7 0.0 10 to 14 268 98.9 0.0 1.1 0.0

15 to 19 217 97.7 0.0 2.3 0.0 15 to 19 198 98.0 0.0 2.0 0.0

20 to 44 935 98.2 0.2 1.5 0.1 20 to 44 886 97.5 0.2 2.2 0.1

45 to 64 657 99.8 0.0 0.2 0.0 45 to 64 648 98.9 0.0 1.1 0.0

65 to 74 243 99.6 0.0 0.4 0.0 65 to 64 294 99.7 0.0 0.3 0.0

75 + 195 100.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 75 + 279 100.0 0.0 0.0 0.0

STATE

# ALL

RACES

%

WHITE

%

NATIVE

AMERICAN

%

ASIAN

STATE

# ALL

RACES

%

WHITE

%

NATIVE

AMERICAN

%

ASIAN

ALL AGES 1,586,887 83.0 7.7 8.1 1.2 ALL AGES 1,666,742 82.9 7.7 8.1 1.3

< 1 21,371 78.4 10.1 10.0 1.5 < 1 20,090 76.8 10.4 10.4 2.4

1 to 4 100,081 78.0 10.3 10.0 1.7 1 to 4 96,344 77.5 10.6 10.3 1.6

5 to 9 122,245 77.6 10.1 11.1 1.2 5 to 9 116,596 77.3 10.2 11.1 1.4

10 to 14 132,867 77.9 9.3 11.5 1.3 10 to 14 124,696 77.1 9.7 11.8 1.4

15 to 19 123,129 78.9 9.3 10.5 1.3 15 to 19 116,201 78.6 9.6 10.5 1.3

20 to 44 590,427 82.5 8.2 7.6 1.7 20 to 44 589,875 82.0 8.4 7.9 1.7

45 to 64 317,486 87.8 5.2 6.2 0.8 45 to 64 340,946 86.9 5.6 6.4 1.1

65 to 74 109,361 89.8 4.3 5.5 0.4 65 to 74 133,876 89.0 4.9 5.6 0.5

75 + 70,141 90.0 4.5 5.3 0.2 75 + 128,773 90.0 4.6 5.2 0.2

Income/Poverty

Income Levels County

Number

State

Number

County

Rate

State

Rate

Income < 100%

Poverty

523 527,088 8.8% 16.25%

Income < 150%

Poverty

1,170 884,987 19.7% 27.2%

Income < 185%

Poverty

1,646 1,070,444 27.8% 32.9%

Income < 200%

Poverty

1,895 1,242,886 32.0% 38.2%

Poverty by Age Groups

Age 0-17 162 189,553 9.7% 21.7%

Age 18-64 243 247,597 7.5% 14.2%

Age 65-74 31 32,837 5.9% 13.5%

Age 75 + 100 58,620 21.2% 24.1%

Income

Per Capita Income $18,667 $17,610 -- --

Median Family Income $31,279 $28,554 -- --

Unemployment

Unemployment Rate 67 57,867 2.4% 3.6%

Household

# Female-Headed

Households

74 87,945 -- --

Nursing Facilities County Number State Number

Beds per 1,000 Elderly (Age > 75 yrs) 131 185

Patient Rate per 1,000 Elderly (Age > 75 years) 115 144

%

AFRICAN-

AMERICAN

%

AFRICAN-

AMERICAN

%

AFRICAN-

AMERICAN

1-16

What is a problem statement?

A problem statement provides a fact-based overview of the problem and who is af-

fected by it. It also provides a vision of what the organization proposes to do about

the problem.

Here is an example of a problem statement developed in Safe City:

Write a Problem Statement

Safe City Example

Community Risk Prole

Safe City, USA, population 20,000, is a small but densely populated community located

in the southeastern United States. The town grew from a small village to its present size

beginning in the early 1900s. Most homes are more than 30 years old and are of ma-

sonry construction.

Although the railroad industry once thrived in Safe City, most residents now commute

to larger cities for work.

Safe City is an aging community, in terms of both people and properties. A significant

percentage (30 percent) of Safe City’s citizens are retired. Many reside in city-owned

housing units. A significant portion of the older adult population has difficulty with

mobility, hearing, or sight. Most live on a fixed income.

Unattended cooking is the leading cause of fire and fire-related injury in Safe City: 40

percent of both structure fires and related injuries are caused by this risk. Half of the

fires (an average of 20 each year) occur in the homes of older adults living in city-

owned housing units.

During a recent survey conducted by the fire department, only 10 percent of the older

adult population could identify (or guess) that cooking was the leading cause of fires in

Safe City. Most of the older adults stated they were safe from fire while in their homes.

The community of Safe City is very supportive of its older adult population. Although

progress on issues related to the elderly is sometimes slow, the local housing authority

plans, in response to projected community demographics, to double the number of

housing units for older adults over the next 15 years.

1-17

Safe City Example

Problem Statement

Unattended cooking causes 40 percent of fires and fire-related injury in our communi-

ty. Half of these cooking fires (an average of 20 each year) occur in the homes of older

adults who reside in city-owned housing units. Interviews with fire victims identify

that most fires occur because the cooking process has been left unsupervised.

The Safe City Fire Department proposes the development of a community-based cam-

paign to address cooking fires among the older adult population living in city-owned

housing units. This proposal is based on the following factors:

• Thereisahighoccurrenceofcookingresandre-relatedinjuriesatthecomplex.

• Thecommunityandhousingauthorityaresupportiveoftheolderadultpopulation.

• Thereisarealisticpossibilitythatsuchaninterventionwillbesuccessful.

• Asuccessfulcampaigncanserveasamodelforfuturecitywideefforts.

Done well, the community risk profile and problem statement will provide a factual

rationale of why the selected risk issue should be addressed.

Share the document with the community and convince others to join the team! A

poorly written problem statement (lacking facts) may damage your organization’s

credibility and result in less support for your proposed effort.

Prioritize Issues

How should the priority risk issue be decided?

Making an objective decision on which risk issue to address is a process that takes

time, effort, and patience. It is a decision that must be governed by local need. Fol-

lowing an organized process leads to selecting the risk issue that most needs atten-

tion as the priority risk issue.

These factors can influence a fire department’s decision to select a particular risk

issue:

1-18

• highinjury/fatalitystatistics;

• highdollarloss;and

• rapidincreaseinfrequencyofoccurrence.

Once an idea has developed about a particular risk issue. It is time to examine the

second phase of community risk analysis: people and community information.

Relying solely on problem-related data wouldn’t provide enough information to

formulate a risk reduction campaign. Additional factors should be considered.

What is people- and community-related information?

People- and community-related information is based on demography. Simply stated, demog-

raphy is the study of people and their environments.

Examples of demographic information:

• housinginformation:numberofhomesinthecommunity;typesofproperties;owner

occupied/rental units; general condition of structures; age of homes, etc.;

• peopleinformation:numberofresidents;populationdensity;age/gender/educationlev-

els; family structures; disability types, etc.; and

• economicinformation:familyincomes;individualmedianincome;overallcommunity

economic projections; number of people in poverty; number of people getting financial

assistance, reduced rent, or free or reduced lunch.

Demographic information can be gleaned from both formal and informal sources.

Formal sources may include local planning and community development offices, the Census

Bureau, the Chamber of Commerce, economic development offices, hospitals, and health

departments.

Informal sources may include local schools and Head Start centers, women’s shelters, assisted

living facilities, day care centers, community associations, social services, and reports by

clergy and established community leaders.

Comparing problem-related information with community demographics helps identify who

is most at risk, what factors place them at risk, and where a risk reduction campaign should

be directed.

1-19

Safe City Example

Safe City, USA, identified these facts about its cooking fire problem:

• Mostcookingres(50percent,infact)occurinthehomesofolderadultswith

limited incomes who reside in city-owned housing units.

• Mosthousingunitsarelocatedinthecenterportionofthecommunity.

Invest the time and effort to learn about the community. Find out who is most at

risk from the selected risk issue. The success of the program will depend upon it.

Omitting this step (or not performing a quality analysis) can result in future ef-

forts not being directed at the correct target population.

What factors place people at greater re/injury risk?

Some population types have a disproportionately higher rate of morbidity and mor-

tality. (Morbidity refers to injuries and mortality refers to deaths.) Several factors

increase the risk level of a population segment:

• Age:childrenunderage5andadultsoverage65.

• Disability,includingcognitiveanddevelopmental,mobility,visual,andhearing.

• Socioculturalandeconomicstatus.

• Gender:Maleshistoricallyexhibithigherreandinjurymorbidityandmortality

rates.

• Languageandcommunicationsbarriers.

Identify Target Areas and

Populations

1-20

Several national organizations have conducted research on high-risk populations.

Apply their conclusions to your community. References are listed at the end of this

section.

Making assumptions about high-risk populations can be a dangerous strategy. Guess-

ing which interventions will work among various groups of people may result in

the inability to reach this audience effectively.

A disability can affect a person’s ability to react and respond effectively to an emergency in

progress. Disabilities can affect any population.

Cognitive and developmental disabilities refer to a person’s inability to process information.

Mobility refers to a person’s ability to move about. Vision and hearing refer to the ability to

process sight and sound. Poverty generally increases the risk of fire and injury.

Social and cultural diversity are realities in all communities. Changing family structures, peer

influences, and language diversity are all examples of social and cultural issues that must be

considered when planning to address risk.

A person’s vulnerability to risk can dramatically increase when several of the above-listed

factors apply to that person.

Example: A visually-, mobility-, and hearing-impaired older adult living in poverty will be at

substantially increased risk of unintentional injury or fire.

Once a specific risk issue has been identified, the affected populations profiled, and the loca-

tion of occurrences plotted, the next logical step is to learn why the risk exists.

This is the time to consider the sequence of events and root factors that led to the existence

of the selected risk event.

1-21

Why examine the events and root causes that led to the problem?

An effective risk reduction intervention requires investing the time to obtain facts about what

is causing the local risk in order to create an objective community profile and problem state-

ment.

Event sequencing and root factor exploration can be conducted in two ways:

1. If a good incident reporting system is available, the data may be obtained there.

Example: NFIRS 5.0 reporting software includes a section for human actions contribut-

ing to an event.

2. If reporting system data are not available, an organization may decide to conduct post-

incident interviews with victims to determine actions that led to an event.

Interviewing people who have experienced a fire or injury provides valuable insight into

why it is occurring.

Effective research is accomplished by asking the question “Why?”

1-22

Safe City Example

The Safe City Fire Department found that older adults who left food cooking unat-

tended on the stove caused most cooking fires. The fire department interviewed 25

older adults who had experienced this type of fire.

A profile of the typical sequence of events and root factors leading to the local cooking

fire problem identified the following elements:

• Apersonbeginsthecookingprocess,usuallyonthestovetop,andturnstheheat

on high. Why? Poor eyesight causes the person to have trouble seeing the control

setting.

• Thepersonleavesthekitchenwhilecookingforvariousreasons(telephone,tele-

vision, bathroom, etc.). Why? The person leaves the room intending to come right

back but gets sidetracked and forgets the stove is on (e.g., starts watching televi-

sion or talking on telephone).

• Theunattendedpanignitesonstovetop.Why?Heatissetathightemperature.

• Thesmokealarmalertsthepersontothere.Why?Thealarmisinworkingcondi-

tion and the person hears the alarm.

• Thepersonreturnstokitchenandrespondsinappropriatelybyremovingtheam-

ing pan from the stove and carrying it away. Why? The person does not know the

appropriate response to a stovetop fire, which is to turn off the heat and cover the

pan with a lid.

• Thepersonisburned.Why?Thepersondropstheamingpanathis/herfeetand

spills the burning food.

• Theredepartmentisnotied.Why?Thepersonishurtandrealizesthereis

now out of control.

1-23

Fire and injury prevention can be studied using a scientific approach. The process of develop-

ing a sequence of events and identifying the root cause shows how and why risk events are

understandable, predictable, and preventable.

Summary

A community risk analysis identifies fire and life safety problems and the demographic char-

acteristics of those at risk in a community. A risk analysis provides insight into the most

significant fire and life safety problems and the people who are affected by them. The results

create the foundation for developing risk reduction and community education programs.

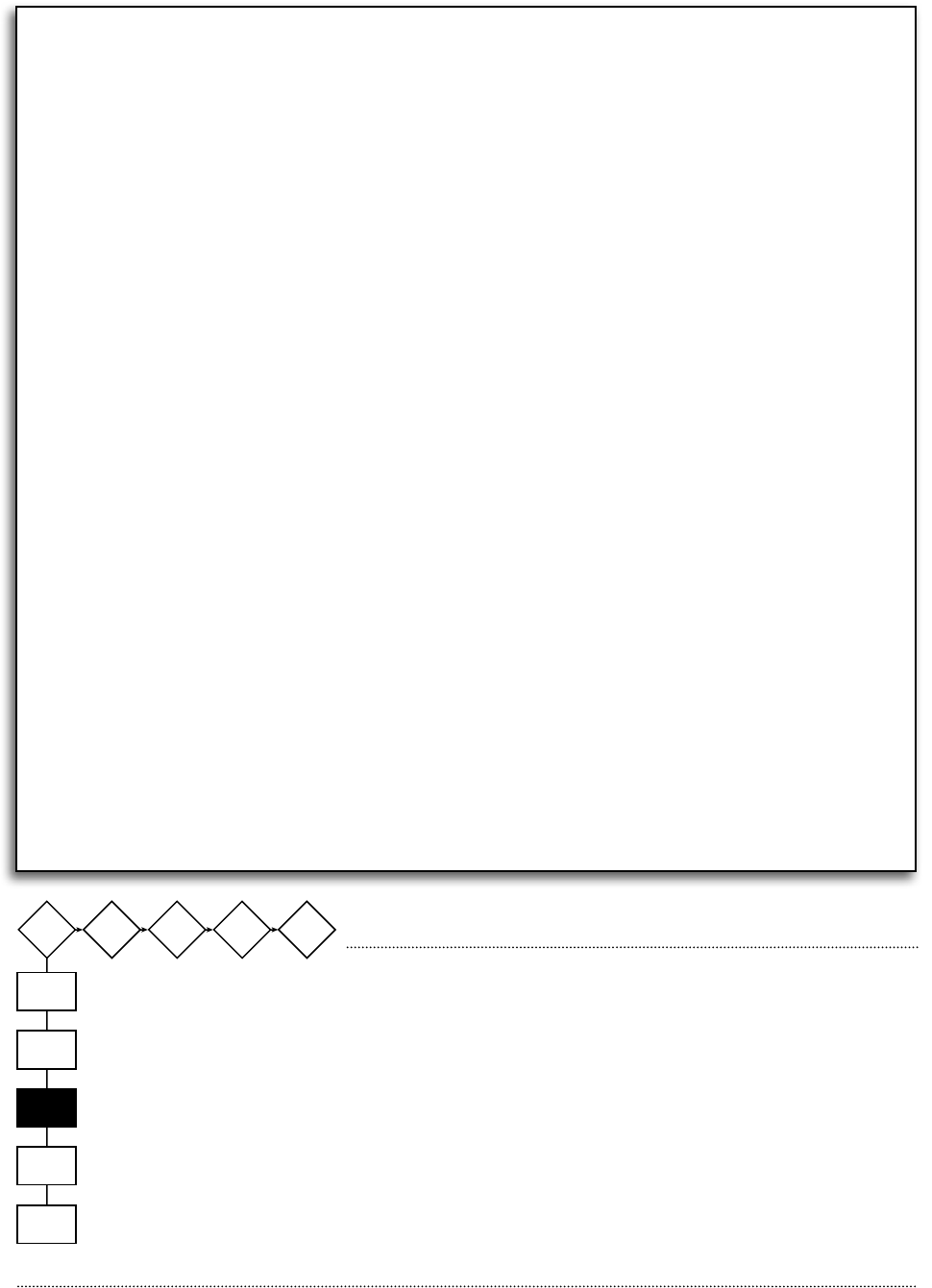

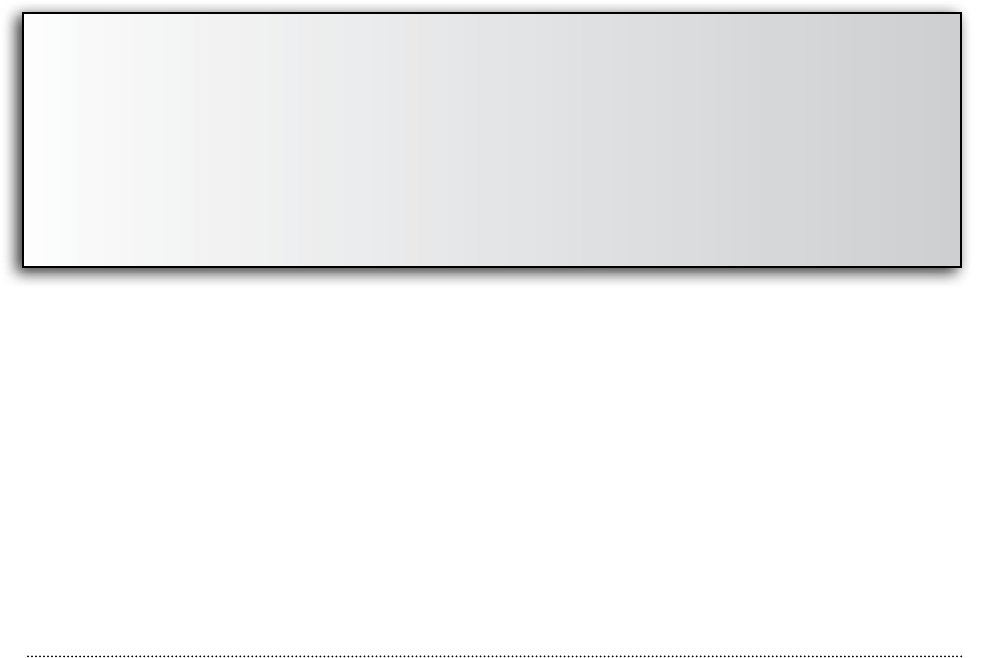

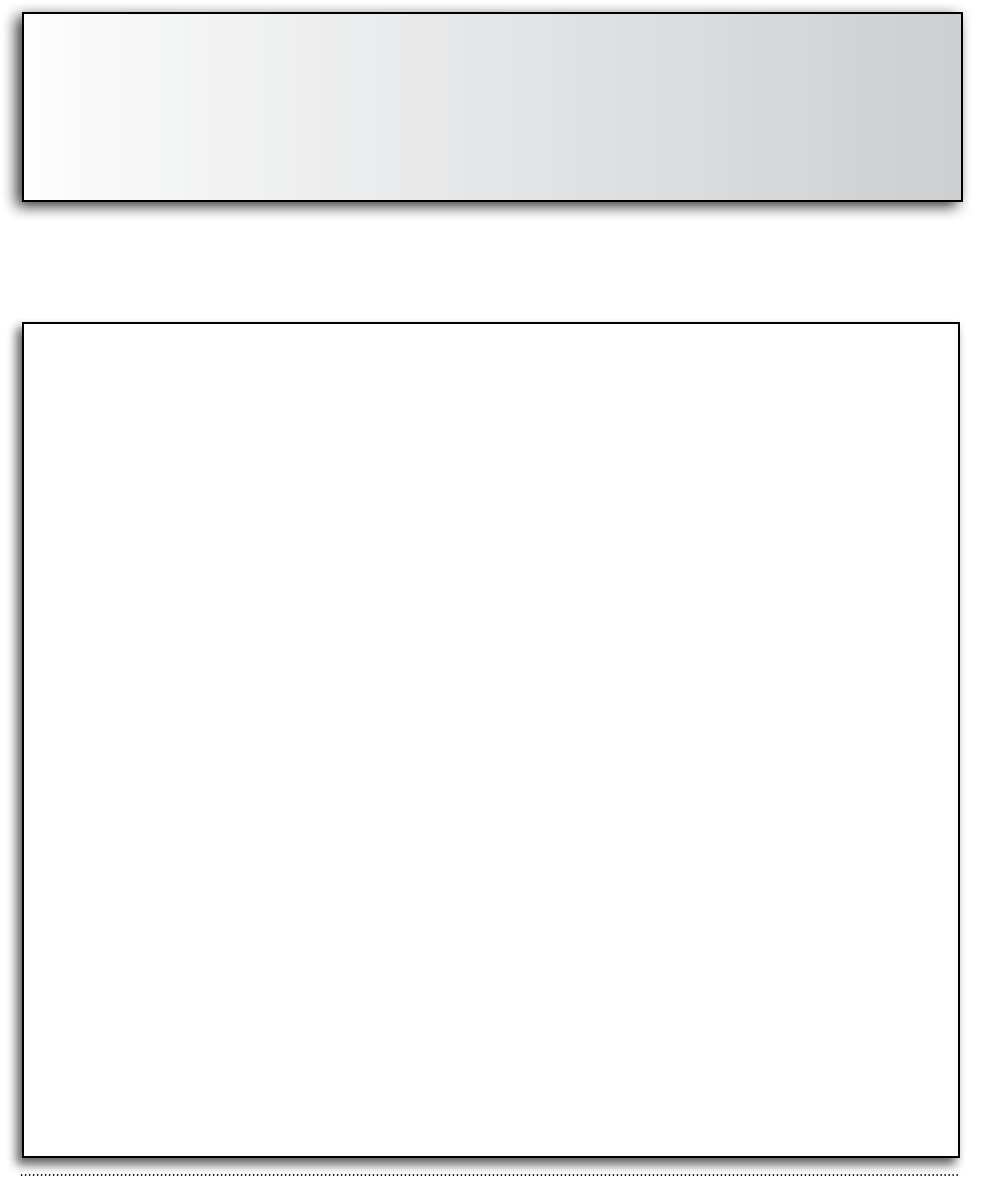

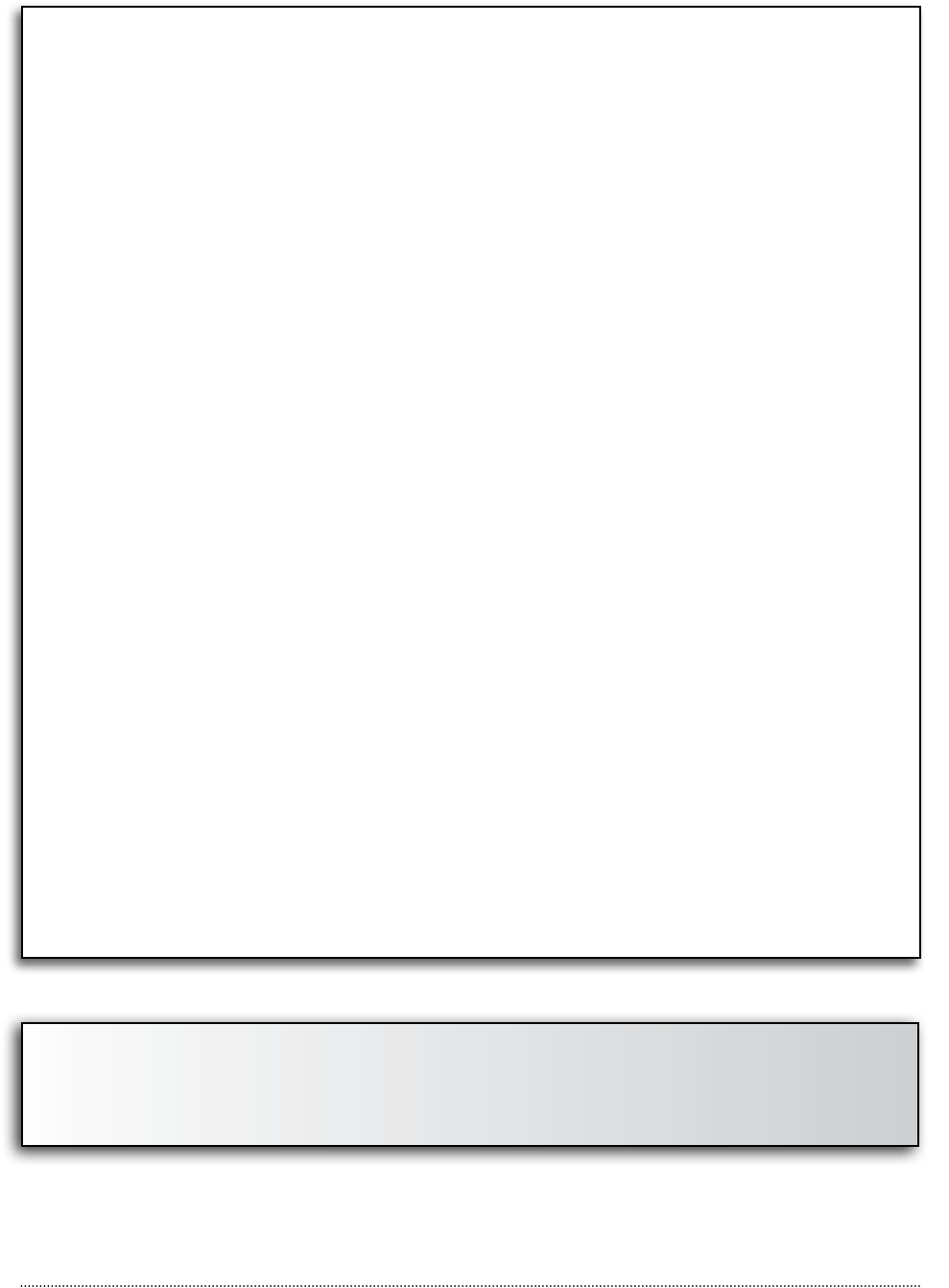

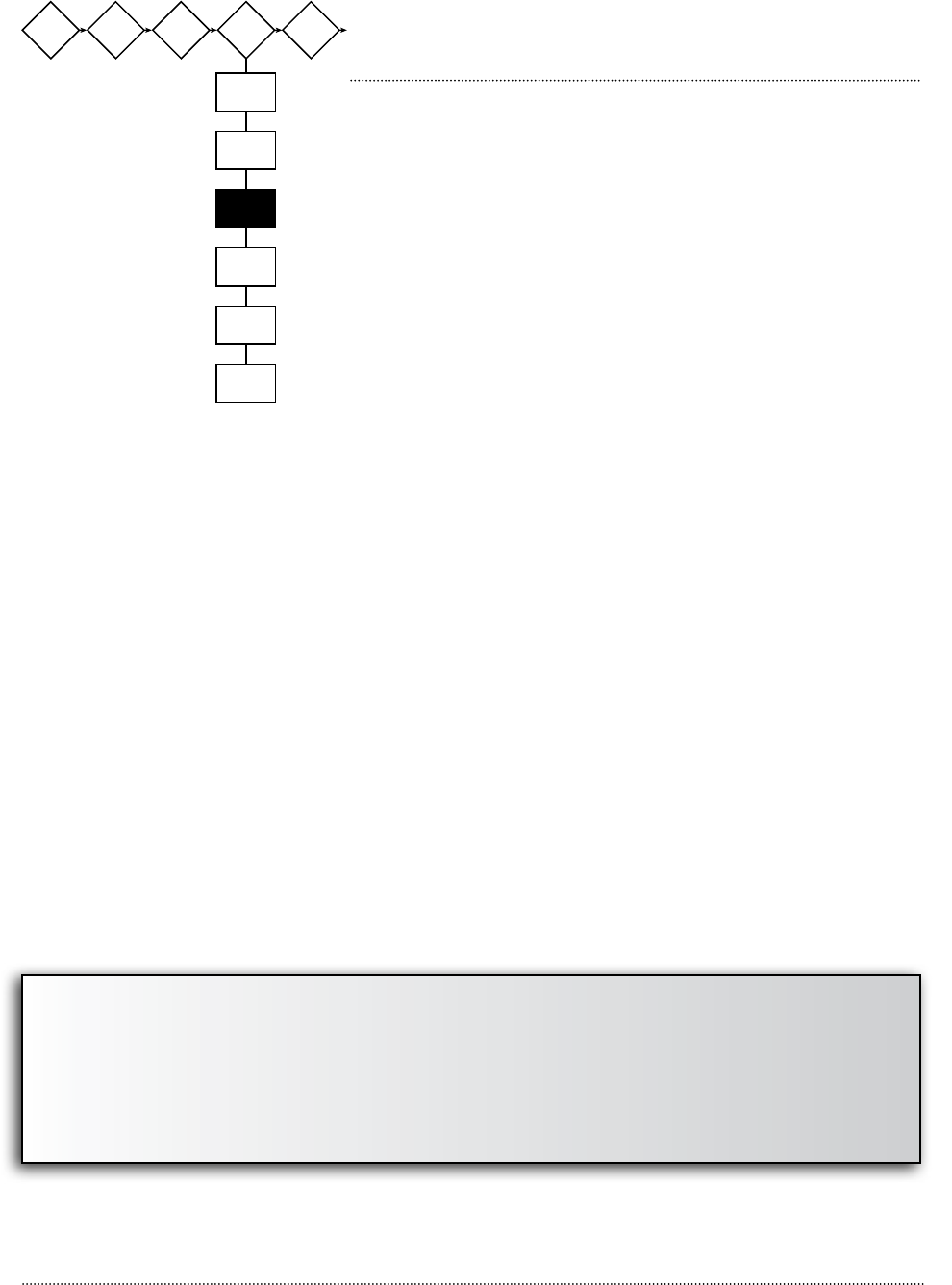

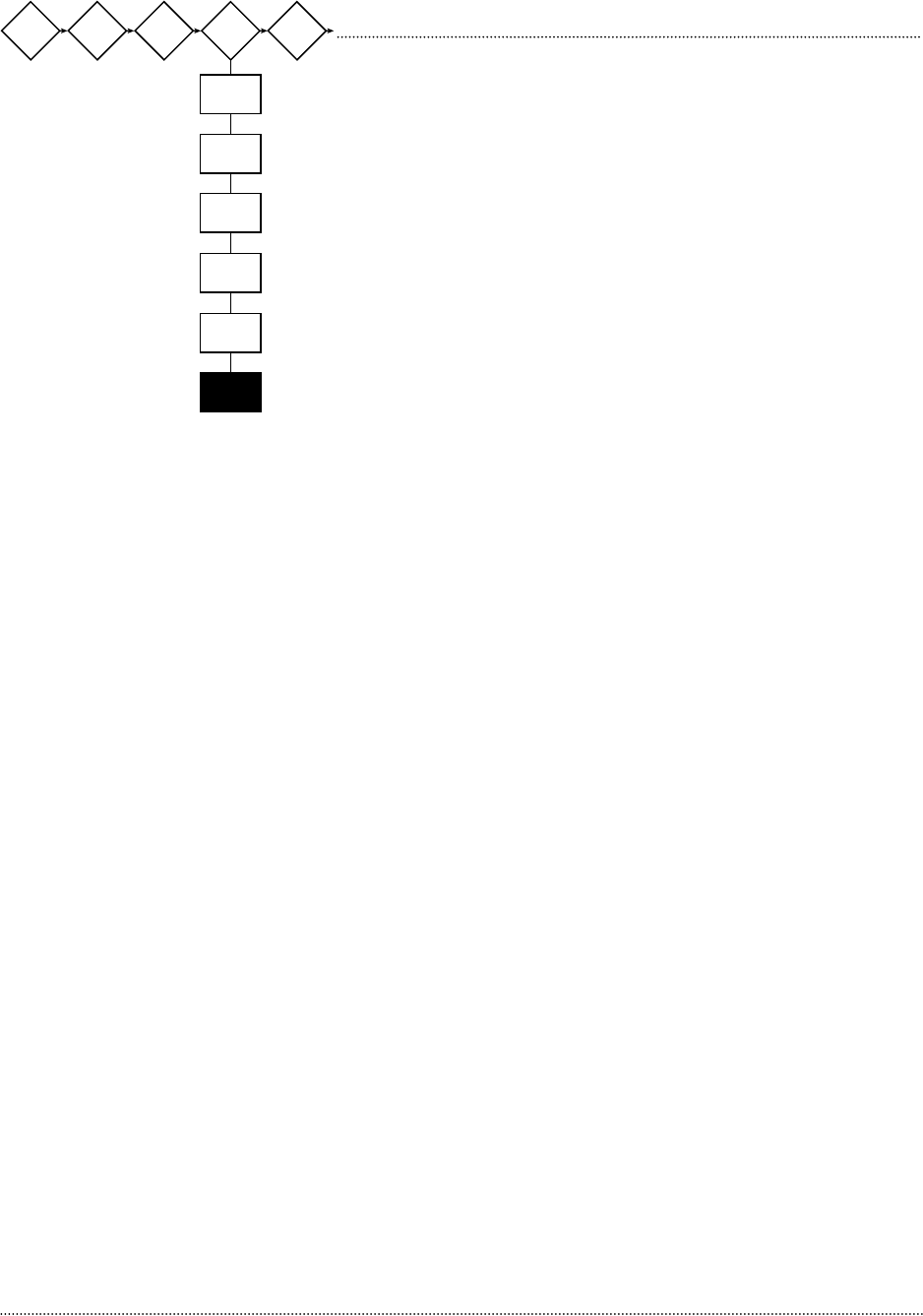

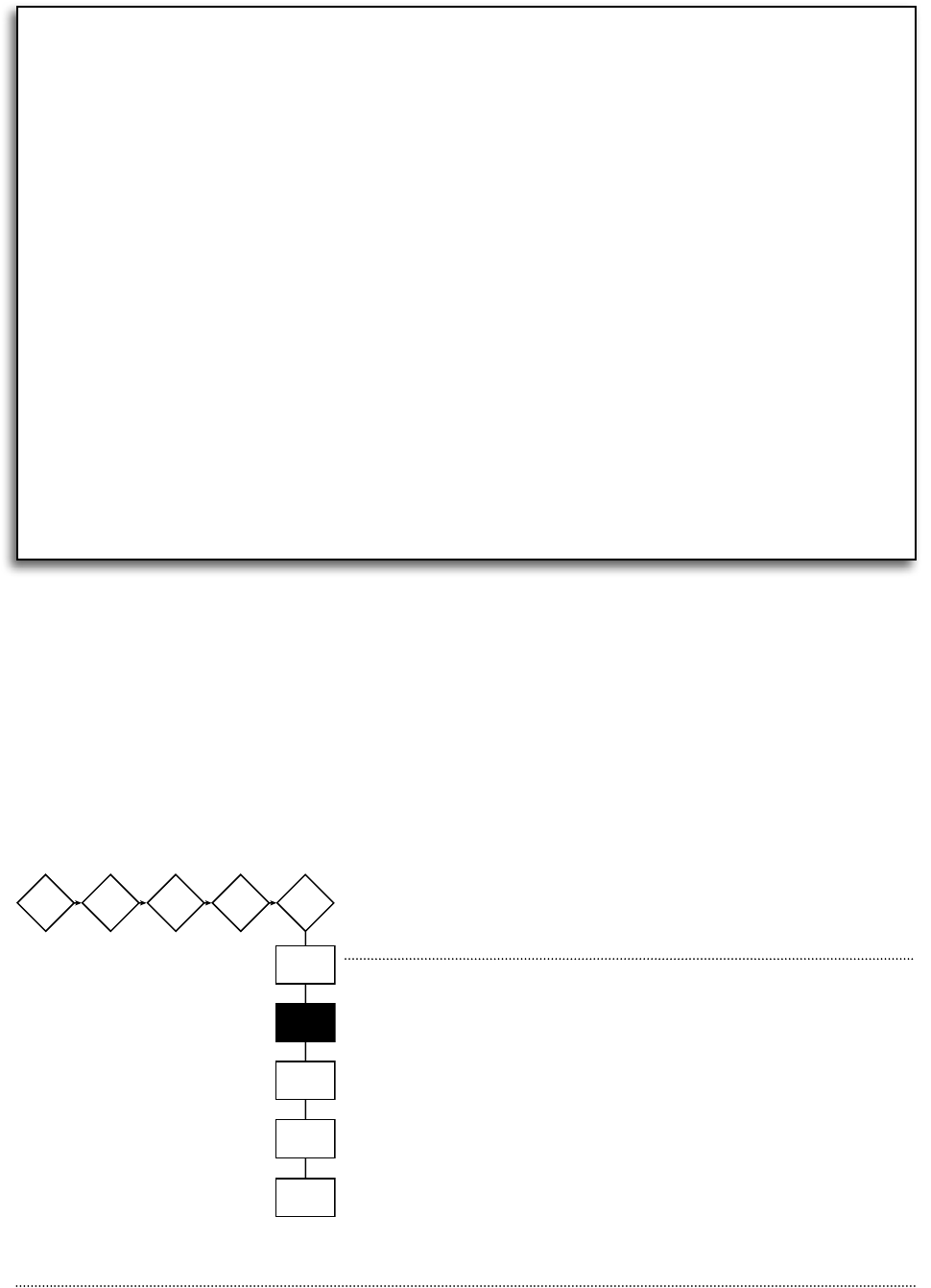

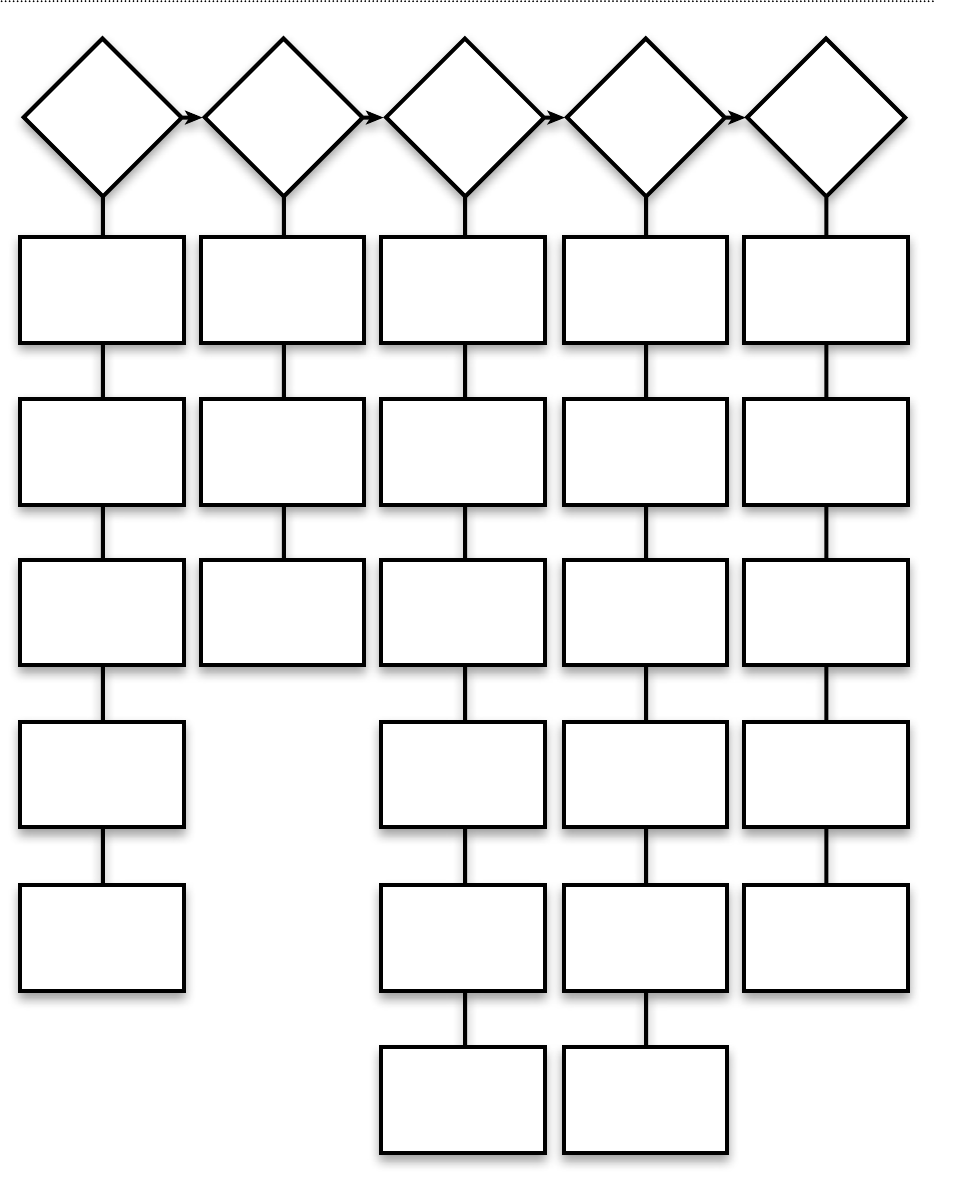

Conduct a

Community

Risk

Analysis

Develop

Community

Partnerships

Create an

Intervention

Strategy

Implement

the

Strategy

Evaluate

the

Results

Identify

Possible

Partners

Interpret

Community Risks

and Problems

Form a

Community

Planning Team

Step 2: Develop Community Partnerships

Chapter 2

Step 2: Develop Community Partnerships

Introduction

There are many reasons for developing community partnerships. The main reason should be

obvious. Consider this example: There is a major forest fire in a remote area. A single fire

department is sent to fight it with one engine unit and one firefighter. No matter how much

effort is expended, the fire is just too big to be affected in any significant way without addi-

tional help. The same is true when attacking a significant community fire or injury risk. One

person or organization will find it impossible to make a positive change without assistance.

Just like fire suppression, public education aimed at reducing community fire and injury risk

is serious business. When suppressing fires, most departments rely on mutual aid from other

organizations. The same strategy should be applied to community risk reduction programs.

Having one or more partners makes sense in terms of having more minds, bodies, and re-

sources to tackle the problem. Sharing the tasks of targeting the problem, developing a plan,

and implementing the solution is more productive in terms of creativity, credibility, and

overall effectiveness. The most successful risk reduction efforts are those that involve the

community in the planning and solution process.

What community resources are needed for risk reduction?

When the term “resources” is used, many people immediately think of money. It is true that

financial funding is needed to reduce most risks. However, money alone will not accomplish

anything. A broader spectrum of resources is required to conduct a successful risk reduction

effort. Examples of additional important resources include the following:

Knowledge: Knowledge of the problem and possible solutions, including a factual descrip-

tion of the community and its associated risks, is very important. Such knowledge is needed

for an accurate community risk analysis.

There are always many people and groups that will be able to offer insight into the communi-

ty, the people who live and work in the community, and the risks found in the community.

Think teamwork! As with reghting, and even baseball, community risk reduction

is best done by a group working together.

The work of a single organization aimed at reducing risk will cost a lot over the long

haul in terms of money, time, and effort spent, with little to show for all the effort.

2-1

It is up to the community educator to identify them and work with them to reduce the

risks.

In-kind support: This involves resources provided in lieu of money, including equipment,

printed materials, supplies, and personal effort. Donated professional services such as con-

sultations, program evaluations, and graphic design work are all examples of in-kind re-

sources.

Political support: Support for the risk reduction process from elected officials is very helpful

to finding success. The public educator should discuss any plans or ideas with elected officials

who have a stake in the program outcome. These people may know how additional resources

can be obtained, and often will have information important to program development.

Community support: Partnerships with people and organizations in the community can

identify risks, planning measures, and resources required to get the risk reduction process

started and the program implemented.

Emphasis is often placed on nances, but additional resources are equally important.

Identify Possible Partners

What is a community partner?

A community partner is a person, group, or organization willing to join

forces and address a community risk. It is important to identify a group of

partners who have a stake in the success of the risk reduction program.

How does the public educator nd help?

An easy way to start finding help is to just start networking and talking to people you know.

In addition, the use of the Internet and telephone directory is an easy way to start. A logical

first step is to find out which groups might be interested in a specific risk reduction effort or

already are addressing the selected risk issue. It is important to avoid duplication of effort.

Think about what part of the population needs to change in order to reduce the risk. Con-

sider which groups are already providing services to these people. Think about those in the

community who care about the risk issue and the people it is affecting.

These people may be the best ones to deliver the message. Another approach is to find out

who has the resources needed to address the problem.

2-2

Bottom line questions: Which people are the movers and shakers in the community who

will help get the effort started and the job done? Who can offer leadership, skills, credibility,

contacts, influence, and resources?

These are some possible community partners;

• groupsalreadyinterestedoraddressingthesameorasimilarriskissue;

• membersofthepopulationwhoareaffectedbytheriskissue;

• people/groups who feel thenancial impact of therisk issue(insurancecompanies,

property owners, American Red Cross disaster services);

• groupsalreadyprovidingservicestothepopulationaffectedbytheriskissue;

• communityserviceandadvocacygroups;and

• groupsthatcanhelpdelivermessages(media,clergy,schools,marketingorganizations).

2-3

Recruit a core group of primary stakeholders who will share the responsibilities of

developing and implementing a quality risk reduction effort.

Working alone may seem like a good idea; however, failure to obtain the perspec-

tive of, and creative input from, others will limit risk reduction efforts.

Interpret Community Risks

and Problems

Don’t expect everyone in the community to recognize instantly that a par-

ticular problem exists. Instead, expect them to be part of the solution pro-

cess by educating them about the problem. Use the community profile and

problem statement as the powerful tool that it is. This work provides a good

rationale for why others should consider partnering. Share the vision of the

plan and possible solutions with community leaders.

The most effective risk reduction efforts are those that involve the community in the planning

and solution process. The community needs to understand and agree that there is a problem

and that it can be solved. Sharing the information you have collected in a professional man-