FROM THE GROUND UP THE FOUNDING AND EARLY HISTORY OF THE FRANKLIN W. OLIN COLLEGE OF ENGINEERING

Table Of Contents

1 Preamble

3 Founding Inspiration: Franklin W. Olin

6 The F. W. Olin Foundation

10 The Big Idea

19 The-Less-Than-Once-in-a-Lifetime-Opportunity

27 Building the Plane As It’s Flying

31 Needham: America’s Newest College Town

34 What’s Next?

37 Afterword and Acknowledgments

38 Appendix A: Statement of Founding Precepts

41 Appendix B: Founding Faculty

42 Sources

45 Endnotes

Franklin W. Olin College of Engineering Olin Way Needham, Massachusetts www.olin.edu

From The Ground Up

The Founding and Early History of the Franklin W. Olin College of Engineering

A Bold Experiment in Engineering Education

This book has been printed on paper certified

by SmartWood to the Forest Stewardship

Council (FSC) standards, indicating the trees

are grown in responsibly managed forests.

The majority of the pulp is from eucalyptus

trees, which mature in six to eight years,

replenishing the forests quickly.

FROM THE GROUND UP THE FOUNDING AND EARLY HISTORY OF THE FRANKLIN W. OLIN COLLEGE OF ENGINEERING

Table Of Contents

1 Preamble

3 Founding Inspiration: Franklin W. Olin

6 The F. W. Olin Foundation

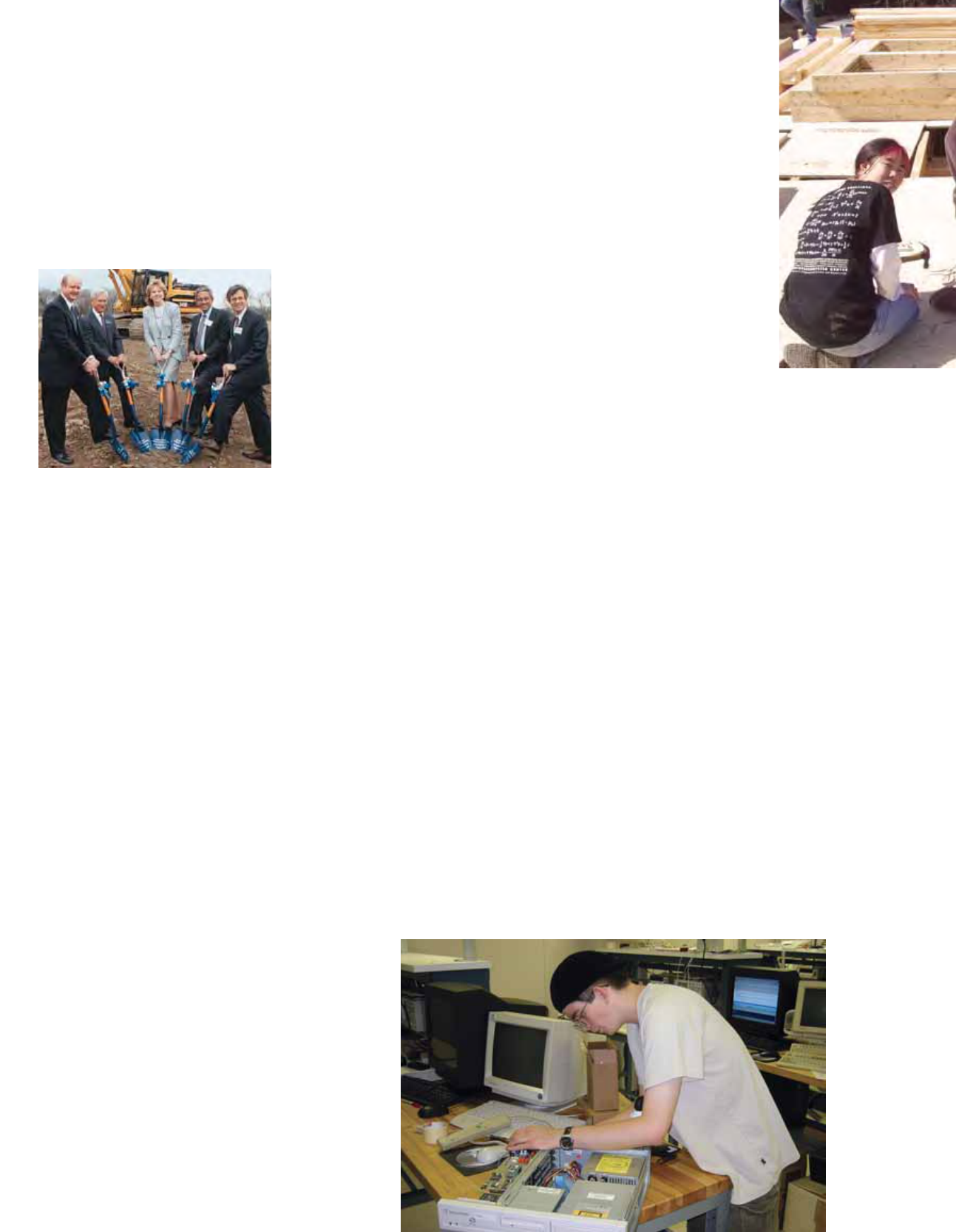

10 The Big Idea

19 The-Less-Than-Once-in-a-Lifetime-Opportunity

27 Building the Plane As It’s Flying

31 Needham: America’s Newest College Town

34 What’s Next?

37 Afterword and Acknowledgments

38 Appendix A: Statement of Founding Precepts

41 Appendix B: Founding Faculty

42 Sources

45 Endnotes

Franklin W. Olin College of Engineering Olin Way Needham, Massachusetts www.olin.edu

From The Ground Up

The Founding and Early History of the Franklin W. Olin College of Engineering

A Bold Experiment in Engineering Education

This book has been printed on paper certified

by SmartWood to the Forest Stewardship

Council (FSC) standards, indicating the trees

are grown in responsibly managed forests.

The majority of the pulp is from eucalyptus

trees, which mature in six to eight years,

replenishing the forests quickly.

From The Ground Up

The Founding and Early History of the

Franklin W. Olin College of Engineering

A Bold Experiment in Engineering Education

A Bold Experiment in Engineering Education

By Gloria Polizzotti Greis, Needham Historical Society

Credits

Text

Gloria Polizzotti Greis, Needham Historical Society

Photography

All photographs by Michael Maloney, unless otherwise noted.

Pages 1-10, photos courtesy F. W. Olin Foundation, unless otherwise noted.

Page 12, photos of William Schmidt and William Norden, courtesy F.W. Olin Foundation.

Pages 18 and 36, photos by Mark Flannery.

Page 21, poster image, and page 28, tabloid image, courtesy North Charles Street Design.

Design

Sylvia Peretz, Peretz Design

© 2009, Franklin W. Olin College of Engineering. All rights reserved.

In May 2006, the Franklin W. Olin College of

Engineering graduated its first class of seniors.

This was a milestone not only for the students, but

also for everyone associated with the institution. In

a very short period of time, this very talented group

turned a wooded hillside into a respected educational

institution whose reputation and influence continue

to grow.

The focus of this brief history is the genesis of the

idea to create a new kind of engineering college and

its realization as a living institution. Institutional

histories typically look back on past triumphs.

With little history (so far!), and with characteristic

momentum, any discussion of Olin will look to the

future more than it does the past. So this is just a

short respite, a quick stop on what promises to be

a long and adventurous journey.

June 2009

3

ranklin W. Olin’s life traced the arc of the

American legend. Born poor in rural Vermont

and largely self-educated, he retired as the head

of one of the country’s largest industrial corpora-

tions.

Olin was born in a lumber camp in rural

Woodford,Vt., in 1860. His father, Truman Olin,

was a master millwright who specialized in

building water wheels and other water-driven

machinery. As was common in those days, Olin

attended school until he was about 13, and then

went to work for his father. The family was then

living in Johnsonville, N.Y. (near Albany), where

Truman Olin was building the second-largest

water wheel in the world. At some point,

Franklin acquired a volume of the American

Machinist, replete with articles about the use

of steam to generate machine power. Since he

was already familiar with some aspects of power

generation, this was the inspiration that led him

to pursue an engineering education.

It took Olin the better part of five years to earn

both the knowledge and the money that a col-

lege education required. Secondary education

was scarce in rural communities. Instead, Olin

studied every book and article he could find that

would further his education, and even taught in

the local schools for a number of years to

increase his supply of books. Part of his time was

spent as a repairman, learning how machines

worked and how to fix them.

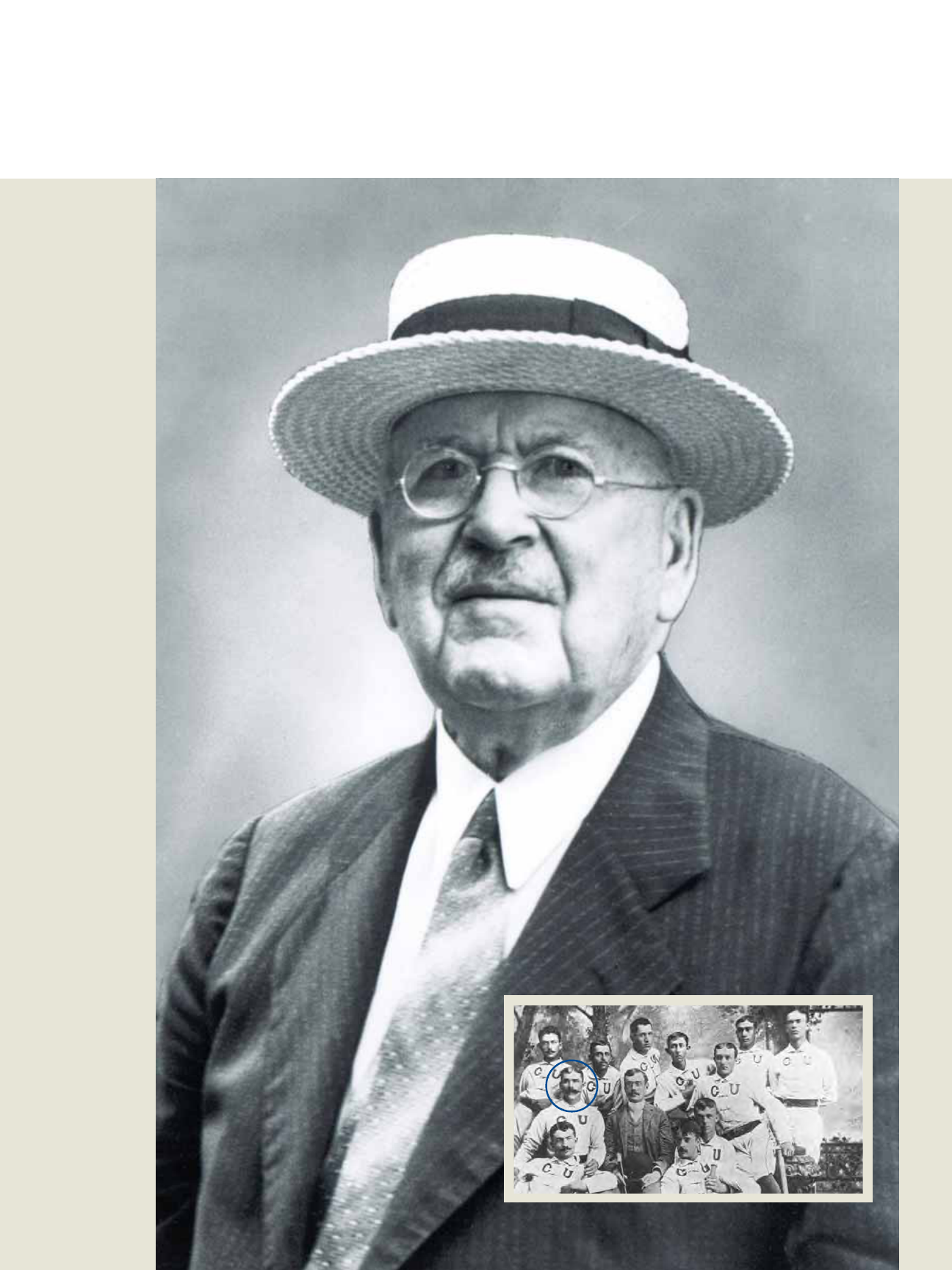

Olin was 22 years old when

he finally took the entrance

exam and was able to enroll

at Cornell University, where

he had two passions —

engineering and baseball.

Olin already had some experience playing local

ball before he reached Cornell. He was also older

and more muscular than most of his teammates,

and was made team captain in his freshman year.

His first challenge was to improve his team’s

lackluster hitting skills, which he accomplished

by introducing an indoor batting cage and

drilling his team relentlessly. The work paid off,

as the Cornell team became the Ivy League’s

most feared batters and consistent champions.

Olin also perfected the design of a concave bat

that gave him better contact, especially when hit-

ting curveballs. (See sidebar, “More on Olin’s Curved

Bat,” page 4.) This was legal in Olin’s day — the

size and shape of bats were not regulated, other

than the requirement that they have no more

than one flat side. His 540-foot home run, which

cleared the outfield and smashed into the foun

tain

Founding Inspiration: Franklin W. Olin

Franklin Olin died in 1951 at the age of 91. The scope of his

long career was a mirror of American industrial development in

the Machine Age. He began working in an era of water-powered

mechanics, and lived to see the advent of atomic power.

3

Franklin W. Olin;

Olin and his

Cornell University

teammates.

Photos courtesy

Cornell University

F

4

of Sage Chapel,

still stands as a

Cornell record —

an impressive

achievement, even

in these live-ball

days.

To earn money in

the summer, Olin

played professional

ball (also legal in

those days). He

was a left-handed

hitter and hit for

average rather than

power. Olin’s most

successful season in

the major leagues

was 1884, when

he played for the

Toledo Blue

Stockings and

the Washington

Nationals of

the American

Association, hit-

ting .312 in 48 games. His career average was

.316. Graduation in 1886 ended Olin’s baseball

career, though he remained a life-long fan.

Opportunities for civil engineers were rich in the

1880s, but it seems Olin was determined to work

for himself. He got his big break in the late

1880s when Olin Scott, a cousin, asked him to

take over supervision of the construction of a

new black-powder mill in New Jersey. Olin

would build several powder mills under con-

tract in the following few years. In 1889, Olin

married Mary Mott Moulton of Toledo, Ohio;

they eventually had three sons — Franklin Jr.,

Spencer and John.

By 1892, Olin had collected enough money and

experience to set up in business for himself. He

purchased a plot of land in the village of East

Alton, Ill., and using his own funds and invest-

ments from friends, he opened his first business,

the Equitable Powder Manufacturing Company.

This was a logical place to start; Olin had

acquired most of his professional experience in

the powder industry, and black powder was a

product whose market was strong and likely to

increase. It was the preferred industrial explosive,

especially in the rapidly growing coal mining

industry.

Equitable was the first of at least a dozen compa-

nies Olin would originate or acquire. Branching

out from powder production, Olin began to

develop plans for an ammunition plant and

opened the Western Cartridge Company in

1898. In succeeding years, he would enter

into all aspects of the ammunition business —

powder, shells, casings, lead shot and firearms.

Olin grew his businesses by having a focus on

quality and innovation.When a solution to a

particular problem was not available, he would

engineer his own. He designed and fabricated a

machine to load powder into shells that could

handle two shells at once, doubling the speed

of production and thus reducing cost. He also

improved shell primer production tenfold.

Olin played for the Toledo Blue

Stockings and other major

league teams during his summer

breaks from college.

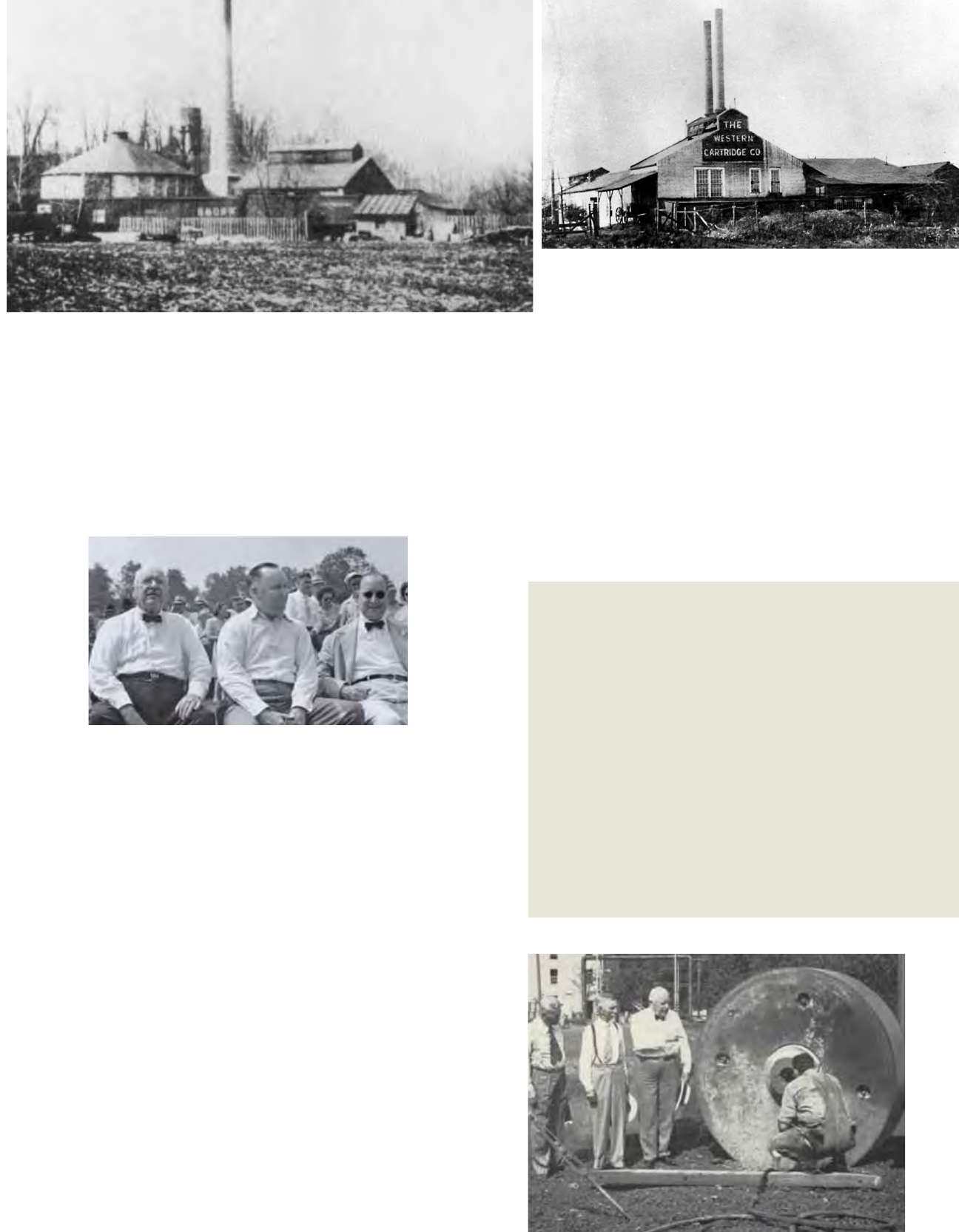

Olin’s first factory in East Alton, Ill., housed

the Equitable Powder Manufacturing

Company, founded in 1892.

Before he became a philanthropic

powerhouse, F. W. Olin was known for

his skills on the baseball field, where

his inventive side was in evidence: he

designed [Cornell] University’s first

batting cage — one of the first indoor

batting cages — and came up with a

unique curved baseball bat.

Carved from a wagon tongue, the bat

was similar to others then in use —

with one important difference. When

presented with a curve ball, the batter

turned the bat a quarter-turn to reveal a

distinct concavity. The bat is mentioned

several times in baseball literature and is

described by Morris Bishop in his History

of Cornell: “convex on one side for dis-

tance, concave on the other to meet the

drop curves.” Apparently Olin was having

a hard time hitting the curve, and he

theorized that a bent bat would com-

pensate for the motion of the ball. It’s

not documented if and when Olin used

it, but it would have been perfectly legal

in major league play.

— Excerpt of article, “Bent Out of Shape:

Where

Is Olin’s Curved Bat?” by Stephen

Eschenbach,

in Cornell Alumni Magazine.

Used with permission.

More on Olin’s

Curved Bat

5

The companies’ capacity for large-scale produc-

tion was rewarded by large military contracts

in both World Wars. Olin’s companies supplied

nearly seven billion loaded rounds during World

War I — enough when laid end to end to circle

the equator 18.5 times. In World War II, he

produced more than 15 billion rounds. By the

war’s end,

Olin’s

companies

employed

more than

62,000

people.

Franklin

Olin finally

retired in

1944, at the age of 84. The various Olin compa-

nies were consolidated into a single entity, Olin

Industries, and passed into the hands of his sons

John M. and Spencer T. Olin. Both had followed

their father to Cornell and then into engineer-

ing. Both had been employed in various divisions

of the company throughout their careers.

Franklin Olin died in 1951 at the age of 91.

The scope of his long career was a mirror of

American industrial development in the Machine

Age. He began working in an era of water-

powered mechanics, and lived to see the advent

of atomic power. He displayed the inventiveness

characteristic of a generation of engineers for

whom all solutions were designed from scratch

but displayed a business sense that valued effi-

ciency, innovation and practicality in these

solutions as much as he did effective design. In

this way, Olin embodied the characteristics that

would be enshrined in the Founding Precepts

of the college that now bears his name.

The original Western Cartridge Company building

in East Alton, Ill.

Photos courtesy Olin Corporation

Franklin W. Olin (left) and his sons Spencer and John.

For the war effort, Olin donated the original

grinding wheels from the Equitable Powder

factory to the U.S. government for scrap metal

in 1944.

Although Charles Horn was a longtime associate of Franklin

Olin, his son, former Olin College Trustee William Horn, never

had an opportunity to meet the man himself. He did occasion-

ally speak to him on the phone, however, when the old man

would call to speak to his father.

Horn was impressed that Olin always remembered his name —

a boy of eight or nine did not expect that kind of attention

from a man as important as Mr. Olin. Olin would also never

fail to ask how young William was doing in school. If he could

report that he was on the Honor Roll, Olin would send him a

quarter — a pretty decent tip in those days.

The 25-Cent Reward

6

ranklin Olin set up the Olin Foundation, Inc.,

in 1938, transferring a significant portion of

his personal wealth, including his majority share

of the Olin Industries stock and ownership of

Federal Cartridge Company of Minnesota, one

of his subsidiary companies:

“Franklin Olin had finally turned the presidency

[of Olin Industries] over to John... . Franklin got

the bulk of the stock, and the boys [John and

Spencer] split the rest. The old man then took his

marbles out of the game....He plunked his stock

into a charitable foundation.... If the boys did

not want control of the company to pass to the

foundation on his death, they’d jolly well have to

hustle up the money to buy back the shares.”

1

They did, leaving the foundation some $50 mil-

lion with which to play Santa. The foundation

was managed by James O.Wynn, a New York

tax attorney who had helped Olin set up the

foundation; Charles L. Horn of Minneapolis,

president of Federal Cartridge; and Ralph Clark

of Alton, Ill., Olin’s financial consultant.

Olin did not articulate a strict policy for govern-

ing the choice of grant recipients, and the giving

priorities of the foundation were determined

primarily by the personal interests of Olin and

his wife. Donations were generally smaller gifts

to hospitals, churches, schools and community

organizations. There were, however, two major

gifts made by Olin. The first, in 1940, was a

gift of nearly $1 million to build Olin Hall of

Chemical Engineering at Cornell University.

Cornell was the alma mater of Olin and all three

of his sons; the building was named in honor of

the eldest son, Franklin Jr., who had died as a

The F. W. Olin Foundation

1938

Franklin W. Olin forms

F. W. Olin Foundation.

1940

First major building

grant, to Cornell

University, Olin’s

alma mater.

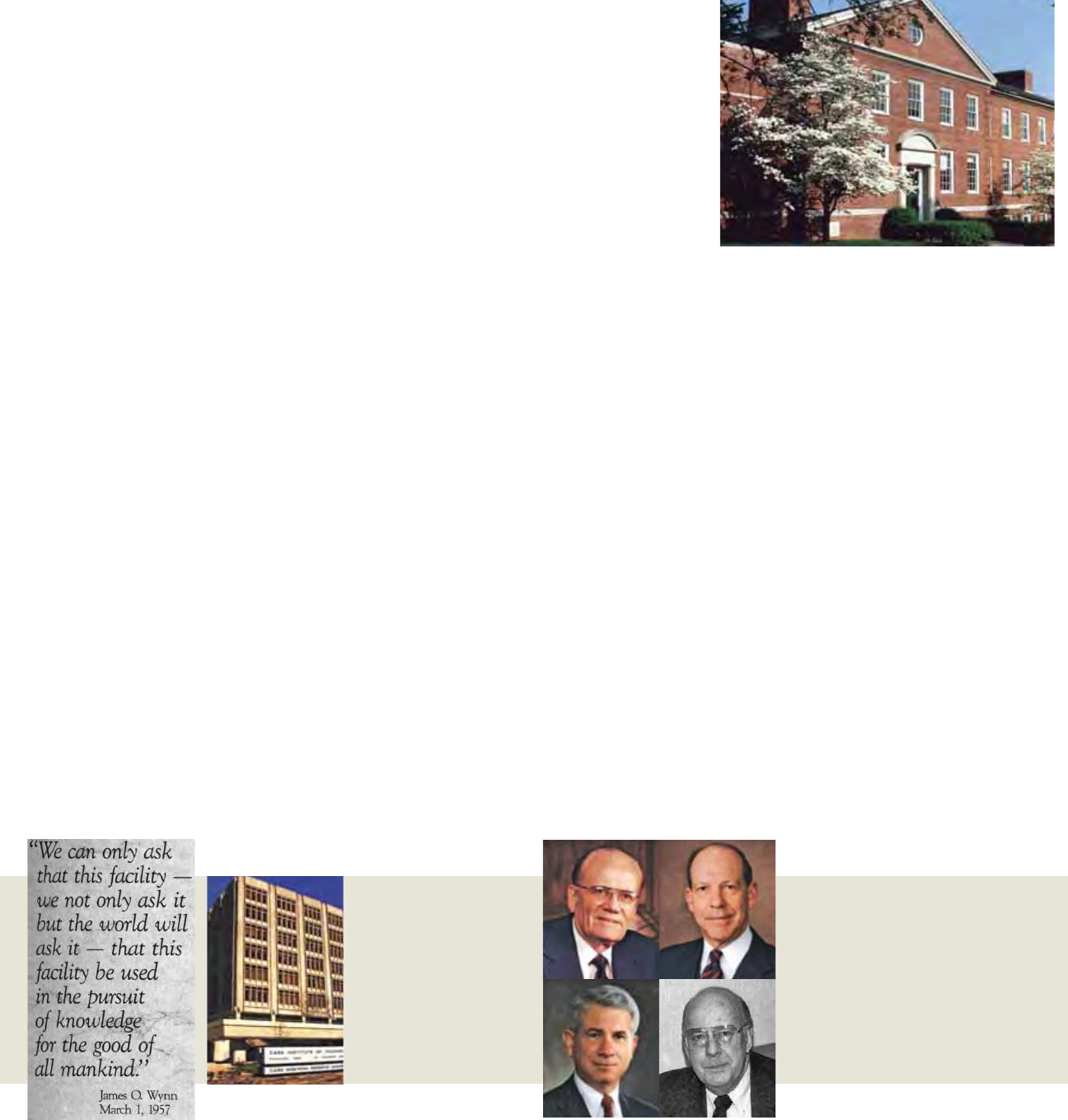

Directors James O. Wynn (joined the board in 1938),

Charles L. Horn (joined in 1946) and Ralph Clark

(joined in 1948), known as “the Three Musketeers,”

provided the foundation’s direction after Olin’s death.

F

7

young man. The second major gift was a grant in

1949 to build and equip a vocational high school

in Olin’s adopted hometown of Alton. In found-

ing the school, he stated in justification: “I don’t

want the youth of the present generation to

encounter the same difficulties in obtaining a

useful education that I had to overcome when

I was a boy.”

2

After Olin’s death in 1951, it fell to the three

directors — Wynn, Horn and Clark — to estab-

lish the future direction of the foundation. Olin

had left neither specific instructions nor a formal

statement of mission to clarify his long-term

intentions, so in going forward, the directors

chose to be guided by Olin’s two major gifts,

to Cornell and to the city of Alton.

The grant process evolved throughout the 1950s.

Grants were made to colleges and universities, as

well as to a variety of other causes — a clinic in

Florida named for Olin’s wife, Mary; a school for

children with cerebral palsy in New Jersey; and

a building for the American Farm School in

Salonica, Greece. There were two additional

grants for vocational schools, one in Atlanta, Ga.,

and one in Birmingham, Ala., which were

required by charter to remain racially integrated

and offer equal access to white and African-

American students:

“While the Directors of the Foundation were

certain that the southern states had made far

greater progress in the education of the Negro

than was generally believed, they felt that educa-

tion was not always [wise] in the sense that we

have waved the flag and said everyone can be

President of the United States and then handed

the Negro adolescent, ranging from brilliance

down to mediocrity, a high school diploma with

an economic opportunity equal in many cases to

zero. In Atlanta and Birmingham, we found local

industry surprisingly enthusiastic about the idea

of vocational training on the high school level for

Negro youth. The Foundation therefore built and

equipped in these cities vocational high schools

which by the terms of the contracts with the

Foundation will at all times be open to members

of the Negro race.”

3

By the late 1950s the parameters of the educa-

tional building grant program were clear. The

grant recipients were private colleges, which did

not have ready access to public funding and had

to rely on private fundraising to effect capital

1949

Second major gift,

to the town of

Alton, Ill., to build a

vocational school.

1951

Olin dies.

1950s

Grants made in

many locations:

Florida, New Jersey,

Greece, Georgia,

Alabama.

improvements. If a grant was made, the award

included sufficient funds not only to build the

building, but also to fully furnish and equip it so

that it would be ready for use on the day it

opened. The focus of these grants was for the

most part science and engineering buildings, but

8

other facilities (libraries, art and performance

centers) were also funded. Although large colleges

were numbered among the grant recipients, many

were small regional schools, generally chosen

because of some demonstrated excellence in their

particular niche. The choice of grant recipients

was also somewhat remarkable for the progressive

scope of the directors’ vision — grants to sectari-

an schools of all denominations and historically

minority colleges made up a significant propor-

tion of the gifts.

Because the grants were for the entire facility,

from the physical structure to the chairs and light

bulbs, individual grants were quite large, and

there were only two or three grants in most

years. This had two ramifications, and the first

was simply pragmatic. The directors ran the

foundation themselves rather than hiring a staff,

but their own time was limited — while Clark

was able to dedicate his time more or less fully

to the foundation,Wynn and Horn still had other

professional commitments. By managing the trust

themselves, they maintained tight control over

the priorities of the foundation and one of the

lowest cost-to-grant structures of any American

foundation.

The other advantage of a

large-grant program, apart

from its administrative efficiency, was the impact

that it could have. Grants on such a scale could

transform institutions by filling longstanding

needs, freeing up capital for additional expansion

and — most important — acting as a catalyst

to energize additional capital fundraising. For

smaller private colleges, especially those that his-

torically served a minority or sectarian commu-

nity and did not have a strong fundraising history,

an Olin grant validated the college’s mission,

gave luster to its reputation, and energized its

alumni and supporters. Olin grants were often

announced as the centerpiece of or kickoff to a

larger fundraising campaign.

This grant pattern was well-established by the

1960s. As college expansion accelerated in the

wake of Sputnik and the race to the moon, appli-

cations for foundation grants soared as well. The

Agenda of Applicants, the roster of grants under

consideration, grew to hold several hundred

requests. Given the rate of disbursement (two or

three per year) and the personal involvement of

the foundation directors in each grant, applica-

tions remained on the agenda for a long time.

Applicants could wait for years without

Early 1960s

Foundation solidifies

giving policies to focus

on building grants for

independent colleges

and universities.

1970s

New members added

to the board:

(clockwise from top left)

Carlton T. Helming, William

B. Horn, Robert D. Moss,

Lawrence W. Milas.

9

hearing anything about the progress of their

request, prompting one recipient to give to the

directors a plaque bearing the admonition: “No

News Does Not Mean No.”

By the mid-1970s, it was time for the Old Guard

to turn the foundation’s reins over to younger

hands. The original directors had managed the

foundation for more than 20 years; Charles Horn

was in his mid-80s, Ralph Clark was in his early

80s, and James Wynn was the young-

ster, in his late 70s. New members

were added to the board in 1974,

drawn as before from familiar Olin

sources — new directors Carlton

Helming, Robert Moss and William

Horn (Charles Horn’s son) were all

officers of Federal Cartridge, and

Lawrence Milas was the law partner

of James Wynn and legal advisor to

the foundation. A deliberate effort

was made in selecting these men to

maintain the continuity of the grant

program. In 1987, the foundation

formally changed its name from the

Olin Foundation to the F. W. Olin

Foundation, to be identified more

closely with its founder and clearly

distinguish it from other “Olin” foundations

established by his sons and others.

The new board maintained the grant program,

but streamlined the process for selection, ulti-

mately opting for a regular annual review and

notification cycle. Overall, from 1938 until 1997,

when the grant program was suspended, the

Olin Foundation funded the construction of 78

buildings at 58 different institutions.

Olin Foundation Building Grant Recipients

Augustana College

Albion College

Alfred University

Babson College

Bard College

Bates College

Birmingham-Southern College

Blackburn College

Bradley University

Bucknell University

Carleton College

Case Western Reserve University

Centre College

Clemson University

Colby College

Colgate University

Colorado College

Concordia College

Connecticut College

Cornell College

Cornell University

Denison University

DePauw University

Drake University

Drury College

Florida Institute of Technology

Franklin W. Olin College of Engineering

Gustavus Adolphus College

Hampton University

Harvey Mudd College

Jarvis Christian College

Johns Hopkins University

Kenyon College

Lafayette College

Lewis & Clark College

Luther College

Macalester College

Marquette University

Millsaps College

Mills College

Nebraska Wesleyan University

Roanoke College

Rollins College

Rose-Hulman Institute of Technology

Southwestern University

Tufts University

Union College

University of Denver

University of San Diego

University of Southern California

Ursinus College

Vanderbilt University

Wake Forest University

Washington & Jefferson College

Whitman College

Willamette University

Wofford College

Worcester Polytechnic Institute

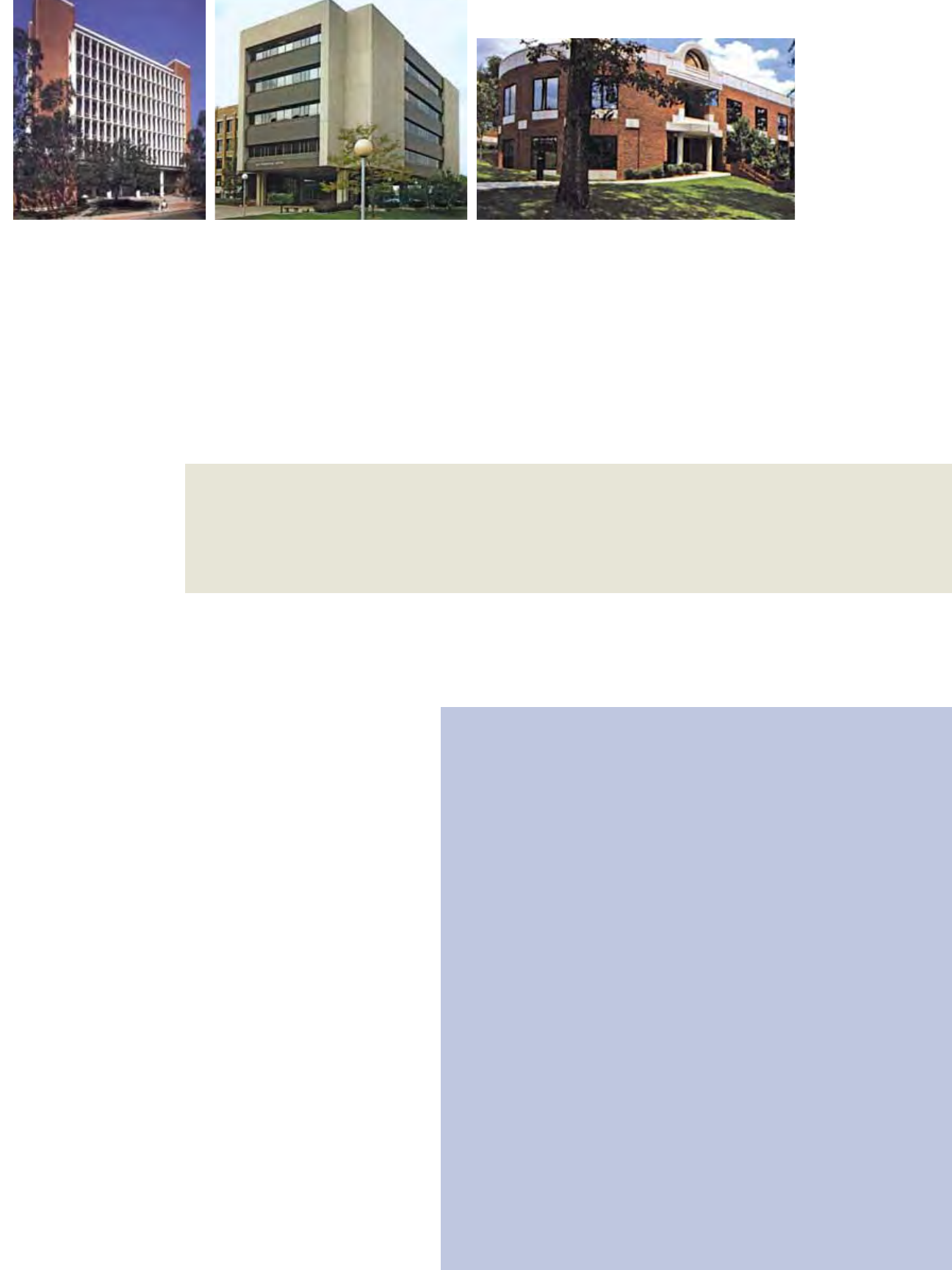

Worcester Polytechnic Institute (1957), University of Southern California (1964), Marquette University (1975) and

Birmingham-Southern College (1984) buildings.

Large Grants could transform institutions by filling longstanding needs,

freeing up capital for additional expansion and — most important — acting as

a catalyst to energize additional capital fundraising.

10

The Big Idea

here was another board transition in the

1980s. Helming and Moss passed away;

William Norden, a lawyer in Wynn and Milas’

firm, took over as legal counsel and joined the

board, as did William Schmidt, another former

officer of Federal Cartridge. For the first time,

there was no board member who had a personal

acquaintance with Franklin Olin. The closest

connection was William Horn, whose father,

Charles, had known Olin but who was not him-

self a colleague of the old man.

As governance of the foundation moved further

and further from the founding directors, the

problem of long-term planning and succession

began to loom. In the 30 years since Olin’s death,

the foundation had worked without a formal

written mandate, following a path determined

by the directors’ personal knowledge of Olin’s

intentions and their own expertise. The founda-

tion itself was run with a minimal staff and

maintained one of the lowest cost-to-grant ratios

of any foundation in the country. The directors

themselves evaluated the applications and con-

ducted the site visits. This thriftiness allowed

them to keep more money in the grant pool

and maximize the impact of each grant on the

recipient institution.

Nevertheless, as it looked forward to the next

30 or more years, the board could not expect to

continue in the same manner. All previous direc-

tors had come to the board because of their

professional services to the foundation or with

Federal Cartridge Company, an Olin subsidiary

that was owned by the foundation. However,

changes in federal tax laws required the founda-

tion to sell Federal Cartridge. Ownership of

Federal had been transferred to the foundation

when Olin first established it in 1938; it was the

foundation’s largest asset, and over the years its

profits had provided significant funds to support

the building grants program. The sale of Federal

Cartridge guaranteed

that future directors

would have to come

from outside the circle

of professional and

corporate affiliations

that had surrounded

Mr. Olin. The board’s

greatest concern was

that new directors,

with no connection to

the founding culture

that had guided the

foundation since its

Foundation Directors: William Norden, William Schmidt,

Lawrence Milas, William Horn.

In order to continue as

they thought appropri-

ate, the board would

have to come up with a

succession plan and

restrictions that would

limit future directors’

discretion and maintain

the foundation’s focus

on college buildings.

The other option was to

dissolve the foundation

and spend down its

resources.

T

11

inception, could take the foundation in a new

direction. To that point, the directors had care-

fully guarded a mission that they thought best

reflected the intentions of Franklin Olin.

By the early 1990s, the problem of strategic plan-

ning for the future became acute, and the board

was faced with the decision whether to continue

or dissolve. In order to continue as they thought

appropriate, the board would have to come up

with a succession plan and restrictions that would

limit future directors’ discretion and maintain

the foundation’s focus on college buildings. The

other option was to dissolve the foundation and

spend down its resources, either by choosing two

or three very large projects or by dividing the

money among the 50 or so Olin grant colleges

to finance building upgrades or new construc-

tion. Such a project, however, would take years

and require a large staff to administer.

The task fell to Milas, who had been president

of the foundation since 1983, to lead the effort

to consider the advantages and disadvantages of

the various options and make a recommendation

to the board. If there is one person who can be

called the founder of Olin College, it is Milas.

His advocacy of the idea of establishing the

college and his involvement in its development

are the reasons the college exists today.

However, as Milas initially sat down to review

his options, the way forward for the foundation

was not at all clear. The solution had to not only

be one that advanced the foundation’s purpose to

best advantage, but one that also would create the

greatest possible impact for its resources. In keep-

ing with long-standing Olin Foundation priori-

ties, the solution should focus on education and

engineering. Milas was considering collaborations

with various types of institutions; each possibility

had its strengths and weaknesses, but none really

fit what he was trying to accomplish. It was

Milas’ wife, Marjorie, who finally provided the

inspiration. After putting up with her husband’s

mumbling and pacing around the house, she

finally observed, in jest: “Why don’t you just start

your own damn college?” Milas’ first thought

was,“You’d

have to be

crazy.”

4

On second

thought…as

a solution to

the problem, it

covered all the bases — and it certainly had

impact. Milas thought it over carefully and

worked on it for several months before bringing

the idea to the board in the fall of 1993.

It is probably safe to say that Milas’ report took

the directors by surprise. Entirely bypassing

succession plans and the distribution of building

funds, Milas proposed three bold new scenarios:

give the entire sum to a smaller but well-regarded

engineering school and use the money to raise it

to the top tier; use the money to start an engi-

neering school at a well-regarded institution that

did not have one; or the most costly and daring

option, start a whole new school from the

ground up.

The board’s reaction was decidedly mixed. The

proposals, especially the latter, would give the

foundation a great deal of publicity and make a

huge impact on engineering education. But it

was also a complex and uncertain undertaking

that could result in nothing more than a well-

publicized failure that compromised the founda-

tion’s reputation as well as its assets. Nevertheless,

the board gave Milas the approval to explore it

further.

“Why don’t you just start

your own damn college?”

— Marjorie Milas

12

To make matters more complicated, as the

directors deliberated the future of the Olin

Foundation, engineering careers in America were

at a low point. The Cold War was, if nothing else,

a boon to American engineering; government

funding and Defense Department contracts had

fueled huge advances in technology for over 40

years. Shifts in funding after the collapse of the

Soviet Union led to a soft employment market

for engineers and a drop in the demand for

engineering degrees. In response, the National

Science Foundation (NSF) and American busi-

nesses took aim at this same issue — looking to

retool engineering education in the same way

that the engineering profession was trying to

retool itself. In the view of the NSF, engineering

education had become too specialized, leading to

engineers with excellent technical skills but none

of the other skills that they needed to succeed in

the new, more business-oriented environment

that was taking shape. Many engineers’ careers

would stagnate after a few years, because they did

not have the communication or teamwork skills

the needed to advance as managers and their

expertise was too narrow for them to effectively

communicate within the company or with

clients or partners. In the words of Marshall Lih,

director of the NSF’s Division of Engineering

Education, most schools were educating engi-

neers to be bricklayers rather than cathedral

builders.

5

Engineers needed teamwork and com-

munication skills, especially for teams that includ-

ed non-engineering specialists. As businesses

became more global in their focus, it would be

necessary for engineers, like other professionals,

to communicate effectively across cultural lines.

To succeed in this new environment, they would

also need to be creative, think like entrepreneurs

and possess excellent design skills.

The requirements of business and the changes

championed by the NSF were adopted by

the Accreditation Board for Engineering and

Technology (ABET) in its “Criteria 2000,” a

revised rubric for the accreditation of engineer-

ing education institutions. According to these

criteria, engineers of the future should possess:

• the ability to apply knowledge of math,

science and engineering

• the ability to design and conduct experi-

ments, and analyze and interpret data

• the ability to design a system, component

or process to meet a desired need

• the ability to function on multidisciplinary

teams

• the ability to identify, formulate and solve

engineering problems

1980s

William Schmidt and

William Norden join

board as directors.

Federal Cartridge

Company sold.

1993

Milas proposes

new college

idea to the

board.

Late 1990s

ABET adopts Criteria 2000

guidelines for accreditation

of engineering education

institutions.

13

• an understanding of ethical and professional

responsibility

• the ability to communicate effectively

• the broad education to understand the

impact of engineering solutions in a global

and societal context

• a recognition of the need for, and the ability

to engage in, lifelong learning

• a knowledge of contemporary issues

• the ability to use the techniques, skills and

modern engineering tools necessary for

engineering practice

More than half of these 11 criteria addressed

nontechnical requirements that were typically

outside the scope of an engineer’s training.

6

Given the decline in the demand for engineering

degrees, why did the Olin Foundation think that

the country needed another engineering school?

Milas’ response — echoed by ABET, the NSF

and American business — was that the country

did not need another engineering school, it

needed a different one. Although some engineer-

ing schools were seeking to implement changes

in the way their students were taught, many did

not see the need for such change. By the NSF’s

estimates, more than 50 percent of engineering

students dropped out of the program by their

sophomore year, and the demand for engineering

degrees had declined by 20 percent since 1985,

despite the strong and technologically-focused

economy. Nevertheless, less than 25

percent of the faculties of the nation’s 300 engi-

neering institutions saw a need to overhaul their

curricula.

7

Established schools had entrenched

institutional cultures, interdepartmental competi-

tion for resources and funding, a defined faculty

structure, and established research and funding

relationships that could not simply be jettisoned.

Progress, when it came, could only be slow and

incremental.

The Olin Foundation directors debated their

options in the light of what they had learned in

their consultations with educators, businesses and

organizations like the NSF and ABET. Their

many years of reviewing grant applications and

meeting with more than 100 college representa-

tives annually had given the directors a strong

and thorough understanding of the strengths and

weaknesses of America’s higher education system.

Making over an existing school or endowing a

new school at an established institution had

similar limitations, and the potential to effect real

change in the way engineers were trained was

minimal. After several years of deliberation, the

foundation’s directors eventually decided that

their best option was to start a new school,

which could be a laboratory to test this new

1997

Olin Foundation receives charter

from Massachusetts Board of Higher

Education to establish Franklin W.

Olin College of Engineering.

2002

Foundation and Olin College adopt

a Statement of Founding Precepts.

Arrival of first freshman class,

which includes 30 Olin “partners”

who joined the college the year

before.

14

direction in engineering education unencum-

bered by the baggage of the past. Olin’s college

could be nimble, without an established faculty

or institutional culture, no territories to jealously

guard, no competing priorities, no burdens of

tradition. It could be set up from scratch with the

single focus of engineering excellence, with an

administration and faculty dedicated to perfecting

an engineering curriculum. By eliminating both

academic departments and faculty tenure, the

college could more easily craft an interdiscipli-

nary curriculum that could respond quickly to

changes in the engineering field.

The foundation chartered its college in 1997,

beginning the process that would eventually

dissolve the charitable institution in favor of the

new college. To ensure that the founder’s legacy

would be preserved and to distinguish this effort

from the endeavors of the other foundations that

bore the Olin name, the school was to be called

“the Franklin W. Olin College of Engineering.”

In October 1997, the foundation petitioned the

Massachusetts Board of Higher Education for

permission to organize the college and award

Bachelor of Science degrees in engineering, as

well as honorary doctorates in engineering, laws

and humane letters. The board’s approval was the

necessary first step in obtaining a charter from

the state. The process was not expected to be

easy, since much of the required documentation,

especially the curriculum plan, had yet to be

written. This could also be a

very slow process, often last-

ing as long as two years, but

none of the other plans could

go forward until the decision

had been rendered.

For an outline of the pro-

posed education program,

Milas sought the advice of

Dr. James Eifert, of Rose-Hulman Institute of

Technology in Indiana, then vice president for

academic affairs and later the founder of the

entrepreneurial Rose-Hulman Ventures program.

Rose-Hulman’s programs in engineering and

entrepreneurship were models for the type of

progressive and innovative education that the

Olin trustees wanted to offer. Eifert drafted a

curriculum outline that emphasized the impor-

tance of introducing opportunities for professional

practice alongside classroom training and allowed

considerable latitude for students to incorporate

personal interests and career goals into their

training.

In presenting their petition, the trustees outlined

an expansive vision of the role of engineering

training in professional and civic life, a vision that

was the first comprehensive statement of what

the new college would be. Olin-trained engi-

neers would be adequately prepared to build

anything and everything, from widgets to global

communities.

In the words of

Marshall Lih, director

of the NSF’s Division of

Engineering Education,

most schools were edu-

cating engineers to be

bricklayers rather than

cathedral builders.

15

The logistical portions of the petition outlined

Eifert’s plan for a curriculum of coursework in

mathematics, the sciences and engineering struc-

tured around a framework of professional men-

toring (including opportunities for professional

practice), experiential learning, and international

education and work experience. The curriculum

would be “vertically integrated,” allowing less-

experienced students to share projects with both

upperclassmen and faculty, as a means of engag-

ing their problem-solving capabilities and chal-

lenging their skills. For this to work well, the

college would have to attract the brightest and

most motivated students, and therefore the

trustees were eager to keep the financial and

institutional barriers as low as possible — tuition

for all students would be covered by a full schol-

arship, state-of-the-art equipment and resources

would be supplied, and the faculty-to-student

ratio would be low.

In order to keep the process on track, Milas

met with James Carlin, chairman of the

Massachusetts Board of Higher Education,

about the application. Carlin was intrigued by

the innovative nature of the Olin Foundation’s

proposal and encouraged the board’s staff to

expedite its review. Following a positive review,

the Board of Higher Education responded with

“speed, support and enthusiasm”

9

to Olin’s peti-

tion, approving the Articles of Organization and

the authority to award degrees within a few

weeks of their submission.

Following the approval of the articles came the

still harder work of crafting the college. The

powerful vision and program outlined in the

“We envision a 21st Century in which the industrial and commercial community is truly a global

marketplace....We believe that modern engineering education provides the optimum basic

preparation for the leaders of the future we see. We believe that engineers will continue to be

expected to practice their profession in the traditional technical capacities. In addition, however,

we believe that engineers will be called upon and must assert their leadership as managers of

technology-based commercial ventures and governmental agencies, as senior corporate leaders,

entrepreneurs, political leaders, and as specialized professionals in the fields of medicine and

law. We believe that engineers will be so important in this future society because their education

uniquely provides them with the essential knowledge, skills, processes and perspectives to

understand the complex system that modern life has become. Many educational programs

provide graduates with either the ‘know how,’ the ‘know why’ or the ‘know when.’ The Franklin W.

Olin College will enable its graduates to develop within themselves the necessary synthesis

of these three ingredients to emerge as the effective leaders needed to chart our course through

the future.

In short, we see a future in which an undergraduate engineering education becomes the true

‘Liberal Education,’ i.e. an education which liberates one to lead a personal and professional life

of full citizenship in one’s local, national and global communities.”

8

“Let it be said that the Foundation does not seek to establish a generic undergraduate engineer-

ing college — one that will simply offer programs similar to many others around the country.

Olin College is intended to be different — not for the mere sake of being different, but to be an

important and constant contributor to the advancement of engineering education in America

and throughout the world and, through its graduates, to do good for humankind.”

The precepts enshrined innovation in practice and pedagogy at the core of the college’s mission:

“Even a new institution can, with the passage of time, become resistant to change. If this were

to happen at the College it would be a tragic loss of opportunity for engineering education,

generally, and a terrible disappointment to the Foundation. The need for the College to be

continually open to change and to encourage and support a culture of innovation is paramount.

Risk-taking with respect to new programs or in the manner in which engineers are taught

should be routine. The College acknowledges that a culture of innovation is a fundamental

precept of the planning for Olin College.

The College commits itself to the need to

be open to change and to support a culture

of innovation and constant improvement

in every aspect of its operations and pro-

grams.”

16

charter documents became the starting point for

the school’s organizational structure. As the

trustees began to hire an administrative staff —

a president and deans — to implement this

vision, it became obvious that it would be

necessary to articulate a legal framework for the

commitment of the foundation’s assets to its new

college, and a contract that bound the staff to

pursue the foundation’s vision and expectations.

In the first few years, while they were occupied

with building the college, the trustees and

administration operated from a common set of

assumptions based on the founding vision articu-

lated in the charter and other documents.

Finally, in 2002, the foundation and the college

formally adopted a Statement of Founding

Precepts. The precepts codified the assumptions

and principles that inspired the founding of

the college and spelled out the foundation’s

philosophy of independence, innovation and

philanthropy:

17

The changes in engineering deemed necessary by

ABET and the NSF were acknowledged as the

framework for curriculum development:

• interdisciplinary and integrated teaching

• hands-on learning and research

opportunities

• improved communication skills

• students working in teams, similar to

industry practice

• exposure to other cultures or international

experiences

• a better understanding of business and

management practices

Most important, the Founding Precepts defined

Olin as “student-centered,” placing commitment

to the teaching of students, rather than the needs

of faculty, at the center of its endeavors. The

curriculum would address all aspects of students’

social and intellectual development, emphasizing

the arts and humanities as well as the sciences.

Furthermore, the foundation would promote

access for all qualified students by providing all

of them with full-tuition scholarships. Students

who choose to attend Olin College could do

so based on their evaluation of its educational

offerings, rather than on personal financial

circumstances. The overall goal was to gather as

diverse a body of students and faculty as possible.

Students would be chosen on the basis of aca-

demic merit and the breadth of their interests

and commitments.

18

If you build your castles in the air,

your work need not be lost; that is

where they should be. Now put the

foundations under them.

10

— Henry David Thoreau

19

awrence Milas and the board were doing

their homework, compiling their wish list

and talking to as many people in engineering

education and engineering businesses as they

could. On the advice of Jon C. Strauss, president

of Harvey Mudd College, Milas contacted

Richard Miller, dean of engineering at the

University of Iowa, to discuss whether Miller

would be willing to become a candidate for

president of Olin College. Miller’s credentials

spoke to all the issues that Milas was trying to

address at Olin. He had modernized Iowa’s engi-

neering curriculum and facilities, and had created

the nation’s first Technological Entrepreneurship

Certificate Program for engineers. He had the

teaching credentials, the professional reputation

and the innovative temperament that would both

serve the Olin vision and establish its credibility

as an academic enterprise.

Milas’ overtures, however, were not immediately

welcome. Miller had just turned down another

offer to relocate, and he and his family were just

settling back into their routine. But Milas was

persistent — the two men should at least meet

to talk about it. Miller went to meet Milas at his

Florida office to hear what he had to say.

The conversation lasted for the better part of

two days, as Milas laid out his vision of the new

school. Overall, Olin’s educational goals were

consistent with the changes Miller had been

trying to make at Iowa. Two ideas, however, were

especially compelling.The first was that the Olin

Foundation would finance the costs of the proj-

ect, down to tuition stipends that would allow

students to attend virtually for free. Olin’s would

be possibly the only college presidency in the

country for which fundraising was not the highest

priority; rather than being the frontman for

raising money, the president would actually be

able to devote his energies to making the project

work. The second was the idea of continuous

innovation and improvement, a college that

would not fall into the complacency of other

successful schools but instead constantly challenge

itself to improve and take the risks necessary to

maintain innovation. That was an attitude that

Miller had not encountered before in higher

education, and one that he

regarded as a “challenge

worth dedicating your

life to.”

11

Miller went back to Iowa

and wrote out the ideas

that the conversation

inspired; he sent his notes

to Milas. He also remem-

bered that in his previous

position at USC, he had

taught and held offices in

Olin Hall and Vivian Hall

— both the result of Olin Foundation grants —

and that the foundation had a long history of

involvement in engineering education and a

strong reputation for delivering on its commit-

ments. The foundation had the money and had

developed a credible business plan. Miller’s hat

went into the ring.

The Less-Than-Once-in-a-Lifetime Opportunity

Richard K. Miller

L

20

To evaluate possible candidates, the foundation

formed a national search committee consisting

of the four directors and several distinguished

higher education leaders. Milas screened the

candidates and chose the best two or three to

be brought before the committee for interviews.

The committee selected Miller in a unanimous

vote. He took office in February 1999 as the first

employee of Olin College.

With the addition of Miller as president, the

implementation of the foundation’s conceptual

plan accelerated. Miller was tireless in his efforts

to get the college started. His commitment of

time and energy, combined with an intuitive

sense of what was the right course of action for

the college, set a chal-

lenging standard for his

staff. Miller’s leadership

by example was very

effective and inspired

and motivated his staff to

reach extraordinary levels

of accomplishment. In a

short time Miller left no

doubt in the minds of

the foundation’s directors that choosing him as

president was the right decision.

Miller not only embraced the earlier planning,

but also worked with his staff on new strategies

for areas yet to be developed, like faculty hiring,

curriculum development and student recruiting.

He and Milas worked well together, making the

invention phase more successful than might have

been possible without their close consultative

relationship.

Miller’s strong leadership on campus was, at

the least, matched by his being an extremely

effective off-campus spokesman for the college.

Although Miller had expected to focus primarily

on internal busi-

ness in leading

the college, his

ability to com-

municate the

Olin College

story off-campus

became an enor-

mous asset in

gaining almost

instant respect for

the college from important members of the engi-

neering education community and the media.

Miller joined the college not only as the first

employee, but as the first outside member of the

Board of Trustees, which until that point had

consisted of the four directors of the F. W. Olin

Foundation: Lawrence W. Milas,William J.

Schmidt,William B. Horn and William B.

Norden. Over the next few years, the college’s

board would further expand and diversify its

membership.

For the most part, colleges grow incrementally,

adding new functions and structures as the need

arises and trying to retool those that become

obsolete. So, one good part about starting from

scratch, as Olin did, was that everything — the

structures, the equipment, the people — can be

planned exactly the way you want it. The harder

part is that all those decisions have to be made at

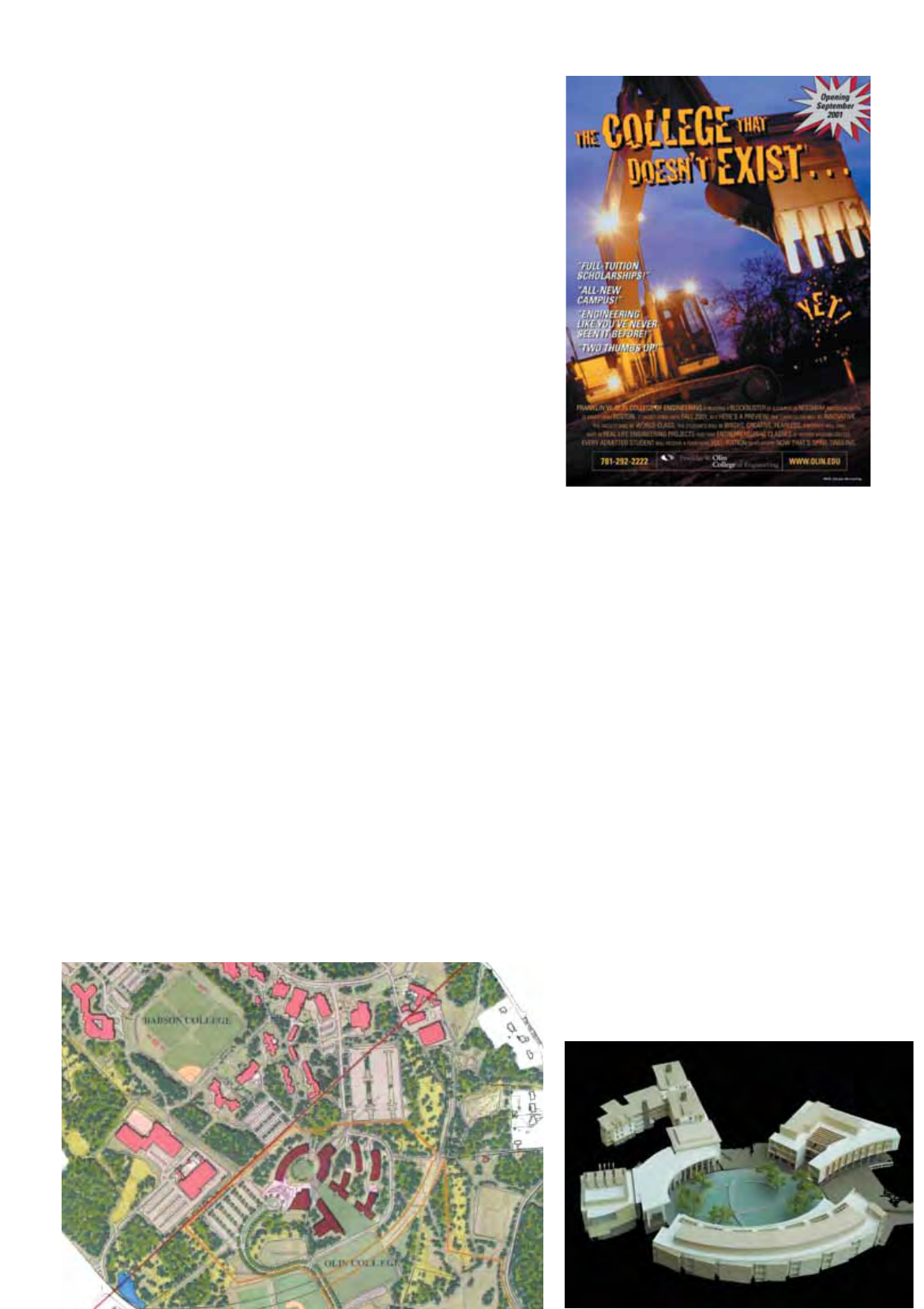

the same time. “The College That Doesn’t Exist

— Yet!” (in the words of an early poster) had to

be planned and guided by the Administration-

That-Didn’t-Exist, the Faculty-That-Didn’t-Exist

had to plan the Curriculum-that-Didn’t-

Exist…and so on.

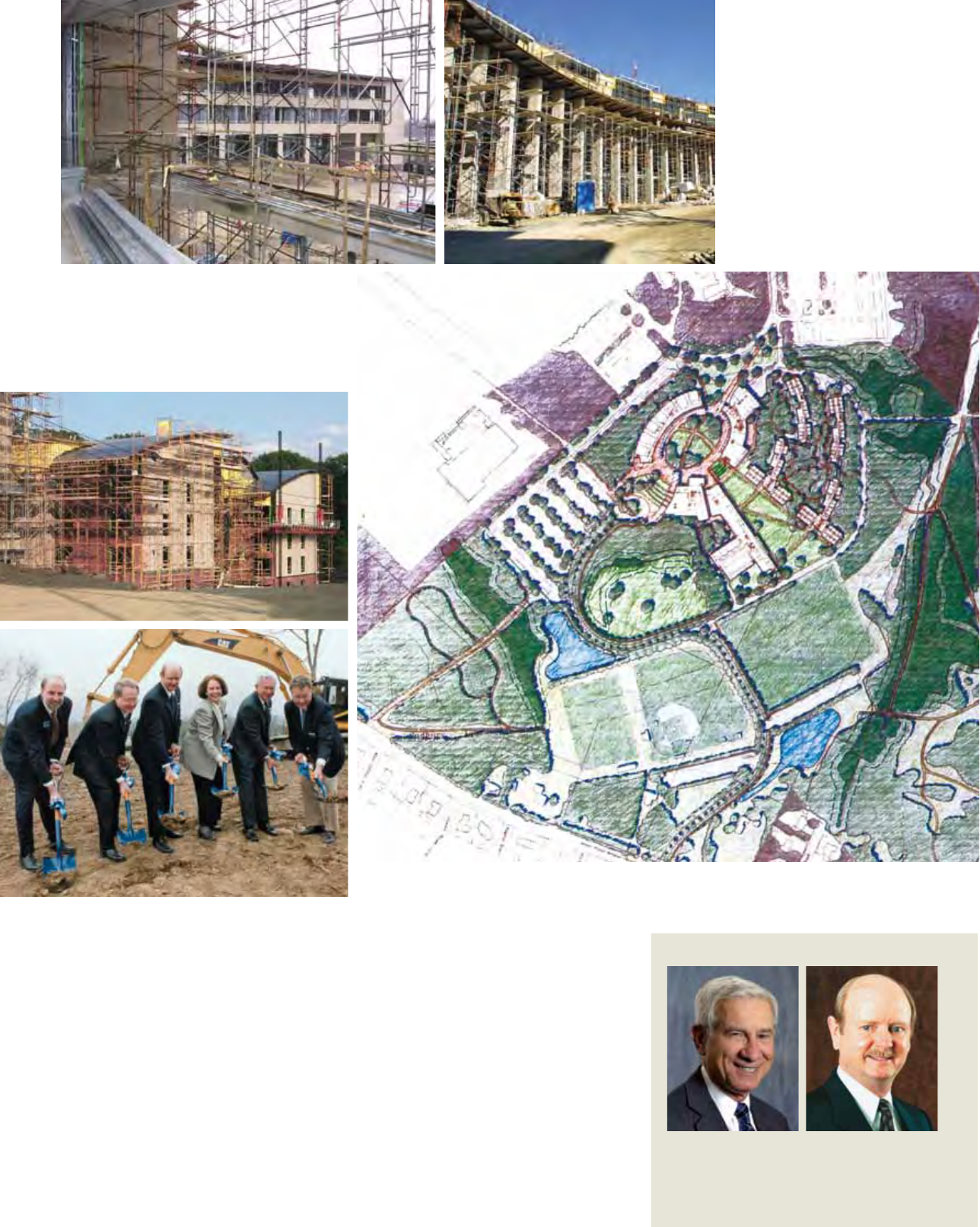

Developing the campus master plan was carried

out by the foundation directors under Milas’

leadership and began before, and ran parallel

Two ideas were especially

compelling: The Olin

Foundation would finance the

costs of the project, down to

tuition stipends that would

allow students to attend

virtually for free. The second

was the idea of continuous

innovation and improvement,

a college that would not fall

into the complacency of other

successful schools.

President Miller became very

adept at explaining Olin to the

media.

with, many of the early founding milestones,

including the receiving the charter and hiring the

first employees. For help in developing the cam-

pus plan, Milas turned to Vanasse Hangen

Brustlin, Inc., real estate acquisition specialists;

Dober, Lidsky, Craig and Associates, facilities

planning consultants; and Perry Dean Rogers

Partners, architects specializing in institutional

and academic structures. A key role in this effort

was played by James Eifert, the Rose-Hulman

educator who also had assisted in the charter

effort. Eifert’s job was to develop a detailed vision

of the academic program for use by the campus

architects in planning buildings. Based on his

own experience as an educator, Eifert’s plan

reflected the innovative approach that he and

Milas had discussed. The plan was later fine-

tuned by the Olin administration and faculty

after they were hired.

To construct the campus, the foundation decided

to purchase the land from Babson College:

70 undeveloped acres adjacent to the Babson

campus on the Needham-Wellesley town line.

It was no accident that Olin came to be located

near Babson. Top ranked in entrepreneurship,

Babson was the perfect partner for the sort of

entrepreneurially minded engineering education

Olin had in mind. Eventually, the two institutions

would come to share faculty, academic centers

and services as part of a wide-ranging collabora-

tion.

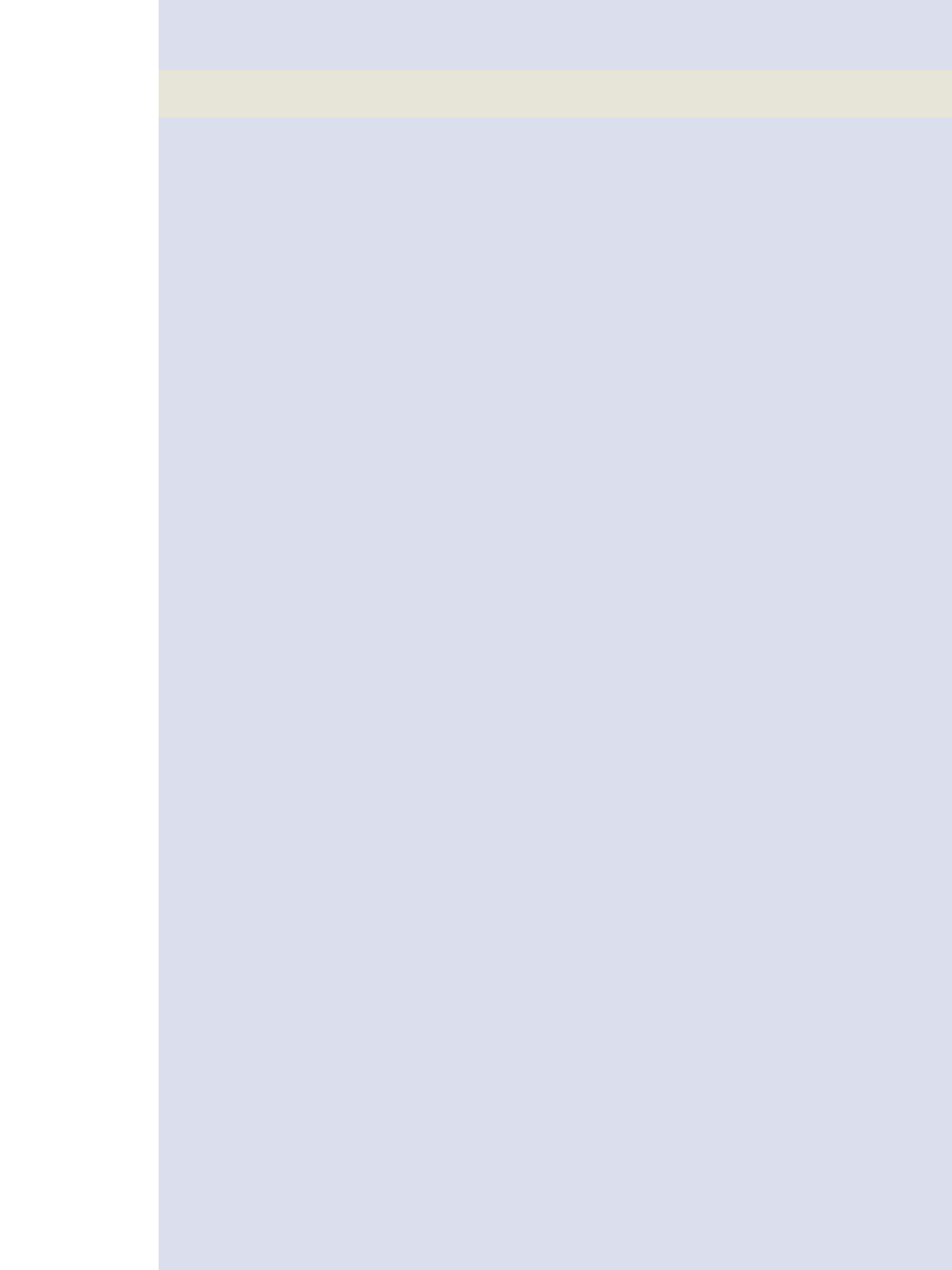

The site Olin purchased from Babson, hilly in

some places and low-lying and boggy in others,

was a tangle of trees and brush. For immediate

use, the college acquired a row of houses right

along the roadway in front of the meadow and

turned them into temporary offices.

Physically, the campus was placed as close to

Babson as possible, with walkways and open

spaces linking the two sites in order to facilitate

connections between the schools. The architects

of Perry Dean Rogers Partners laid out a central

oval — a modern twist on the traditional quad-

rangle — ringed by the campus’ main academic

buildings: the Olin Center, the Campus Center

and the Academic Center. The oval crowns the

topographic high point of the site, and wide

21

This fall 2000 poster was mailed to

high school guidance counselors

nationwide to create awareness.

22

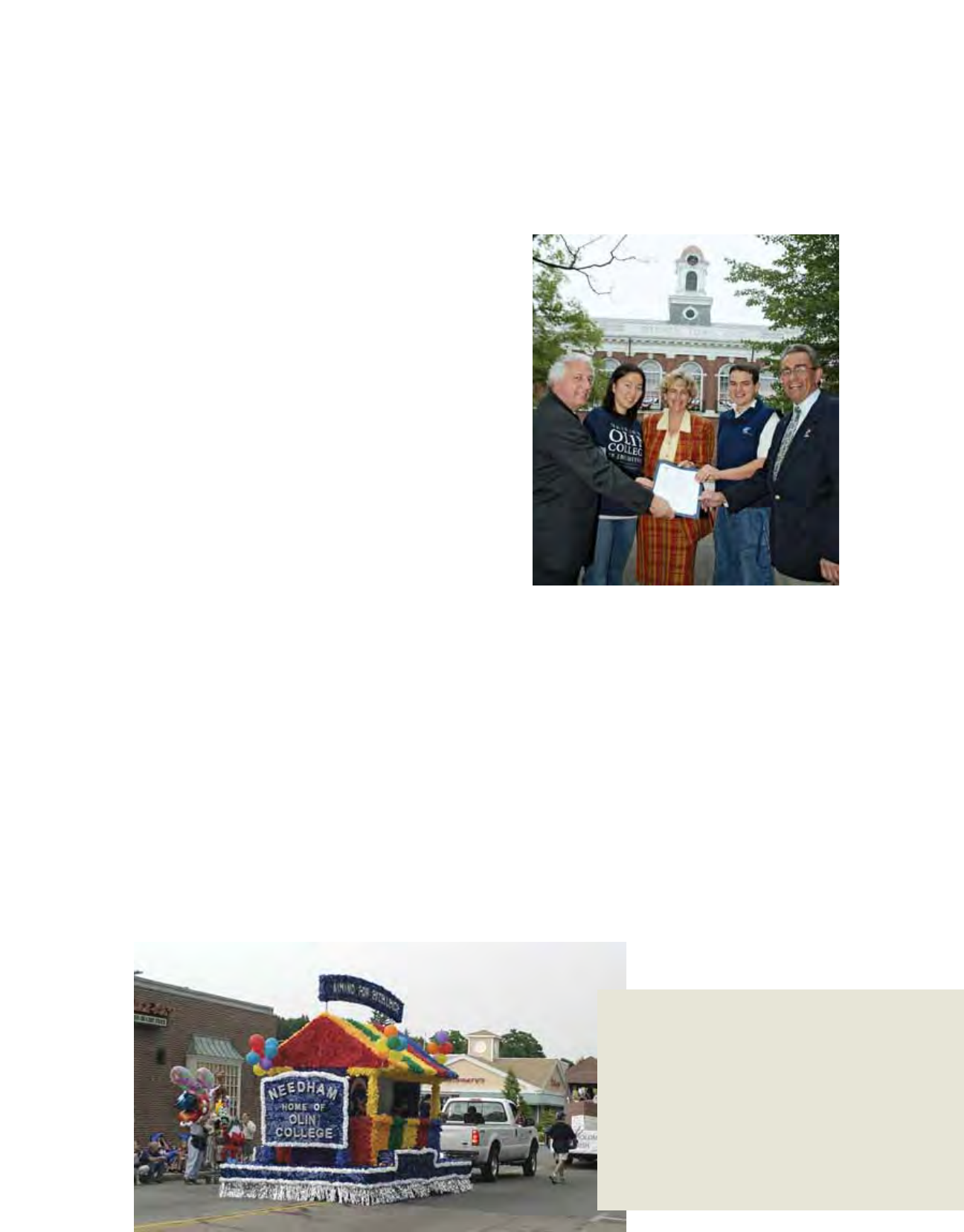

The first phase of Olin campus

construction took place from early

2000 through 2005.

breaks between the encircling structures are filled

with long vistas over the Great Lawn and the

wooded slopes. Glass facades on the interior-facing

walls of the encircling buildings reinforce the role

of the oval as the focal point of the campus.

Inside, the most notable feature was the fluid

arrangement of the faculty offices and labs; rather

than clustering academic specialties together, the

various facilities are interwoven to foster interdis-

ciplinary collaboration and sharing of ideas.

Student dorms were

designed to promote

community as well as

privacy. Although

students enjoy double-

occupancy rooms as well

as suites with private

bedrooms and bathrooms,

inviting communal spaces

furnished with such

amenities as fireplaces,

Olin Foundation President Lawrence Milas

oversaw the early development of the

college and chaired the committee that

hired Richard K. Miller as president.

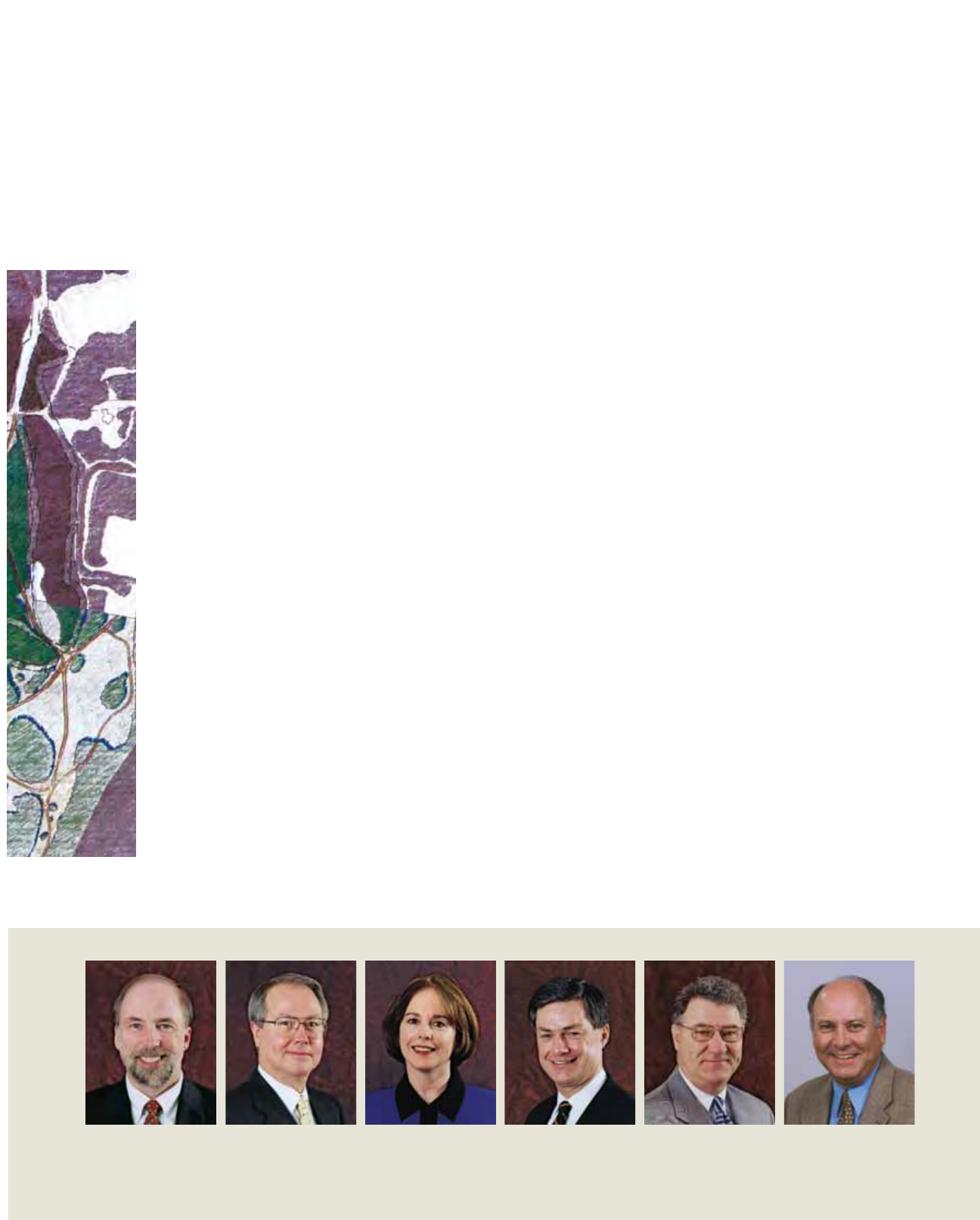

Original Leadership Team

common lounges and very comfortable furniture

provide tempting venues for collaborative work

or socializing. The campus facilities have been

recognized by Princeton Review as among the best

in the nation.

While the campus was being built, Milas and

Miller were assembling their core leadership

team. Stephen Hannabury was hired to be vice

president for administration and finance from

Boston University’s School of Management,

where he had overseen a major construction

effort and maintained strict budgetary control

for 14 years. David Kerns, a widely respected

academic, came over from Vanderbilt to assume

the office of provost.Also from Vanderbilt,

Sherra Kerns was hired as the vice president

for innovation and research, a unique position

that established these priorities at the very top

of the Olin structure. Charles Nolan, legendary

in admissions circles for his management ability,

had only to cross the street from Babson to

become Olin’s first dean of admission, but

Duncan Murdoch, known as one of the most

creative marketers in higher education, had to

cross the country from USC to take the post of

vice president for external relations and enroll-

ment. Roger “Rod” Crafts, a veteran student

life professional, joined Olin from Brandeis

University in August 2000, completing the

Leadership Team in its original configuration.

Like Miller, all were known in their fields for an

innovative, even adventurous, approach to their

work. All were drawn to Olin by the uniqueness

of its vision, and by the “less-than-once-in-a-life-

time” opportunity to use their knowledge and

skills to create something new and effective.

Their formidable professional reputations put the

academic world on notice that Olin College was

a serious enterprise.

Bringing in an equally respected faculty was the

next task, one that fell primarily to Richard

Miller, David Kerns and Sherra Kerns. The ideal

Olin professor would be a gifted teacher, deeply

committed to the classroom and accomplished

in the lab. He or she would be creative, open to

collaboration and willing to teach in new ways.

Above all, faculty members were expected to be

inspirational teachers of undergraduates. The

ideal faculty member would also be committed

to intellectual vitality through scholarly and other

creative endeavors, and would bring this vitality

into the classroom. All faculty members would

be expected to pursue nationally visible achieve-

ments. Moreover, he or she would have a broad

range of interests that extended beyond science

and engineering to history and society, arts and

letters. The wish list was long and comprehen-

sive.

23

Stephen Hannabury David Kerns Sherra Kerns Charles Nolan Duncan Murdoch Roger “Rod” Crafts

VP for Administration Provost VP for Innovation Dean of Admission VP for External Dean of Student Life

and Finance and Research Relations and

Enrollment

While Olin’s new approach posed an exciting

challenge for educators, there were also serious

drawbacks. Most of the potential faculty had not

yet heard of Olin. Also, the college was much

more of a concept than a reality at this point,

and Olin would not offer tenure, nor would it

provide an opportunity to work with Ph.D.

students. Nevertheless, job ads were placed in

the professional journals, and Miller, Kerns and

Kerns went on the road, speaking at professional

conferences and meetings about Olin and its

innovative approach to education.

Clearly, they were persuasive — they received

approximately 1,500 applications for the initial

eight slots that they were trying to fill. Many of

the applicants had academic or professional quali-

fications in the arts and humanities, as well as in

science or engineering, and were searching for an

opportunity that would allow them to integrate

their many interests. Several were attracted, again,

by the rare opportunity to be involved at the

start and to create something new and meaning-

ful.

Olin’s founding faculty arrived in the fall of

2000.

With the selection of the initial administration

and faculty, the implementation process was in

full swing. The blueprint for this process was a

document entitled “Invention 2000,” a two-year

strategic plan that encompassed curriculum

development, student life, administration, market-

ing, finance and governance.

The “discovery” phase of curriculum develop-

ment consumed the new faculty’s first year at

Olin. Faculty teams studied curricula and teach-

ing models at various institutions and visited, or

hosted visits from, more than 50 colleges, busi-

nesses and government agencies. A number of

these outside advisers were also appointed to a

President’s Council to provide ongoing advice.

About midway through the first year, the broader

ideas gathered through consultation coalesced

into the “Bold Goals,” a vision statement of

Olin’s educational ideals, against which all cur-

riculum decisions would be tested. The Bold

Goals for Olin’s curriculum were as follows:

• Hands-on design projects included in the

education plan for every year

• An ambitious and authentic senior capstone

project representative of professional

practice

• Opportunities to work independently, as

team members and as team leaders

• Opportunities to perform before audiences

comprising experts in the field of the presen-

tation or performance

Founding faculty, hired from an initial pool of more than 1,500 applicants:

(from left) Dr. John Bourne, Dr. Daniel Frey, Dr. Diana Dabby, Dr. Lynn Andrea

Stein, Dr. Hillary Berbeco, Dr. Joanne Pratt, Dr. James Propp and Dr. Brian

Storey. Propp left before the Partner Year. Not shown: Dr. Stephen Holt.

Provost David Kerns and VP Sherra Kerns were personal

friends with Paul Penfield, then head of the Electrical

Engineering and Computer Science Department at MIT. In

1999, as they were considering the invitation of President

Miller to join the Olin team, Sherra said to Paul, “It seems

like a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity,” to which Paul

quickly responded, “Oh no, statistically, having the oppor-

tunity to start a college is a much-less-than-once-in-a-

lifetime opportunity.” This statement was a key factor in

the Kerns’ decision to leave Vanderbilt for Olin.

Several years later, when Provost Kerns was recruiting

Dr. Michael Moody to be dean of the faculty, Moody said,

“Well, this must be a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity for

you,” and David Kerns reiterated the statement, “Oh no, it’s

a much-less-than-a-once-in-a-lifetime opportunity.” Dean

Moody later recounted that this was a pivotal factor in his

decision also.

The Less-Than-Once-in-a-Lifetime

Opportunity

25

• An international or inter-

cultural immersion

experience

• A substantial constructive contribution to

society through social responsibility and

philanthropy

• Ability to communicate logically and persua-

sively in written, spoken and visual/graphic

forms

• Self-sufficiency and the ability to articulate

and activate a vision and bring it to fruition

These Bold Goals were bounded by a conceptual

framework that came to be known as the

“Olin Triangle.”At the peak of the Triangle was

Superb Engineering, supported by the Arts,

Humanities and Social Sciences (“AHS”)

(encompassing Design, Creativity and Innovation)

and by Entrepreneurship (including Philanthropy

and Ethics). In order to prevent students’ creative

endeavors from being swept aside by the pressure

of coursework, the first two years of the curricu-

lum incorporated work in the arts and humani-

ties, culminating in an AHS capstone project. In

addition, students were allowed to accumulate

some of their nondegree credits through their

“Passionate Pursuits,” their chosen areas of

artistic/creative interest. The college would offer

scheduled time and faculty and financial support

for the Passionate Pursuits and for the various

organizations that provide services to

the community and the college. Olin’s

educational mission was defined as

preparing well-rounded students able

to use their technological expertise to

shape the future and solve society’s

problems, whether or not they ulti-

mately went on to be engineers.

Beyond the Bold Goals and the dis-

covery of best practices, it was neces-

sary to configure an actual four-year

curriculum, one that would fulfill the

desired educational goals, meet ABET’s

accreditation expectations, and fall within the

practical constraints of time and cost. This task

was entrusted to a subcommittee called the

Curricular Decision-Making Board (CDMB).

The CDMB winnowed out the many options to

come up with a curriculum plan that emphasized

both course work and project experience. In the

following year, curriculum ideas were tested on

the Olin Partners, 30 students who were recruit-

ed to spend a special pre-enrollment year assisting

in the development of the college’s programs.

Partners took part in the ongoing CDMB, and

then tested curriculum ideas as four-week “mod-

ules.” Successes and failures were evaluated, and

the changes were built into the growing

curriculum plan. The final product was based

on a two-year foundation of course and project

work, a third year of specialization in which the

student focuses on a particular area of interest

and a fourth year (realization) during which the

expertise is applied to a project of professional

caliber.

Differing from the traditional engineering cur-

riculum, projects form a significant percentage of

the student’s learning plan from the start (a strat-

egy known at Olin as “do-learn” — that is,

learning by doing); the percentage of project

In February 2001, Provost David Kerns

arranged a retreat at the Warren

Conference Center in Ashland, Mass., for

the founding faculty to consider the Olin

curriculum and other academic matters.

After dinner on the first day, without any

agreed-upon schedule or plan, faculty

members began assembling in the

downstairs meeting room, where they

had discussed wide-ranging issues all

day; eventually, everyone was there.

Picking up a marker and standing before

Bold Steps: How the “Bold Goals” Came into Being

a white board, VP Sherra Kerns said, “OK,

without defining the curriculum in detail

at this point, let’s list the things we have

come to agree upon.” By the end of the

evening, the group had articulated the

“Bold Goals,” which would feature

prominently in virtually every discussion

about Olin’s curriculum for the next

several years.

SUPERB ENGINEERING

ENTREPRENEURSHIP

ARTS, HUMANITIES

and SOCIAL SCIENCES

work increases in importance over the

four years. In the first two years, projects

are structured around integrated course

blocks (ICBs), large course blocks that

combine two areas of study (say, engi-

neering and biology) and an interdisci-

plinary project. The ICB model empha-

sizes the interdisciplinary nature of Olin’s

teaching and provides teamwork opportunities

for both faculty and students. Another distinctive

feature of the curriculum is the design stream,

which provides coursework in engineering

design continuously throughout the curriculum.

The fourth-year senior capstone project (later

known as SCOPE), pairs student teams with

businesses to develop a solution that incorporates

the students’ specialized skills and meets the

business clients’ requirements and schedules. Thus

at the end of four years, students not only learn

the fundamentals of engineering science, but also

can apply these techniques to the solution of

real-world problems. Another unusual curricular

element, Olin Self-Study, provides opportunities

for independent research and lifelong learning.

While the individual elements of the curriculum

continued to morph over the first few years,

undergoing tweaks and name changes, its basic

structure has remained remarkably close to the

original vision.

26

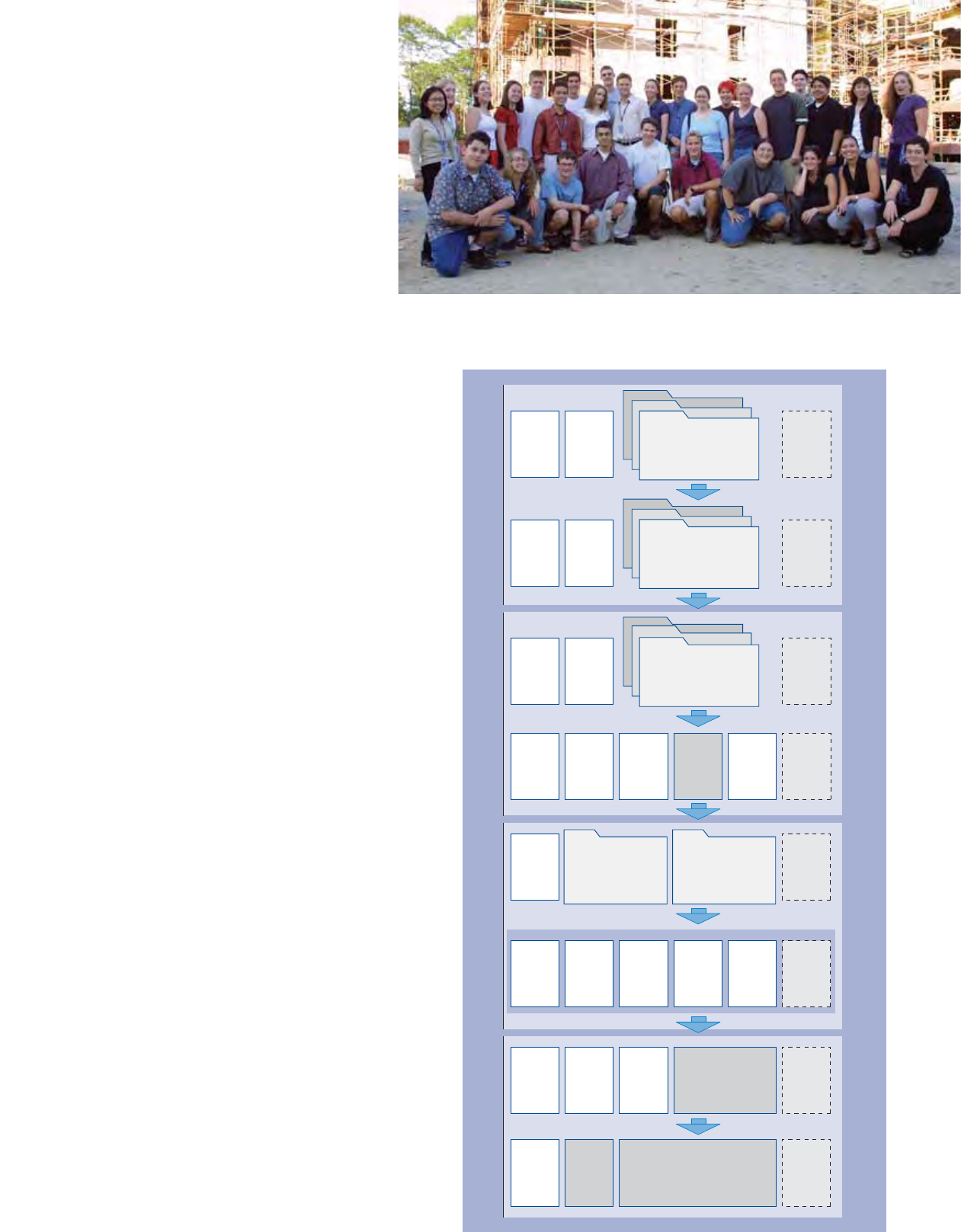

The Olin Partners arrived in Needham in August 2001 and lived in a temporary

modular residence hall while the campus was being built.

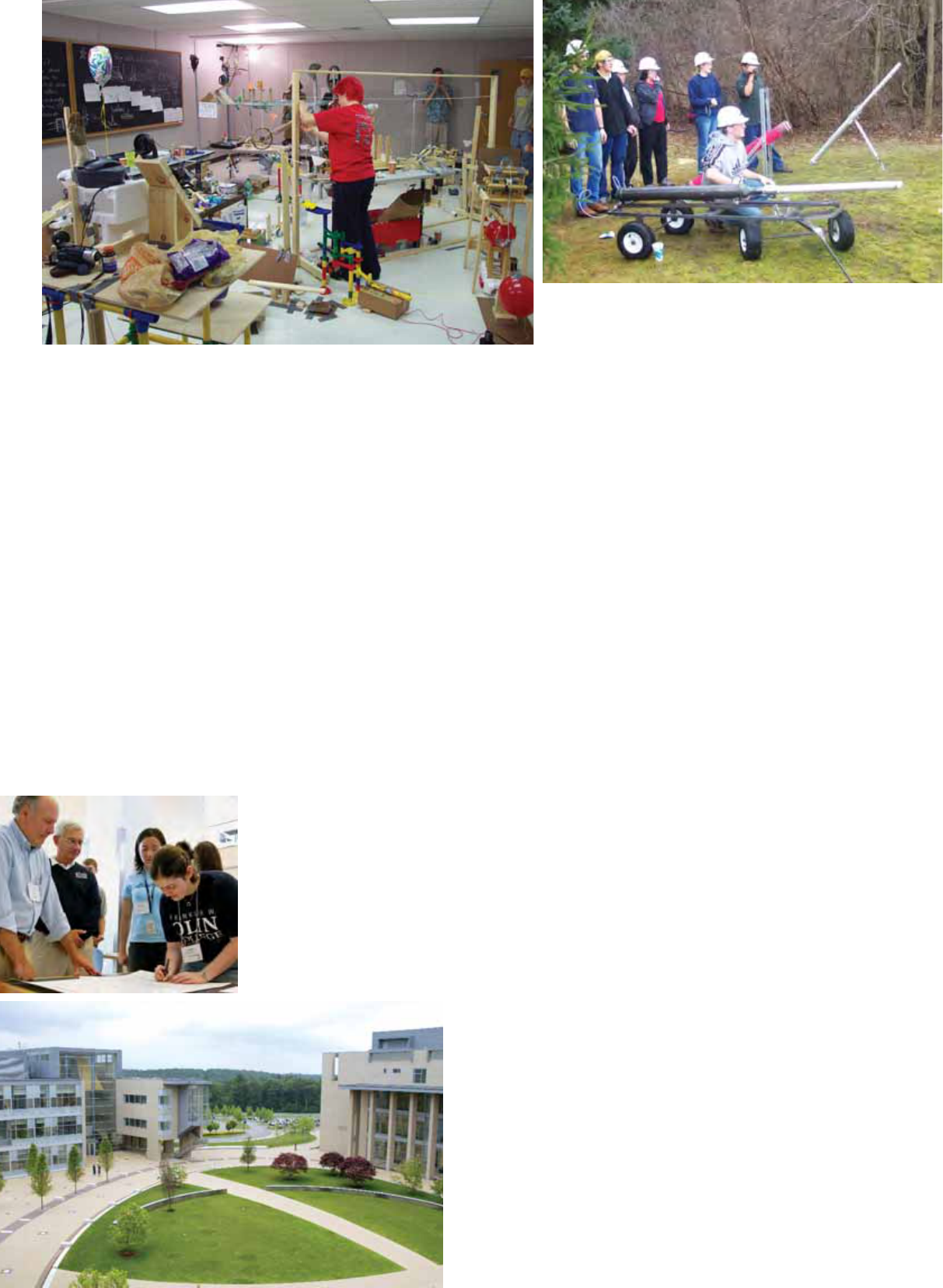

One of the earliest published

versions of the Olin curriculum.

Arts,

Humanities

and

Social

Sciences

4

Arts,

Humanities

and

Social

Sciences

5

Technical

Elective

1

Technical

Elective

2

Free

Elective

3

Free

Elective

4

Arts,

Humanities

and

Social

Sciences

6

Technical

Elective

3

Advanced

Math

Senior

Capstone

Arts,

Humanities

and

Social

Sciences

7

Arts,

Humanities

and

Social

Sciences

Capstone

Passionate

Pursuits

(optional)

Passionate

Pursuits

(optional)

Passionate

Pursuits

(optional)

Passionate

Pursuits

(optional)

YEAR 3YEAR 4

Integrated Course Block:

Engineering Core 1

• Class

• Project

Integrated Course Block:

Engineering Core 2

• Class

• Project

Senior

Capstone

POSSIBLY AWAY

Arts,

Humanities

and

Social

Sciences

1

Introduction

to

Modeling

and

Control

Arts,

Humanities

and

Social

Sciences

2

Free

Elective

1

Arts,

Humanities

and

Social

Sciences

3

Signals

and

Systems

Applied

Mathematical

Methods

Free

Elective

2

Software

or

Systems

or

Thermo

Sophmore

Design

Project

Biology Passionate

Pursuits

(optional)

Passionate

Pursuits

(optional)

Passionate

Pursuits

(optional)

Passionate

Pursuits

(optional)

YEAR 1YEAR 2

Option 3

Option 2

Option 1

Integrated Course Block:

• Mathematics (calculus, diff. eq’s.)

• Physics (mechanics, thermo)

• Design Project

Option 3

Option 2

Option 1

Integrated Course Block:

• Mathematics (vector calculus,

linear algebra)

• Physics (E&M, circuits)

• Design Project

Option 3

Option 2

Option 1

Integrated Course Block:

• Materials Science

• Business Basics

• Design Project

27

he Olin Web site does not sell little pink and

blue bibs that say “Olin Class of ??” It may

come to that someday, but we’re not there today.

Yet the “bib gap” represented a serious challenge

for the Olin admission staff. Given the stiff com-

petition for top-tier students and the undeniable

attraction of a prestigious college name, how

could Olin, with its still-unproven newness, get

itself noticed?

From the outset, the admission staff crafted a

two-pronged strategy designed to appeal to both

the exuberance of 18-year-olds and the caution

of

their parents. For the prospective students, Olin

mailings were all attitude and jarring colors.They

featured bungee jumpers (“Fearless?”) and huge

growling excavators. They played off the exclu-

sivity of established schools by posturing with a

mock exclusivity of their own: “There’s only one

thing cooler than getting into Harvard, MIT and

Stanford — TURNING THEM DOWN!” One

of the first admission pieces, “7 Reasons You

Should Apply to an Engineering College That

Doesn’t Exist,” was a card fan anchored at the

corner by an aluminum rivet and mailed in a sil-

ver Mylar envelope. The prospectus was bound

with silver duct tape. These brochures were

meant to attract notice, not be tossed out with

the junk mail.

The appeal to parents was more direct and hard-